Right at the heart of the dense network of cobbled streets that makes up the beautiful and vibrant Trastevere quarter, magnificent Piazza di Santa Maria in Trastevere is one of Rome’s most enchanting corners. The steps of Carlo Fontana's majestic fountain in the centre of the piazza make for one of the city’s most enduring meeting-points, whilst the impressive bulk of the church that gives the square its name dominates the surroundings. On any visit to Rome, the venerable basilica and its charming piazza are absolute must-sees. To tie-in with the latest episode in our Travel Destination series, which sees Rob exploring the vibrant neighbourhood, this week our blog is taking a closer look at some of the artistic masterpieces that lie in store in the wonderful medieval church.

Origins: Santa Maria in Trastevere and a Bitter Papal Feud

Although the exact origins of Santa Maria in Trastevere are lost to time, a long-standing tradition claims that a place of Christian worship on the site was the first to openly host masses in Rome way back in the third century. The magnificent basilica we see today is a (relatively) more modern affair, dating to the 1100s, and owes its current form to the bitter conclusion of one of the great crises of the medieval church.

Although the exact origins of Santa Maria in Trastevere are lost to time, a long-standing tradition claims that a place of Christian worship on the site was the first to openly host masses in Rome way back in the third century. The magnificent basilica we see today is a (relatively) more modern affair, dating to the 1100s, and owes its current form to the bitter conclusion of one of the great crises of the medieval church.

In the year 1130, the papal conclave to elect a successor to the deceased Pope Honorius II had concluded with the election of two rival candidates, both from Trastevere: Gregorio Papareschi, who took the name Innocent II, and Pietro Pierleoni, henceforth nominated Anacletus II. Anacletus had the support of the Roman barons and cardinals, and Innocent was forced to flee the city. He would spend the next 8 years gathering support for his claim to the papal throne across Europe, and when Anacletus died in 1138 the stage was set for the return of the now universally recognised Papareschi.

On his triumphant re-entry to the city, Innocent declared the dead Anacletus an antipope. Still sentimentally bound to his native Trastevere, the new pontiff set about glorifying the quarter whilst simultaneously stripping all memories of his vanquished rival. And so he wasted little time in tearing down Anacletus’ titular basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere and rebuilding it in his own image - a permanent symbol of his long-awaited vindication.

Plundering magnificent ancient columns from the Baths of Caracalla as well as constructing a grand new transept and apse, the real highlight of Innocent's patronage was the extraordinary mosaic of Christ and a fabulously attired Virgin Mary enthroned in glory surrounded by saints and the now aged Innocent himself that he commissioned for the apse conch of the new basilica.

Nearly 900 years later, Santa Maria in Trastevere's apse mosaic remains one of the absolute high-points of the medieval mosaicist's art. But it’s not the only masterpiece to grace the interior of the church; just over a century later the magnificent mosaic was equalled, or perhaps even eclipsed, by another dazzling series of mosaics just below, created by proto-Renaissance pioneer Pietro Cavallini in the closing years of the 13th century at the behest of local bigwig Bertoldo Stefaneschi.

The Commission: Pope Boniface, Bertoldo Stefaneschi and Pietro Cavallini

In the late 1290s, Pope Boniface VIII announced that the first Holy Year or Jubilee in church history would take place in the year 1300. The principal pilgrimage destinations envisaged by Boniface were naturally enough the venerable basilicas of St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s. But the Papal planners wanted a destination too for Marian devotion to satisfy the more than 2 million pilgrims that would descend on Rome.

The most natural choice would have been the oldest church in Rome dedicated to the Virgin, Santa Maria Maggiore, but as the basilica was under the control of the Colonna family, sworn enemies of Boniface, this was a non-starter. Santa Maria in Trastevere soon revealed itself as an admirable compromise, conveniently located roughly halfway between St Peter’s and St Paul’s.

