Death, as they say, is the great leveller, and the story of art has a long and proud history of reminding its viewers of man’s inescapably mortal nature. From bizarre iconographies like the medieval Danse Macabre to terrifying portrayals of a rampaging Grim Reaper wreaking bloody havoc in scenes depicting The Triumph of Death, the message is clear: no matter what power or privilege you have accrued on earth, be ready to shuffle off this mortal coil in a state of grace.

Perhaps nowhere is this idea more clearly expressed than in the tradition of the Memento Mori (literally ‘remember that you will die’), visual reminders of the inevitability of death that usually took the form of skulls, skeletons or otherwise decomposing bodily remains. In the dramatic and highly mystical world of Baroque Rome, displaying ostentatious memento moro on one’s tomb was a highly popular choice for wealthy 17th-century patrons, and dozens of these macabre funeral monuments are hiding in plain sight all across the city.

This week on our blog we’re featuring 10 of out favourites, all of which you can visit for free in Roman churches - the perfect Rome walking tour for Halloween! So steel yourself, and get ready for a walk through the land of the dead.

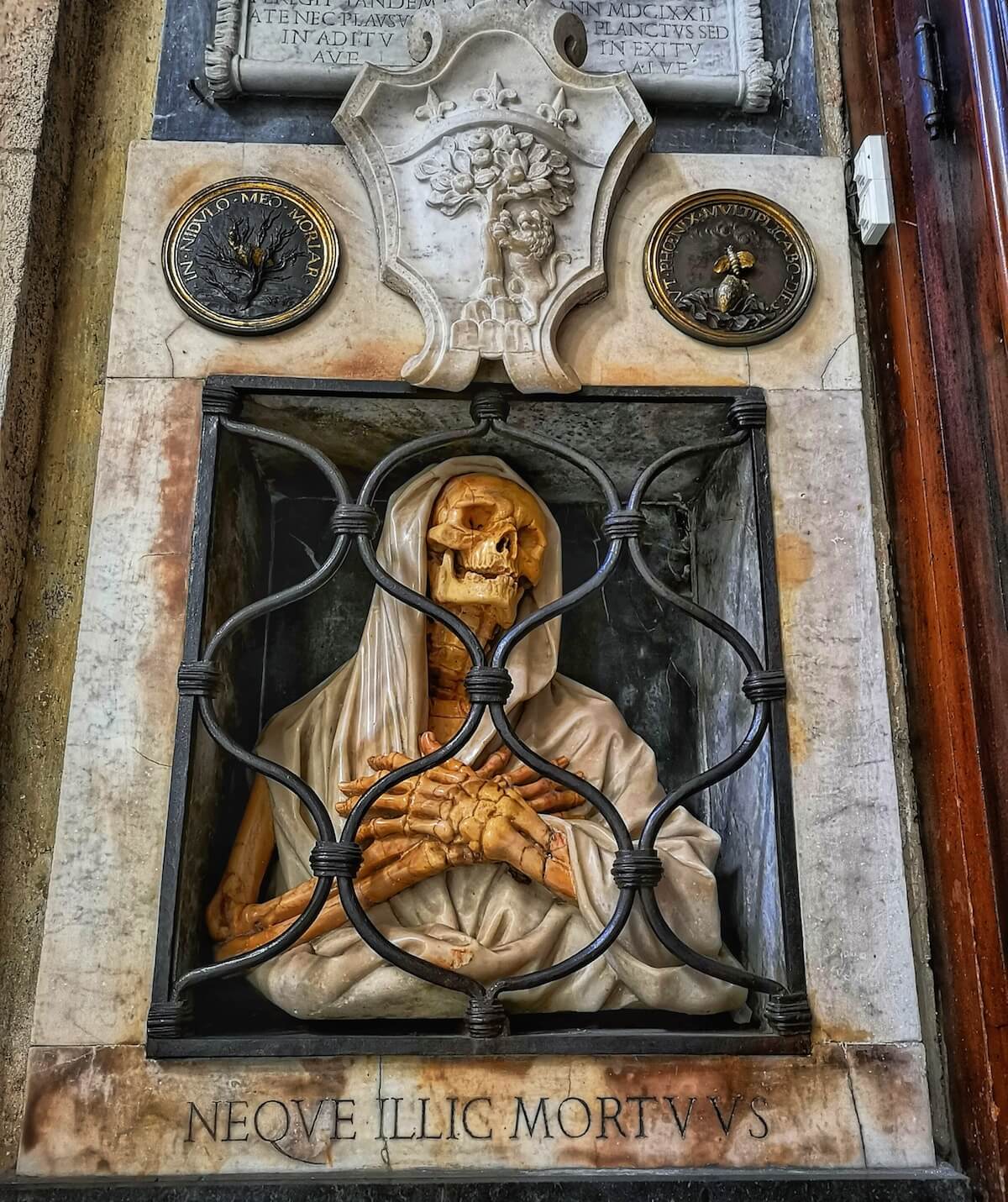

1. Monument to Giovanni Battista Gisleni, Santa Maria del Popolo, 1672

Dead men tell no tales...unless that is you're Baroque architect and musician Giovanni Battista Gisleni, in which case you're still cautioning generations to come about the inevitable march of mortality nearly 400 years after your own demise.

