Did you know that in addition to the unmissable masterpieces of Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel, Raphael in the Raphael Rooms, and all the other artistic treasures that make the Vatican so justly famous, the Museum also boasts one of the world’s finest art galleries?

Hidden away in a quiet corner of the Museums, many visitors pass by the Vatican Pinacoteca without giving it a second glance. But with masterpieces ranging from the pioneering work of Giotto that helped usher in the Italian Renaissance, Raphael’s last painting, the only Leonardo in Rome, a stunning Caravaggio, and much much more, for us, the Vatican Museum’s Picture Gallery is a must-visit on any trip to the Museums. To give you a sense of what to look out for on your next trip to the Vatican, we’ve compiled our ten favorite artworks in the Vatican Pinacoteca. Don’t forget that Through Eternity also offers award-winning tours of the Vatican Museums led by an expert guide.

1. Giotto di Bondone Stefaneschi Triptych, c1313-1320

One of the most significant works of the late Gothic period, the pioneering Giotto’s Stefaneschi triptych, was commissioned by the cardinal Jacopo Caetani degli Stefaneschi for the prominent Canon’s altar in Old St. Peter’s Basilica around 1313. Just a few years before, the Papacy had relocated from Rome to Avignon, and Stefaneschi’s donation to the now-reduced Roman church was a powerful plea for the continued relevance of the faith’s traditional home.

On the front of the dual-sided altarpiece, at the center, Christ is seated on his eternal throne surrounded by angels. To the left and right of the central panel, we see the martyrdoms of Rome’s twin patron saints, Peter and Paul - the former crucified upside down in Nero’s circus, the latter decapitated in the countryside to the south of the city. The rear of the altarpiece shows St. Peter in happier times, seated on his papal throne, clutching the keys to the church as Cardinal Stefaneschi himself kneels before him, proffering a miniature version of the altarpiece. A laundry list of saints and holy luminaries complete the ensemble in the predella panels below.

2. Benozzo Gozzoli, Madonna of the Girdle, c1450

One of the early Renaissance’s most popular but now sadly under-appreciated masters, Benozzo Gozzoli was so beloved of the Medici court that he was tasked with decorating their sumptuous palace in downtown Florence. His Procession of the Magi is one of the great delights of the quattrocento, but there is scarcely a town in Tuscany or Umbria that has not been graced by his prolific lyrical genius.

The Madonna of the Girdle was one such commission, painted for the church of San Fortunato in the Umbrian town of Montefalco around 1450. The Madonna hands down to girdle from her seat in heaven to the ever-sceptical St Thomas in the terrestrial realm below, material proof that she had bodily ascended into the celestial sphere. The elegant faces, delicate contouring, and stunning glittering gold leaf all provide a beautiful testament to Gozzoli’s skill.

3. Melozzo da Forli - Sixtus IV appoints Bartolomeo Platina Prefect of the Vatican Library, c1477

Not all of the finest paintings in the Vatican Pinacoteca are strictly religious in nature. An absolute masterpiece of probing psychological portraiture, Melozzo da Forli’s depiction of the moment Pope Sixtus IV appointed Bartolomeo Platina to the position of the newly founded Vatican Library’s first Prefect is one of the most vivid windows into the refined world of the Papal Renaissance court in existence. The heavily jowled Pope is seated on the far right, as the humanist Platina, kneeling before him, is poised to receive the official confirmation of his commission.

Platina points downwards out of the painting’s narrative space towards a fictively inscribed text composed by him to exalt the achievements of his new boss, whilst the pope’s fabulously attired cardinal and lay, nephews, look solemnly on - Girolamo Riario and Giovanni della Rovere are in their secular furs and chains behind Platina, whilst the apostolic pronotary Raffaele Riario stands next to future pope and Michelangelo patron Julius II behind the Pope. Melozzo had come to Rome in 1475 and quickly established himself as the city’s pre-eminent painter - this probing multi-figure portrait makes it clear why. To see more of Melozzo’s marvelous work in Rome, check out the spectacular but little-known Bessarion Chapel.