Bertoldo Stefaneschi, brother of Boniface’s friend and amanuensis Giacomo, was at the time busily planning his own funeral monument for the basilica, and was more than happy to join in the effort to enrich and improve the basilica in preparation for the upcoming festivities. Besides paying for a restoration of the 12th century apse-conch mosaic, Stefaneschi also called on the famous Roman artist Pietro Cavallini to come up with a series of mosaics narrating the life of the Virgin on the blank wall space beneath the earlier mosaic. In a dedicatory mosaic, you can see Stefeneschi himself humbly dedicating his commission to the Virgin and Christ as Saints Peter and Paul watch solemnly on.

The choice of Cavallini demonstrates that this was no ordinary commission. Although documentary sources relating to Cavallini are scant, the masterful artworks he left behind - proudly signed as pictor romanus - mark him as a pioneering exponent of a newly naturalistic art whose influence would be felt across Italy for centuries to come. Although the frescos Cavallini painted for the Roman church of San Paolo fuori le Mura were sadly destroyed in a devastating 19th-century fire, a surviving Last Judgement in Santa Cecilia in Trastevere as well as works in Assisi and Naples are vivid testaments of his era-defining talent.

But the six mosaics depicting scenes from the Life of the Virgin Mary in Santa Maria in Trastevere remain Cavallini’s most enduring creations, scenes whose daring investigations into the nature of 3-dimensional space, explicit references to the art of antiquity and pioneering expressionism combine to form one of the great masterpieces of medieval art. Read on for our quick guide to the mosaics, and make sure to bring a pair of binoculars when you visit the church so you can admire them in the detail they deserve!

