An artwork should be fertile. It must give birth to a world.

- Joan Miró

No history of modern art can be written without devoting a chapter to Joan Miró. A pioneering genius whose work spanned the first seven decades of the century, Miró made signal contributions to a wide variety of artistic styles and genres, ranging from Surrealist and Abstract expressionist painting to Dadaist sculpture, ceramics, tapestries and massive public monuments. Freely mixing media, genre and tone, Miro’s sometimes serious, sometimes playful oeuvre paid scant regard to canonical ideas about the arts or current trends, and in their dreamlike lyricism, bold colours and organic forms frequently broke with traditional artistic conventions in startling ways.

Despite his international renown and vaunted position as one of the 20th century’s leading modern artists, much about his work was intrinsically local. Miró was born in Barcelona in 1893, and maintained a strong connection to the city throughout his life. His art was deeply rooted in the rhythms, colours, sights and sounds of his native city, and his Catalan heritage deeply influenced his art. Considering Barcelona to be his greatest muse, as with his near contemporary Pablo Picasso Miró’s art often incorporated themes and symbols related to Catalan culture and history, as well as reflecting and responding to the political climate of the day.

Miró’s work is displayed in various Barcelona institutions and public spaces, but by far the best place to get to grips with his work is the Joan Miró Foundation, housed in a stunning bespoke museum on Montjuic hill. Intended as an accessible space where Barcelona’s citizenry could interact with contemporary art in a new way, the foundation was Miró’s own idea. He roped in his friend and renowned architect Josep Lluís Sert to help realise the project, and Sert’s fabulous concrete and glass building punctured with a series of courtyards and terraces is one of the world’s most impressive museum spaces.