4. Leonardo da Vinci, St Jerome in the Wilderness, c1482

The Vatican Pinacoteca is home to the only painting by Leonardo da Vinci in Rome, a ghostly unfinished rendering of St. Jerome in the Wilderness. One of the most mysterious works from the hand of the great master, little is known about its original function, destination, patron or provenance. The first recorded mention of the work only dates from 1807, when the painting was mentioned in the will of celebrated Swiss Neoclassical painter Angelica Kauffman.

Leonardo’s enigmatic masterpiece once again disappeared without trace after the execution of Kauffman’s will, only to be rediscovered 20 years later by Napoleon’s uncle, Cardinal Joseph Fesch, being used as a workbench by a Roman cobbler. The rescued work was installed in the Vatican in the 1850s. Probably painted in the 1480s, the picture is painted on a walnut panel and portrays the grief-stricken saint alone in a blasted desert landscape poised to beat himself in his already bleeding chest with a rock clasped in his right hand as his faithful lion companion watches his master’s penitence. The preliminary underdrawing is visible throughout, offering a fascinating insight into Leonardo’s working practice and his preoccupation with building up convincing and detailed human anatomies.

5. Raphael, Madonna of Foligno, 1511-12

A stunning example of the sweet beauty for which the Renaissance master Raphael was so admired by his contemporaries, the Madonna of Foligno portrays a celestial vision of a beautiful Virgin Mary clutching a plump and fleshy infant Christ seated on a bank of clouds. Below, Saint John the Baptist and St Francis of Assisi gesture up to the Holy Family, whilst St. Jerome is introducing the patron of the painting, the learned humanist scholar Sigismondo de' Conti, to Mary.

The somewhat gaunt Conti was Pope Julius II’s chamberlain, and he commissioned the painting to offer thanks for his house in Foligno being spared from destruction in a devastating lightning storm. The event is depicted in the background, where a flaming meteorite hurtles towards the city of Foligno. A rainbow arcing over the town indicates the tale’s happy resolution. Note the angel holding a blank plaque in the foreground: the plaque was to bear a personally composed message of thanksgiving to the Virgin, but unfortunately Sigismondo died before he had the chance to put pen to paper.

6. Raphael, The Transfiguration of Christ, 1520

The last work that Raphael was destined to paint in his illustrious but tragically short career is considered by many to be his finest. Commissioned by Giulio de’Medici – the future Pope Clement VII - the massive altarpiece was intended to adorn the cathedral of Narbonne in France, where Giulio was archbishop. The subject matter is a rather ambiguous moment in the New Testament where Jesus has gone with his disciples to pray on a mountainside.

The Messiah is suddenly surrounded by a halo of blinding white light and levitates heavenward along with the apparitions of Moses and Elijah, as a voice from the sky greets him as the son of God. In order to depict this fundamentally abstract miracle, Raphael resorts to a virtuoso harnessing of the power of light – we can almost feel the blinding celestial rays that light up the mountain top, knocking over Peter, James and John with their superhuman force. Raphael in fact combines the events of the Transfiguration with the subsequent Gospel narrative, when Christ’s apostles struggle in vain to cure a young boy possessed by demons – the boy would have to wait for Jesus’ return from the mountain to be successfully exorcised.

A masterpiece both of composition and coloring, the contrast between the celestial world of divine revelation, suffused with blinding white light, and that of the terrestrial world where extraordinarily realistic figures gesture from the miracle of Christ’s Transfiguration to that of the exorcised boy, shows Raphael as the master of both artistic registers.

When the raging fever that carried Raphael to his grave struck the painter, the Transfiguration was all but finished. According to legend it stood at the foot of his deathbed as Raphael’s condition worsened, silent last will and testament to the man that would be hailed as the “God of Art” on his demise. After his death, the painting was displayed for six days in the Vatican, where it caused a sensation. Any thoughts of sending it to France were put on permanent hold: The Transfiguration was first sent to the church of San Pietro in Montorio before finding its way back to the Vatican, where you can still see it today in pride of place in the Pinacoteca.