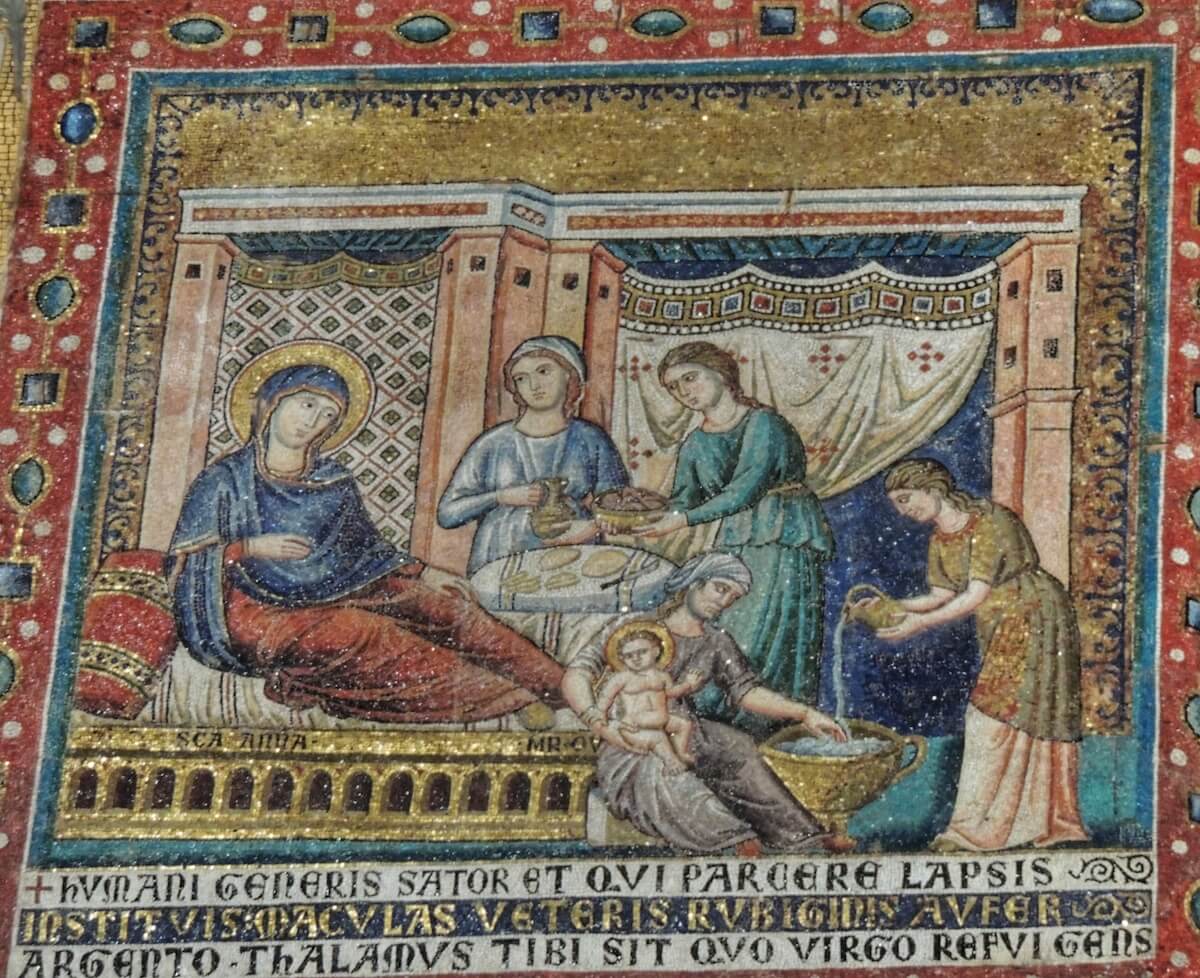

The Birth of the Virgin

This charming domestic scene takes place in an elegant bedchamber, where Mary’s mother St. Anne reclines at ease as servants provide drinks and sweetmeats to the new mother. Another servant pours water into a golden tub, whilst a fourth woman carries Mary on her knee, ready for her bath. In a highly unusual iconographic choice, the naked Mary stares frankly out at the observer. Fashionable wall hangings and precious materials suggest a palatial setting, the richness of the interior reflecting the elevated sacred status of the family.

The Annunciation

The archangel Gabriel strides purposefully into shot from the left, fabulously particoloured wings catching the breeze and elegant toga whipping behind him as he caught in mid-step. The now adult Mary, recognisable in her distinctive blue cloak, is seated in an elaborate architectural structure that gives Cavallini the chance to show off the strides he was making in perspective.

To either side of the Virgin a 3-flowered plant references the Holy Trinity whilst a tray of figs makes reference to Mary’s divine fertility. The Holy Spirit arrows towards Mary from God above, represented in the guise of a virile Christ. Hand on her heart and eyes cast sidelong towards the angel, Mary is clearly shocked at the message she has just heard. The poem below pays homage to the mother of Christ as a woman ‘blessed beyond all women.’

The Nativity

Perhaps the highlight of the mosaic cycle, the Nativity takes place in a rocky mountain landscape where Joseph and the pregnant Mary have taken refuge in a blasted cave. Beneath the light of an 8-pointed star, Mary has just given birth and reclines next to the manger where a heavily swaddled Christ is being observed by a curious ox and ass. Joseph, though he might appear to be asleep, is actually represented in the classical pose of a philosopher, contemplating the miracle before him.

To the right of the cave an angel hands a scroll down to a shepherd bearing the words ‘I bring you great joy.’ A boy plays music to a flock of sheep who drink from the waters of a river; a stream of oil flows from a nearby building into the river, identified as the ‘Taberna Meritoria’ - this refers to the founding legend of Santa Maria in Trastevere, which recounts that oil miraculously gushed forth from a tavern once located on the same site at the moment of Christ’s birth.

The Adoration of the Magi

Once again an 8-pointed star shines down from above, guiding kings from the east on a long journey to pay homage to the Holy Family. The story goes that the wise Magi were aware of distant prophecies made by the mystic Zoroaster that a child was to be born who would one-day become ‘king of the Jews.’ The sudden appearance of the blinding star convinced the group that the moment foretold in Zoroaster’s prophecy had arrived, and they set out following the propitious star. When the kings arrived in Bethlehem the star ceased its flight across the heavens, and the refuge of the Holy Family is soon found.

The three kings are represented in the guise of the three ages of man: young and fresh-faced Gaspar, who proffers myrrh to the grasping infant Christ; middle-aged Balthazar, who carries frankincense; and finally aged Melchior, grey hair and flowing beard caught in an invisible breeze, offering up a tray of gold to the newborn Messiah. Once again the poses of the figures, especially that of toga-wearing Joseph, are overtly classical, demonstrating Cavallini’s interest in reviving the aesthetic canons of antiquity.