-

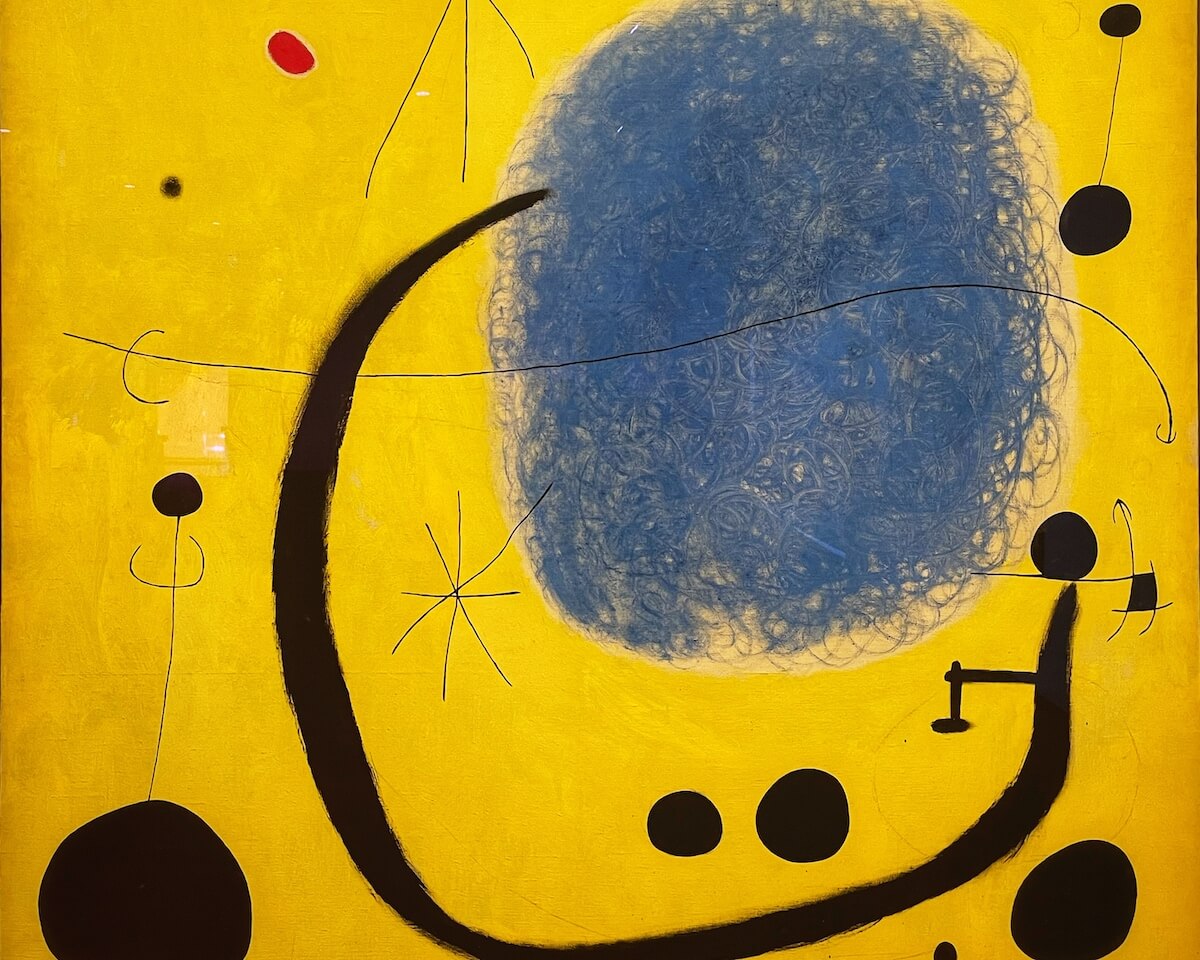

The Gold of the Azure

One of Miró’s most visually arresting works, this spectacular canvas from 1967 dazzles with its combination of bright yellow and blue paint overlaid with delicate celestial symbols lightly scratched onto the pictorial surface. As you drink in its magnificent chromatic harmonies and careful compositional balance, you might start to wonder about that wide curve of black pigment arcing towards the field of blue.

What is it? The flight of a bird? The passage of a star across the firmament? Or is there something vaguely human about the shape? As with all of Miró’s greatest works, the enigmatic quality of the composition resists a simple narrative explanation. In fact, it is precisely this resistance to fixed interpretation that renders The Gold of the Azure so poetic - and so hard to tear your gaze away from.

