“When France sneezes, Europe catches cold.”

- Clemens von Metternich

Paris is a city of revolution and reaction. As anyone who keeps at least a passing eye on the news will see whenever Paris is mentioned. We who live here have to deal with protests and strikes on a nearly daily basis, but this is also what makes Paris such an interesting place to live. It is a city of great culture, food, art, architecture, and fashion, but it is also a city of ideas. These revolutions, some failed and some successful, have marked the city in sometimes surprising ways.

Living in Paris for the last decade, I have seen how revolutions have shaped the city. When you visit the newly restored Notre Dame, remember that its history has been shaped by revolutions and rebellions. The Louvre became a museum under revolutionaries, and as you walk through the streets, keep an eye on the walls. You can see graffiti that can give you a little insight into Paris's revolutionary present. Civil unrest is part of the story here, and any self-respecting tour guide should be able to bring that alive.

As a self-respecting tour guide, I feel it is my duty to give you a little overview of that past. Here, you can take a quick walk through Le Marais, one of the most energetic and beautiful parts of the city. Revolutionary vestiges can still be found around the city, and this article is designed to inspire the interested to explore a little bit deeper below the surface than the baguettes and boulevards. To get an idea of what really makes Paris tick.

An aristocratic coat of arms carved off during the Revolution at the Hotel de Beauvais

The French Revolution! The Guillotine and the Bastille. Marie Antoinette is telling people to eat cake (she never said this, but it's a good line regardless). These are things that most visitors to Paris will have at least a passing knowledge of. However, the forces that the French Revolution of 1789-99 unleashed would spend the nineteenth century battling it out in Paris. Numerous rebellions have marked the city since.

The French Revolution lives in the imagination but also still in the streets of the city. If, as a visitor, you happen to be using the metro system (the best way to get around), and happen to be on line 5 metro at the Bastille stop, pay attention to the platform. On one side of the platform sits one of the only remaining parts of the Bastille prison to survive the French Revolution. Large parts of it were turned down and used to build things like the bridge connecting the Place de la Concorde to the Assemblé Nationale. Other bits were taken away and used as souvenirs and sent all over the world.

One of the only remaining bits of the Bastille prison, inside a metro station!

Nowadays, the remnants of the Bastille serve as a place for people to sit while waiting for their metro, or in the case of the photo, a place to leave your baguette; for what reason, I do not know. I am going to presume it is a patriotic gesture rather than a forgotten sandwich.

Following the rise of Napoleon and his subsequent defeat at Waterloo (by a fellow Irishman, no big deal…), the brothers of Louis XVI were placed back on the throne by the victorious great powers of Europe. The incredibly fat Louis XVIII and his brother, the incredibly reactionary and conservative Charles X, ruled France until 1830. Charles X himself was deposed in yet another rebellion in 1830.

We can see some vestiges of this rebellion by wandering around the Marais in Paris. Take a walk down towards the banks of the Seine to the very impressive Hotel de Séns, once home to a Bishop, a jam factory, and now a library dedicated to fashion. On the eastern facade of the building, above the main entrance, a small cannonball can be seen stuck into the wall. This cannonball was fired in fighting in the neighborhood on the 28th of July, 1830. It is a pretty small cannonball, though I suppose that is all relative, you wouldn't want it hitting you.

A cannonball lodged into the wall at the Hotel de Sens

By the way, after Charles X was deposed, his cousin Louis-Philippe came along as the last king of France, ruling a constitutional monarchy. Not that this stopped people from rebelling against him in 1832, failing this time however. This rebellion was immortalised by Victor Hugo and in more modern times by Claude-Michel Schönberg, and Alain Boublil. The writers of Les Miserables and the fantastic musical, respectively. The 1832 rebellion is the one where we find Jean Valjean and compatriots building barricades and singing their way to freedom.

Louis-Philippe's reign ended in 1848, a year of revolution all over Europe, and eventually gave way to the Bonaparte family's return under Napoleon's nephew, Napoleon III. Napoleon III reshaped the city of Paris with its grand boulevards under his city planner, Eugene Haussmann. Haussmann, however, compulsorily purchased the land to build his new boulevards and opera houses. Many of the poor who had traditionally lived in the city center were forced to move to the outskirts of Paris. This changed the city aesthetically and socially.

Montmartre, Belleville, and the Butte Aux Cailles became the most working-class and revolutionary parts of the city. Eventually, Napoleon III lost the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 and was forced into exile, so rebellion began against the new French Republic. Massively violent and impactful, this rebellion became known as the Commune.

A mix of different people, from anarchists to liberal intellectuals, set up self-governing communities throughout the city. Some parts of the city still hold the scars of those days. In fact, on visiting the immense Louvre, it might surprise you to know that the building used to be even bigger than it is right now. One entire wing, the Tuileries Palace, was destroyed during the Commune. Eventually, in what became known as the Bloody Week, 21-28 May 1871, up to 20,000 people were killed in fighting as the community was repressed.