After a chequered career that saw him rise to a position of prominence in the Polish Royal court, Gisleni’s earthly remains found their final resting place in Rome's Santa Maria del Popolo, where the architect had the rare honour of designing his own sepulchre. Dominating the tomb is an incredibly creepy and animated skeleton, wrapped in a shroud and eyeballing (or rather eye-socketing) the viewer as he crosses his bony hands across his chest, imprisoned behind an iron grate.

Above, a painted portrait of Gisleni reveals a sober man of late middle age unconcerned by the horrifying skeletal apparition. An inscription explains the logic of the memorial: "Neque hic vivus / Neque illic mortuus" - not living here, nor dead there. Gisleni has a foot in both worlds.

The architect's tomb is just to the left of the church entrance and is without doubt one of Rome's most macabre sculptures - the perfect way to kick off our list.

2. Gianlorenzo Bernini, Monument to Urban VIII, Saint Peter’s Basilica, 1627-47

Fundamental to the concept of the memento mori is that death inevitably comes to us all, from the most penniless of paupers to the mightiest of popes. Even the all-powerful Urban VIII, great patron and builder of the Roman Baroque, was no match for the Reaper’s scythe, and the tomb of the Barberini Pope designed by Gianlorenzo Bernini in the apse of St. Peter’s Basilica crystallises the point. In contrast to some of the other entries on our list, however, the monument to Urban VIII is an altogether more triumphal affair.

At the centre of the ensemble the Pope himself sits enthroned high on a pedestal, hand raised in benediction. Flanking his sarcophagus beneath are personifications of Charity and Justice, exemplifying Urban’s virtuous character. Death himself reclines atop the sarcophagus, clad in a gilded hood and robes as he busily inscribes the Pope’s name into the Book of the Dead, immortalising him for all time. Even in death, Bernini’s greatest patron had no intention of being forgotten.

3. Gianlorenzo Bernini, Funeral Monument to Alexander VII, St. Peter’s Basilica, 1671-8

Popes come and go, but Bernini is always here. At least, that’s the impression that one must have had back in the 17th century, when the great Baroque master carried out commissions for no fewer than 8 separate pontiffs. The final masterpiece produced by Bernini, who was over 80 years old by the time the work was completed in 1678 (with ample help from his studio), was another Papal tomb. This is the fabulously polychrome and iconographically complex tomb of Pope Alexander VII, and it reads like a mission statement of Baroque sculpture.

The venerably bearded Chigi Pope kneels on a marble cushion at the top of the monument, lost in prayer. Just like in the earlier tomb of Urban VIII, representations of Charity and Justice look up in admiration at the deceased Pope, this time joined by Prudence and Truth. Charity holds a child in her arms, whilst Truth rests her foot on a map of the world, signalling the Church’s dominion over the earth. Death himself arrives below, his face shrouded by an immense polychrome marble shroud and clutching an hourglass.

4. Domenico Guidi, Monument to Camillo del Corno, Chiesa di Gesù e Maria, 1680

Taking the Bernini formula to a magnificently macabre extreme, Winged Death has metamorphosed into a swivel-eyed maniac in Domenico Guidi’s 1680 Monument to Camiillo del Corno. A rattling bag of shaking bones swathed in flowing robes, Death cackles uproariously at the sight of the hour-glass clutched in his skeletal left hand as he seems to dance a jig of his own devising - the danse macabre taken to a whole other level.

Above, a somewhat perturbed looking Camillo casts his eyes towards heaven, hands clasped in prayer. ‘Please God, save me from this lunatic,’ he seems to say. Flanking Death are two putti, who hold back tears as they extinguish the candles of Camillo’s life. Time is most definitely up.

Find Guidi’s masterfully dark take on the Baroque memento mori in the beautiful but often-overlooked church of Gesù e Maria on central Via del Corso. It’s just to the right of the entrance.

5. Ercole Ferrata, Monument to Giulio del Corno, Chiesa di Gesù e Maria, 1680

On the other side of the entrance to the church of Gesù e Maria, a very different meditation on the transience of human life meets our gaze. This time the work of Bernini assistant and collaborator Ercole Ferrata, the monument commemorates Camillo’s uncle Giulio and formed part of the same commission as Guidi’s work.