-

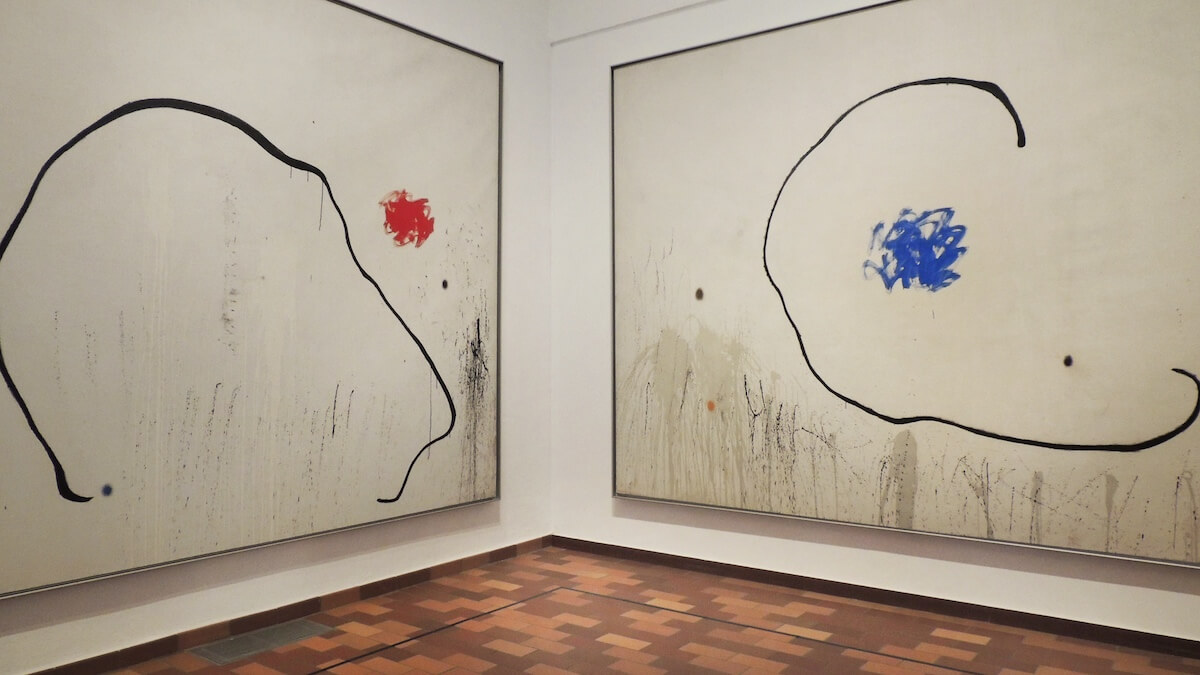

The Hope of a Condemned Man

Repelled by the illiberal climate of his home country and committed to progressive ideals of social change, Miró’s art practice was a highly political one throughout his career. In the aftermath of the second world war and the resulting Spanish Civil War, the Fascist dictator General Franco rose to power in his native country, shaping the political, social and cultural discourse of Spain and Catalonia for decades to come. Barcelona was a hotbed of democratic anti-Franco sentiment for much of the 20th century, and Miró was a prominent figure in this movement.

In this triptych from 1974, the artist refers to the execution of the Catalan anarchist Salvador Puig Antich, the last person to be put to death in Catalonia before Franco’s death the following year. The garotting of the young separatist in a Barcelona jail caused outcry, and provoked Miró to compose this lyrical exploration of life, death, and the infinite nature of the cosmos. The minimalist white canvas at the centre of the triptych is scratched and stained, as a slender black line circles a blue splodge of paint at the centre - representing infinity - without ever reaching it.