For many it remains his definitive masterpiece, a vivid sign of the irreparable loss suffered by the world of art on April 6, 1520. With the death of Raphael, so most stories of art go, came the death of the Renaissance itself.

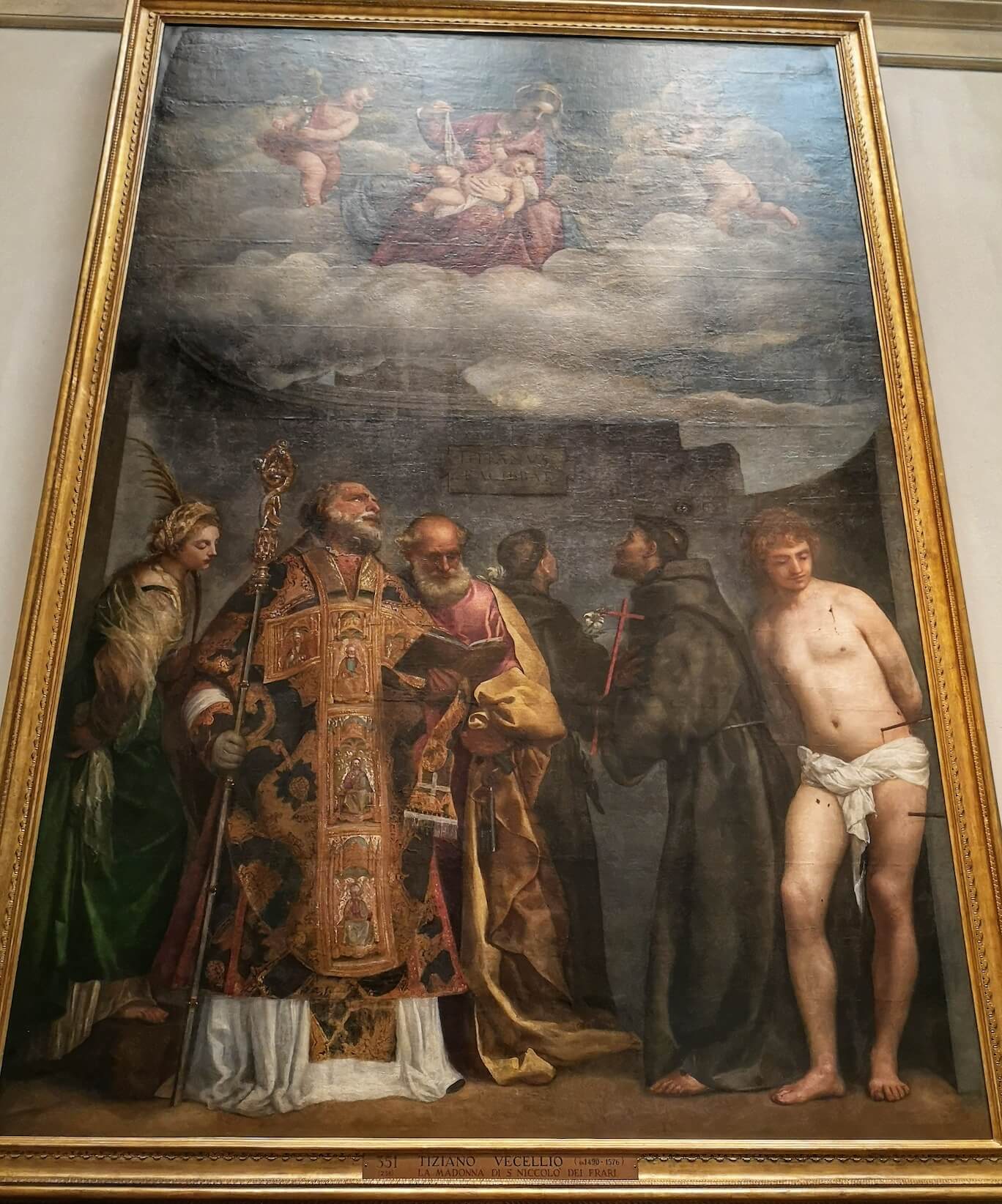

7. Titian, Madonna and Child with Saints, 1535

The greatest and most influential practitioner of the Venetian school during the Renaissance, Titian’s works are characterized by magnificently vibrant coloring and expressive brushwork - the Vatican Museum’s canvas is a bonafide masterpiece of the master’s maturity and depicts the Virgin Mary cradling the infant Christ in a visionary landscape of featherlight clouds surrounded by putti. In the hazy terrestrial world below, saints Catherine, Nicholas, Peter, Anthony, Francis, and Sebastian direct themselves devotedly to the sacred vision. Note the nearly naked Sebastian on the left, pierced through by arrows in reference to his botched execution. The painting was commissioned for the Venetian church of San Niccolò dei Frari before being brought to Rome in the 1770s.

8. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Entombment of Christ, c1600

A true artistic one-off, perhaps nobody captured the seismic shifts taking place in the world of art at the end of the 16th century more than Caravaggio. During his brief but extraordinarily productive career, the impetuous and unpredictable Lombard painter left a string of masterpieces across the Eternal City. One of the finest is the Entombment of Christ he painted for the Oratorian mother church known as the Chiesa Nuova and now in the Vatican Pinacoteca, a startling statement of the artist’s revolutionary style that marked such a break with the ideals of the Renaissance.

Instead of the heroic Christ familiar from countless Renaissance canvasses, Caravaggio offers us up a fleshy corpse. The elderly Nicodemus struggles mightily to support his dead weight, hunched-back doubled over in exertion. His dirty bare feet and age-lined face represent Caravaggio’s commitment to realism. For contemporaries used to the idealised images that flowed from the brushes of artists such as Raphael, the fact that this holy figure looked just like any impoverished old man you might see shuffling along the Roman streets was a shocking confrontation. Behind him, three women express different kinds of mourning: one raises her hands to the sky in grief, another tenderly dries tearful eyes, whilst the Virgin Mary simply stares with burning intensity at her son’s lifeless body. Caravaggio’s vision reflected a new kind of popular spirituality that sought to bring the world of God into direct contact with the everyday, and was wildly popular despite the controversy he courted (murder was merely the culmination of his mile-long police record). The spotlit figures loom dramatically out of the inky-black space of the tomb, an incredible example of the extreme chiaroscuro that made Caravaggio’s work so spectacular and that would come to define the age of the Baroque.