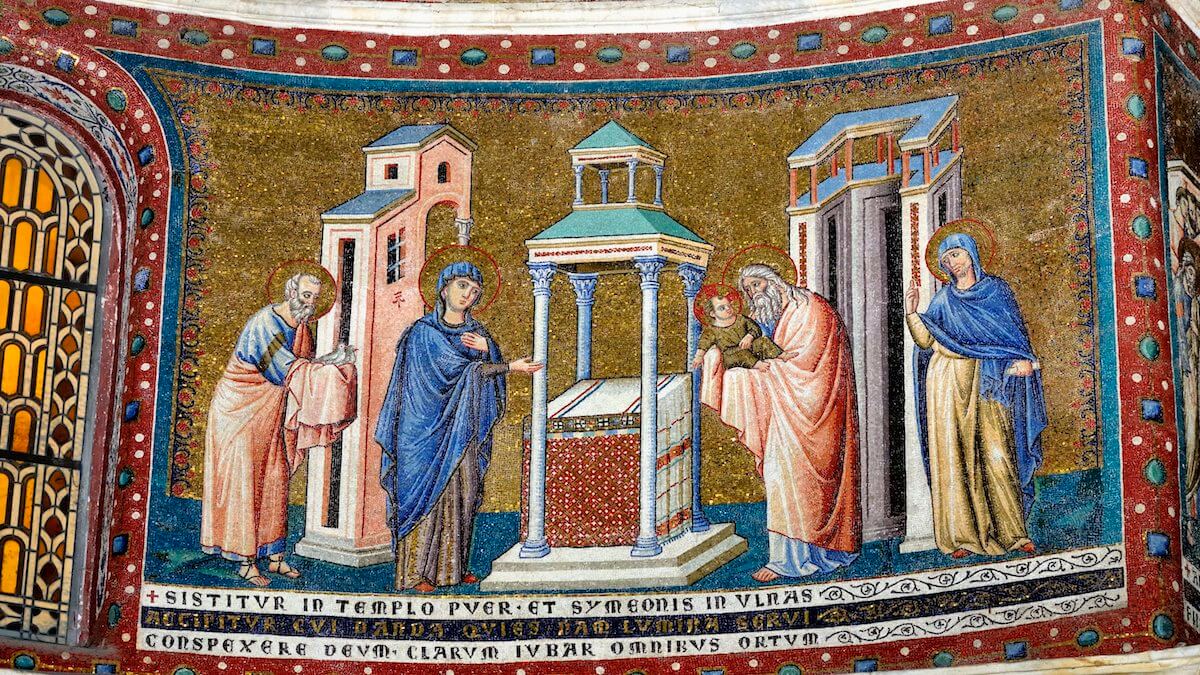

The Presentation at the Temple

This scene conflates two separate ritual moments in the early life of Christ: the Purification, which occurs 40 days after birth, marks the moment when the new mother is permitted to re-enter the Temple provided the family bring a sacrificial offering with them. The usual sacrifice would be a lamb, but poorer families were permitted to sacrifice two doves instead, and it is like this that the Presentation of Mary is traditionally depicted. Joseph, at the far left of the scene, carries the two birds in a cloth towards the temple.

The Presentation at the temple by contrast took place 30 days after birth, when Joseph brings the infant Christ to the temple to be welcomed into the Jewish community. The high priest Simeon holds the baby Jesus in his arms to the right of the altar, and the two exchange a wonderfully depicted tender gaze. This is the moment of Simeon’s epiphany, when he realises that he is holding the Messiah in his arms.

In this scene perhaps more than any other we can clearly see the precocious strides that Cavallini was making in the art of perspective: the architecture of the altar and the structure behind the prophetess Anna, who points heavenwards on the right of the mosaic, all recede in space, providing a convincing illusion of depth and three-dimensionality.