-

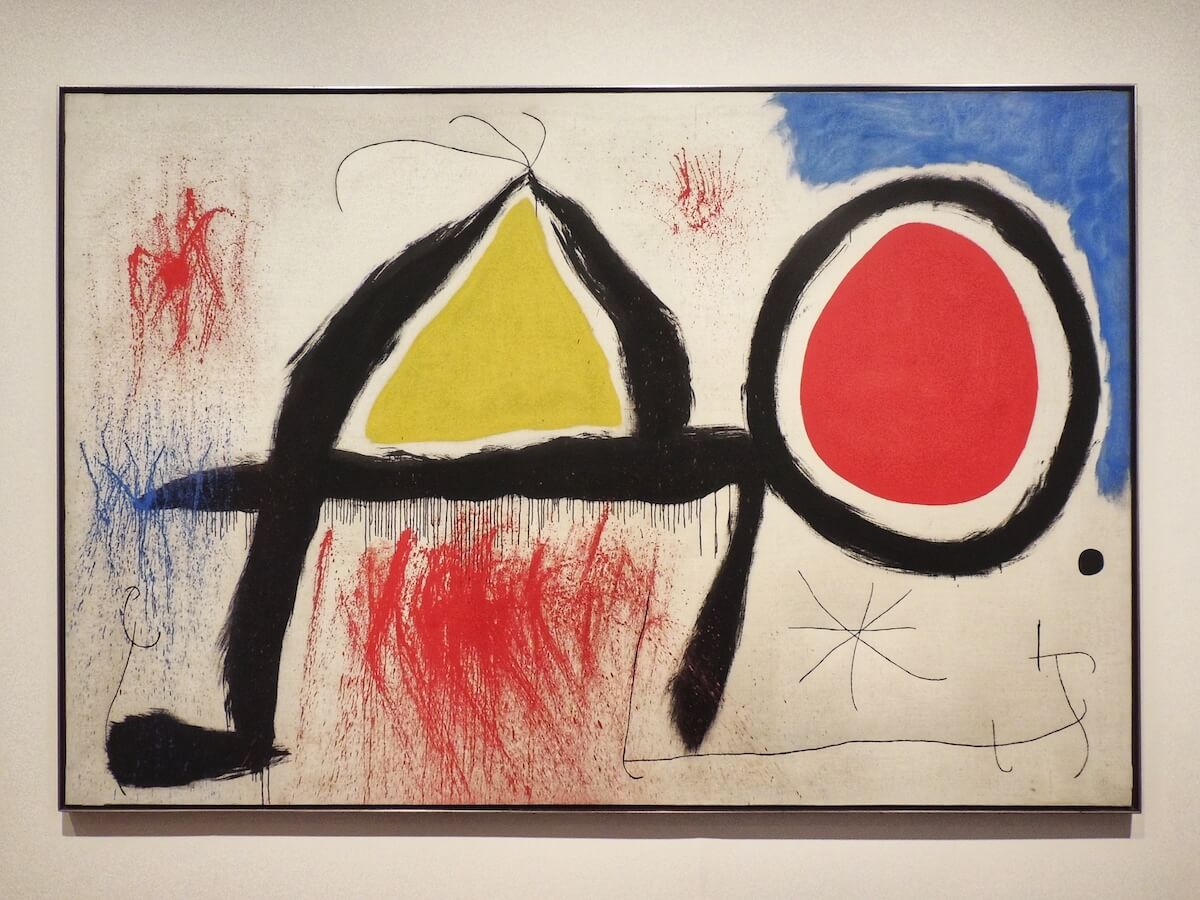

Figure in Front of the Sun

The massive Figure in Front of the Sun reflects a number of the influences that came to predominate in Miró’s artistic philosophy in the 1950s and 1960s. The sheer size of the canvas, in part made possible by his move to Mallorca - where his massive studio allowed him to work on a scale not possible earlier in his career - is a nod to the evolving work of American abstract expressionists like Mark Rothko, who had been inspired by him in their turn. So too are the streaks of pigment dripping freely down the surface of the painting - a Rothko trademark. The bright, primary colours meanwhile seem to reflect the sun-drenched landscape of the Mediterranean island that he called home in this period.

Perhaps most important for the genesis of Figure in Front of the Sun, however, was his visit to Japan in 1966. The mysteries of Buddhist philosophy and oriental symbolism had fascinated Miró for much of his career, and a newspaper cutting found amongst his papers describes a graphic work by the 18th-century Japanese monk Sengai that depicts a square, triangle and circle overlaid in a manner that recalls Miró’s painting.

In Sengai’s glyph the circle represents infinity, the triangle represents natural law, and the square is the origin of all things. The symbology of the Zen shapes profoundly appealed to Miró’s mystical sensibilities and constant search for abstract shapes that might reflect the mystery of the cosmos. In Miró’s re-imagining, the yellow triangle seems drawn inexorably towards the deep red circle which represents the sun, a recurring motif in the artist’s oeuvre.