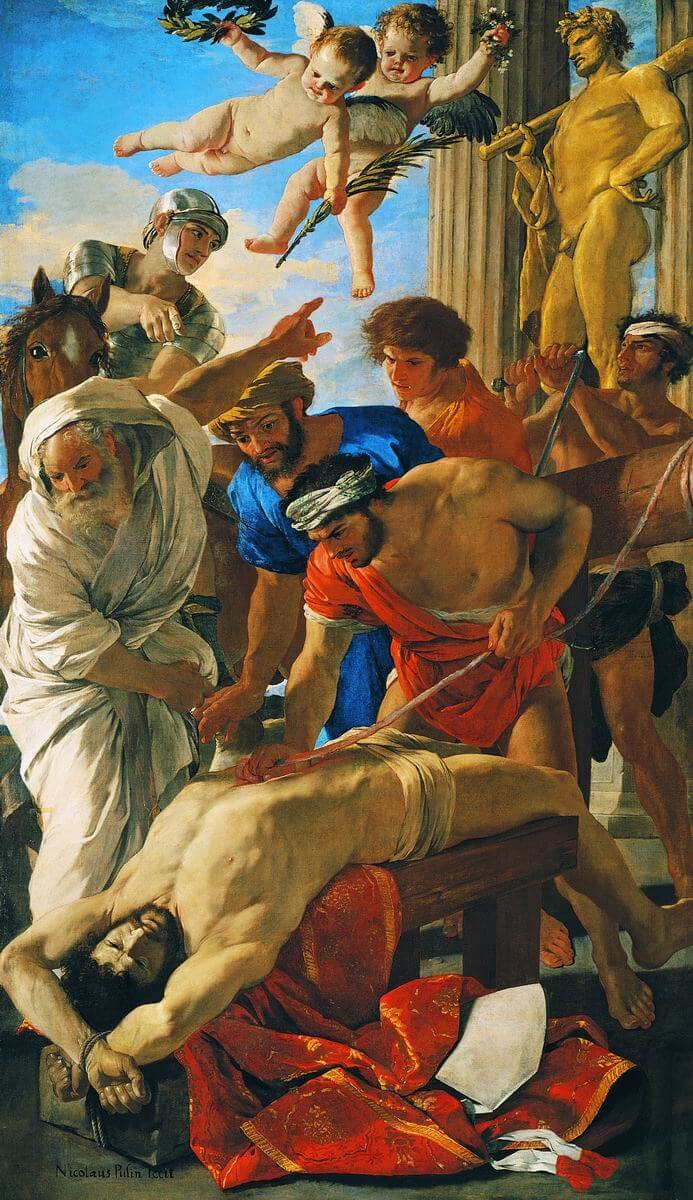

9. Nicolas Poussin, The Martyrdom of St. Erasmus

Martyrdom is by its nature a fairly gory business, but few paintings take such delight in reproducing the wince-inducing details of corporeal desecration than Poussin’s Martyrdom of St. Erasmus, an early-Christian bishop martyred on the orders of Diocletian in 303 AD. Completely out of synch with the remainder of Poussin’s oeuvre, which is characterised by learned and sober takes on the lost world of antiquity, this was the French painter’s first major commission in Rome after arriving in the Eternal City in 1624, and was destined for an altar in St. Peter’s. The unfortunate saint is splayed out on a wooden bench, his torso split open down the middle as a scantily clad torturer yanks out his entrails and spools them around a windlass behind him. Another executioner operates the windlass, turning a crankshaft to draw the poor saint’s innards out further. Pagan priests and soldiers point mockingly to a golden statue of Hercules that the saint had refused to worship, but Erasmus has only eyes for his heavenly reward - emblematised by the descending angels carrying down a palm of martyrdom and crown of sanctity.

10. Domenichino, The Last Communion of St. Jerome, 1614

A narrative tour de force of the final, gasping moments of the superannuated St. Jerome, the Baroque master Domenichino considered this painting to be his masterpiece. In the soaring architectural surroundings of a Roman basilica, the expiring Church father is held up by assistants in order to enable him to take the holy host of his last communion as angels hover in the sky above ready to transport his departing soul to heaven. Though much admired by contemporaries and quickly regarded as one of the city’s great modern works, Domenichino’s Last Communion was not without controversy. The Bolognese painter’s compatriot and rival Lanfranco whipped up a storm by accusing his former colleague of plagiarism, alleging that Domenichino’s canvas was a rip-off of Agostino Carracci’s version of the same rare subject painted 20 years earlier. Although the works share undeniable affinities, other artists quickly jumped to Domenichino’s defence, and it seems that Lanfranco’s motives were far from pure - both artists were at the time competing for the same commission in San Andrea delle Valle, and Lanfranco saw an opportunity to discredit his rival. Whilst the plagiarism affair did little to dim Domenichino’s fame, the accusation was to periodically dog Domenichino for the rest of his career.

Read More Great Content From Our Blog

- How to visit the Colosseum in 2024: Tickets, Hours, and More

- 7 Things you Need to Know About the Trevi Fountain

- Visiting the Vatican Museums and St. Peter's Basilica: The Complete Guide

- 9 Things You Need to Know About the Pantheon in Rome

- 5 Reasons to Explore Italy with Through Eternity

- The Best Catacombs to Visit in Rome

- A tribute to the art of sculpture: the treasures of the Octagonal Courtyard at the Vatican Museums

- The Devil is in the Details: Hidden Secrets of the Vatican Museums

- Laocoon sculpture in the Vatican Museums

- The Resurrection of Christ in Vatican Museum's Tapestry Gallery