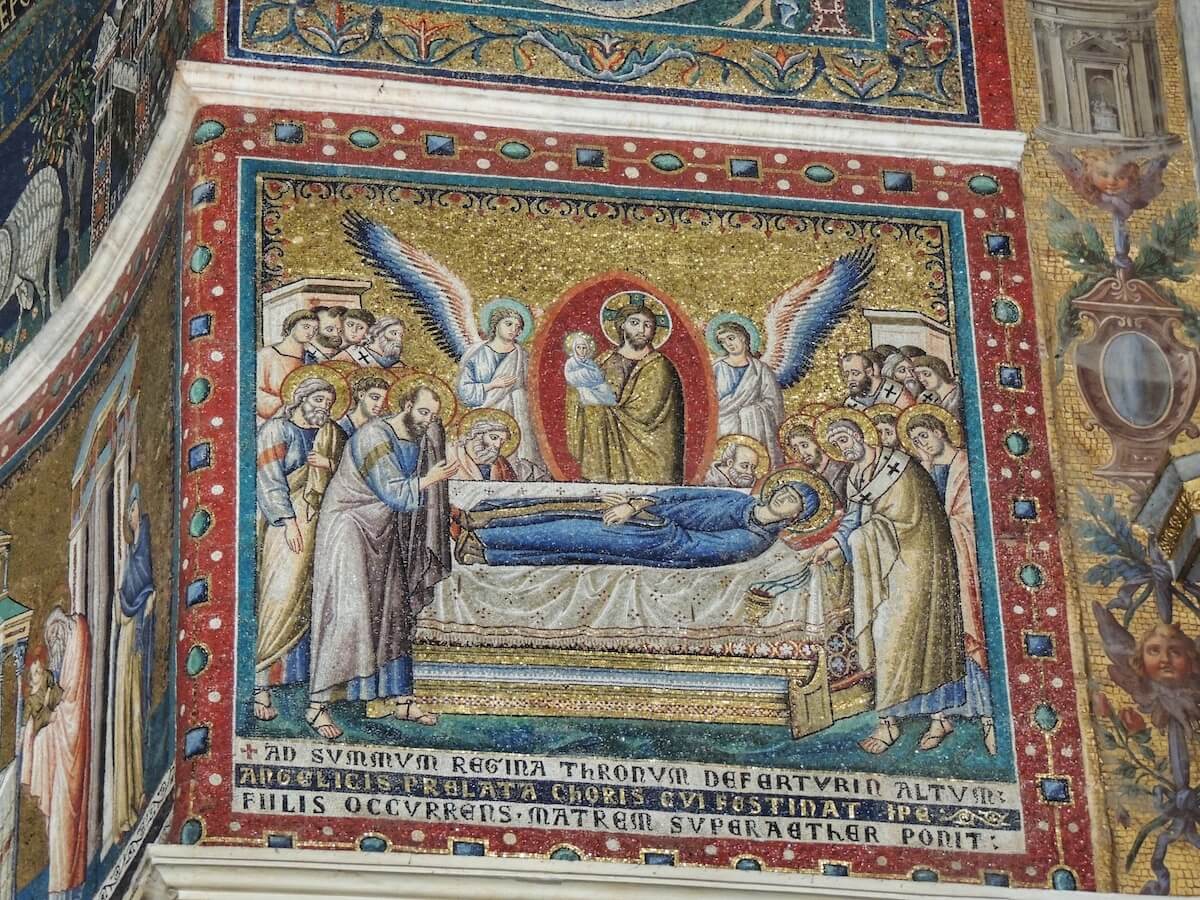

The Death of the Virgin

Cavallini’s extraordinary Life of the Virgin cycle ends where it must, with the death of Mary. At the centre of the composition Mary lies peacefully on a funereal bier, still draped in her distinctive blue robes. Arms crossed on her lap, she seems to be sleeping rather than dead. Around her Christ’s apostles mourn her passing. With beautifully rendered emotion, we can see St. Paul weeping at the foot of Mary’s bier. St. Peter swings a censer on Mary’s other side, performing the funeral rites.

Christ descends from a mandorla and gathers the infant-sized spirit of Mary into his arms to bring her back to heaven. In a wonderful piece of meta-pictorial logic, we realise that they are heading to the celestial sphere depicted in the 12th-century apse-conch mosaic above where the two reign over heaven.

That the two pictorial campaigns are meant to be seen as one is made clear in the poem beneath the mosaic:

Finally, the queen is conducted to the highest throne,

To her who, favoured above the choirs of angels,

The son hurries running to meet his Mother whom he sets high above heaven.