-

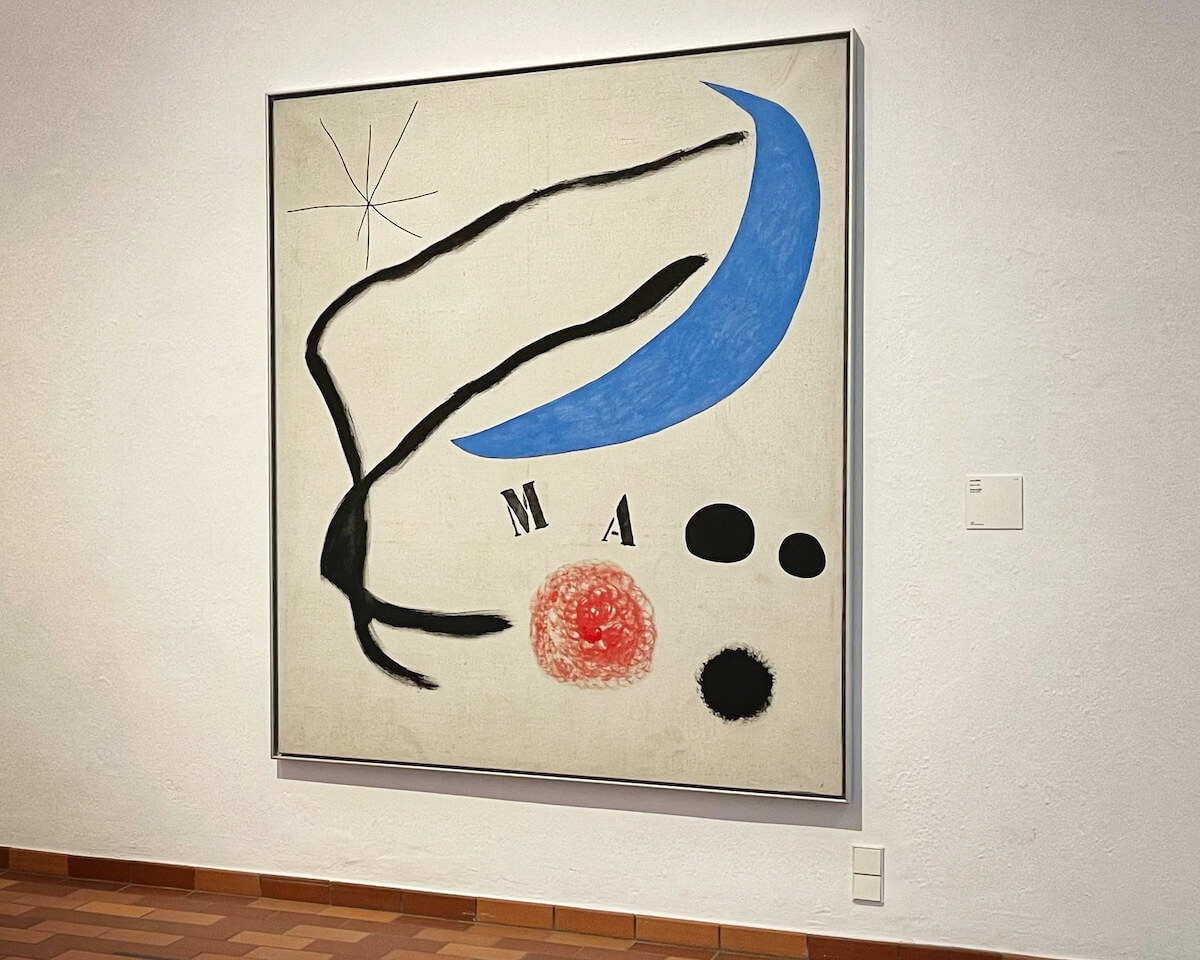

Poem (III)

Miró’s approach to the visual arts rejected the boundaries usually drawn between different artforms. Regularly mixing media in his works, snatches of typography appear regularly in the artist’s paintings. For Miró, these incursions of the written word were a nod towards the realm of poetry, a term that carried great weight for the artist. Poetry wasn’t merely a source of inspiration for his visual expressions, or a convenient analogy for his artistic practice. Rather, his works operated according to a poetic principle in themselves. As the artist wrote, ‘I try to apply colours like words that shape poems, like notes that shape music.’

The point is made forcefully in this 1963 work, titled simply Poem III. Miró was increasingly interested in the work of the concretism movement in avant-garde literature, where works of poetry adopted visual cues such as patterns and symbols interspersed among, or even replacing the text. Here the artist draws word and image together in a similar way, stamping the abstract canvas with typographic print.

-

Personage with Umbrella, 1931 (1973 replica)

As a committed avant-gardist and non-conformist, Miró strove to advance his art in unconventional ways throughout his career. Already in the 1920s he was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with painting as a medium of expression, wary of its claims to verisimilitude and unhappy with its limitations. In this overtly surrealist composition, a highly abstracted, priapic male figure stands tall, his enormous member almost provoking us with its challenging deconstruction of the human form.

Miró once wrote that “it is in sculpture where I will create a truly phantasmagoric world of living monsters” - the strange Personage with Umbrella appears to take a bold step in that direction.

-

Study for a monument (moon, sun and one star), 1968

Situated on the lovely North Patio of the Miró Foundation, this lyrical sculpture enjoys one of the finest views in all of Barcelona. From this perch high on Montjuic hill you can see all of the city spread out before you, sweeping away into the distance. Look carefully and you’ll see the soaring spires of Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia, before the Catalan capital gently melts into the crystal waters of the Mediterranean beyond.

Miró first had the idea for a massive, abstracted figure welcoming visitors to the city of Chicago in the 1960s. The 30-metre tall sculpture project was abandoned due to lack of funding, and the artist instead pitched the idea to Barcelona in 1968. The idea to install the work in the city’s Parc Cervantes never got off the ground either, but the Chicago authorities had second-thoughts in 1981, reviving the project and finally installing a 12-metre version of Miró’s work made from concrete, bronze, steel, wire and ceramic tile known as Miss Chicago.