Here, though, Guidi’s terrifying Death is nowhere apparent; instead, Ferrata adopts a much more allegorical tone. Time himself emerges from above Giulio’s sepulchre on wings of marble, caught in the act of ripping a black cloth featuring the dead man’s epigraph in two. Notwithstanding this apparent affront to his legacy, the elegant Giulio del Corno, who features in a medallion above, understandably appears much less concerned by the goings on than his nephew across the aisle.

6. Unknown, Monument to Mariano Pietro Vecchiarelli, San Pietro in Vincoli, 1639

Impressive anatomical precision is the calling card of the macabre tomb of Mariano Vecchiarelli in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli. Here two identical skeletons stand tall carrying between them a marble portrait of the deceased, who modestly clasps his left hand to his chest in a gesture symbolising resignation to his fate. Beneath the portrait of Vecchiarelli, an inscription carved onto an illusionistic black drape pays tribute to the dead man’s ecclesiastical career.

Although the identity of the tomb’s sculptor is unknown, his ability to accurately convincingly render the skeletal protagonists demonstrates that he was an artist of no little ability.

7.Carlo Bizzacheri, Monument to Cinzio Aldobrandini, San Pietro in Vincoli, 1705

Don’t fear the reaper…Easier said than done when you’re standing before the tomb of the 16th-century cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini designed by Carlo Bizzacheri in 1705, located just a few metres from the macabre tomb of Vechiarelli in the nave of San Pietro in Vincoli.

Here Death really takes centre stage - a winged, grimacing skeleton holding an enormous scythe and hourglass, he looms menacingly over Aldobrandini’s rather modest polychrome sepulchre. Look out for shrouded Death’s brilliantly depicted spinal column, peeking out from behind his ribcage. Unusually, the cardinal himself is nowhere to be seen: instead, the family crest of the Aldobrandini lets us know who is buried within.

8. Domenico Guidi, Monument to Lorenzo Imperiale, Sant’Agostino, c1674

It turns out that Domenico Guidi, whom we earlier met in the church of Gesù e Maria, was something of an expert in carving macabre personifications of Death. A few years before creating the monument to Camillo del Corno, the sculptor was commissioned to provide a suitable final resting place for Cardinal Lorenzo Imperiali in the church of Sant’Agostino across town. The massive and complex monument was a roaring success, with a contemporary poem praising Guidi’s ability to ‘shape a living tomb from the dead relics of the heroic cardinal.’

Here the bare-breasted personification of Fame is pictured celebrating the many virtues of the deceased ecclesiastic, who kneels in prayer at the top of the composition. Fame is caught in the act of opening Imperiale’s coffin, out of which an eagle escapes and flies towards heaven - vivid guarantee that the cardinal’s renown will live on and carry over into the celestial realm. Death, meanwhile, once again a flamboyant bag of bones, looks on in impotent astonishment as the Cardinal’s memory escapes his devouring clutches.

9. Gianlorenzo Bernini, Monument to Alessandro Valtrini, San Lorenzo in Damaso, 1639

Perhaps the funerary monument that really kicked off the craze for increasingly macabre representations of a winged Death ushering patrons off the mortal coil, Bernini’s comparatively restrained monument to Alessandro Valtrini in San Lorenzo in Damaso features a rather cheery skeleton with ragged plumage carrying aloft a portrait medallion depicting the defunct Valtrini, framed by a black marble curtain.

Commissioned by Cardinal Francesco Barberini to commemorate the wealthy Valtrini’s support of the church, the monument was executed by Bernini’s assistants to the master’s design in 1639. Find the monument on the counter-facade of the church, just inside the door to the right as you enter.

10. Unknown follower of Bernini, Monument to Cardinal Stefano Durazzo, Santa Maria in Monterone, 1667

Hidden away in the side streets to the south of the Pantheon, the apse of the unassuming little church of Santa Maria in Monterrone is home to the impressively foreboding tomb of the 17th century archbishop of Genoa Stefano Durazzo. Durazzo’s monument is directly inspired by the now-established Bernini formula: a winged and skeletal death hovers menacingly above the prelate’s tenebrous tomb, carrying aloft a large medallion portrait of the deceased dressed in full ecclesiastical regalia. These days the tomb is empty, as Durazzo’s remains were repatriated to Genova shortly after its completion.

Hidden away in the side streets to the south of the Pantheon, the apse of the unassuming little church of Santa Maria in Monterrone is home to the impressively foreboding tomb of the 17th century archbishop of Genoa Stefano Durazzo. Durazzo’s monument is directly inspired by the now-established Bernini formula: a winged and skeletal death hovers menacingly above the prelate’s tenebrous tomb, carrying aloft a large medallion portrait of the deceased dressed in full ecclesiastical regalia. These days the tomb is empty, as Durazzo’s remains were repatriated to Genova shortly after its completion.