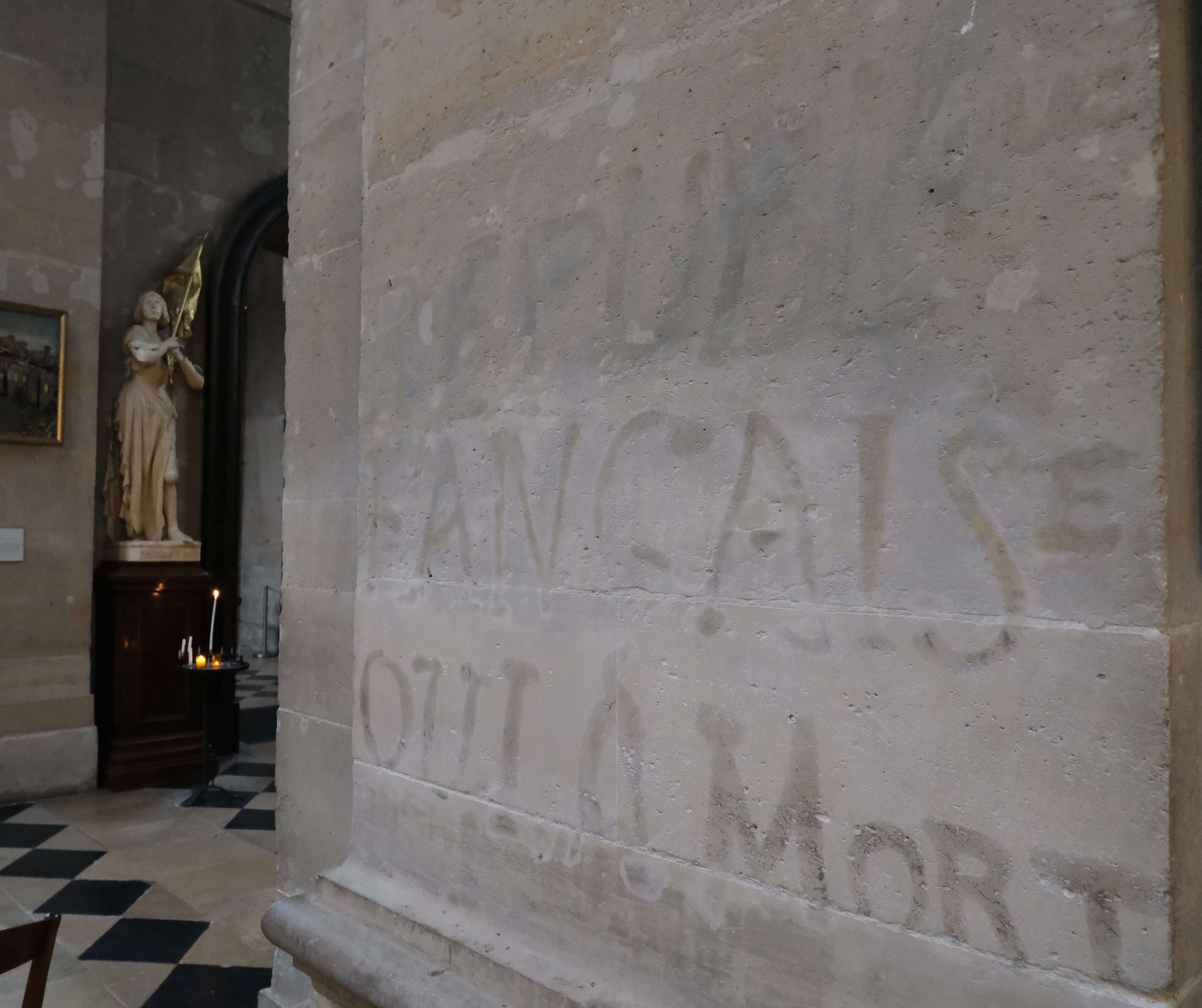

Revolutionary Graffiti from the Commune in Saint Louis Saint Paul church

If you go and visit the beautiful Jesuit-built Baroque church of Saint Louis Saint Paul, right in the heart of the Marais, you can find some graffiti from the commune. It is a small vestige of a time when the Marais was a self-governing municipality. The graffiti was daubed on one side wall, missed at first, and then corrected. Someone tried to steal it off at some point but didn't manage to finish the job. It sits with a statue of Joan of Arc right beside it, Paris history side by side, in the same church.

When you leave, keep an eye out for the fonts at the door! They are shells from French Polynesia, gifted to the church by one Mr Victor Hugo in honor of his daughter's marriage in the church. He lived around the corner in the Place des Vosges. Also, at the end of Les Miserables, a wedding takes place, and it takes place in that church where, eventually, the communards would proclaim their short-lived republic.

As you leave the church, feel free to break out into song and make Jean Valjean proud.

“Do you hear the people sing?

Singing a song of angry men?

It is the music of a people

Who will not be slaves again

When the beating of your heart

Echoes the beating of the drums

There is a life about to start

When tomorrow comes.”

-Les Miserables