The Miró Foundation’s scaled-down model features a vaguely female form with arms outspread in a gesture of welcome. A pared down mask with holes only for eyes takes the place of the figure’s face, whilst a four pronged crown juts into the skies above.

-

Pair of Lovers Playing with Almond Blossoms

Miró began to receive more prominent public sculpture commissions as his interest in the artform grew during the 1970s. One of the most prominent was a large-scale composition intended for the La Defense complex in Paris. The smaller version housed in the Foundation is a scale-model for the completed work, whose poetic title at first seems at odds with the gargantuan, primitive figures of the sculpture’s main protagonists. But on closer examination there is something strangely tender and delicate in the relationship between these brightly coloured, humanoid forms engaged in an enigmatic exchange. Who are the lovers, and what are they up to?

-

The caress of a bird

Miró’s playful sense of humour is fully in evidence in this slightly ridiculous sculpture located on the museum’s roof terrace. Inspired by surrealist and dada experiments in ready-made sculptures, Miró had been making artworks out of found objects from a very early stage in his career. He continued to do so even at the height of his fame, creating The Caress of a Bird in his Mallorca studio in 1967.

We are confronted by a 10-foot tall figure constructed out of found objects cast in bronze and painted in bright primary colours. The figure’s legs turn out to be an ironing board, whilst the distinctive shape of the torso is reliant on the original object - an outhouse toilet seat. The head is a straw hat turned on its side, and the little blue bird perched atop is in fact a stone with wings of clay. A turtle shell standing in for a vagina confirms the gender of the personage, while miniature footballs provide a humorous take on the figure’s buttocks.

Although a fundamentally light-hearted work, the sculpture’s iconised abstraction of the female form interestingly recalls ancient pagan fertility symbols, and also speaks to the artist’s desire to undermine some of the more conservative associations of the western visual tradition. Miró famously asserted that he wished to ‘assassinate painting’ with his art; here he at least strikes a blow against its conventions.

Sobreteixim with eight umbrellas, 1973

Despite being most famous for his vibrant paintings, we have already seen that Miró’s artistic investigations frequently moved beyond the world of pigment and canvas. In the 1970s, towards the end of his long career, Miró became interested in textiles, and produced a series of large-scale tapestries with his collaborator Josep Royo that attempted to bridge the gap between paintings and fabrics. As ever, Miró’s work in the medium was deeply rooted in his sense of place: the tapestries were inspired by the distinctively Catalan tradition of ‘sobreteixims,’ or very heavy, thickly spun pieces of woven wool.

The massive Catalan Sobreteixim with eight umbrellas from 1973 is one of the Miró museums most striking works. Taking up an entire wall of one of the Foundation’s galleries, compositionally the work strongly recalls Miró’s abstract paintings - but with a powerful new emphasis of texture and materiality. The rough weaving of the cloth is emphasised rather than downplayed, offering a highly textured support for the blobs and dashes of paint overlaid onto its surface. Adding to the multi-medial makeup of the work, eight umbrellas are affixed to the surface of the tapestry.

-

Tapestry of the Fundació, 1979

Emboldened by the success of Sobreteixim with eight umbrellas, Miró decided to craft an even more daring tapestry in 1979, desiging it specifically for the space in the Foundation where it still hangs today. Equally colossal as his earlier sobreteixim, the artist adopted a vertical format for the Tapestry of the Fundació, which consequently towers above visitors to the museum.

The highly colourful work features many hallmarks of Miró’s trademark style, including bold fields of primary colours, celestial symbols and a vague, almost uncanny sense of anthropomorphism in the abstracted figure gazing upwards. Here again the materials play a starring role - roughly spun cotton and scraps of threaded wool seem to drip down the surface of the tapestry as if they were drops of paint, recalling his experiments in earlier paintings like Figure in Front of the Sun.

Coming to Barcelona? Through Eternity Tours offer a range of private tours in Barcelona that take you to the best sites in the Catalan capital, including Montjuic hill. If you'd like us to create a personalised itinerary including an in-depth visit to the Miró Foundation, we'd love to help!