Few works of art invite such awe - or such head-scratching - as Michelangelo’s ceiling in the Sistine Chapel. Nobody who arrives at the spectacular climax of the Vatican Museums remains unmoved by what they see: Spanning over 500 square metres and teeming with over 300 figures, Michelangel’s frescoed ceiling is as much a theological epic as it is a visual masterpiece. Painted over four intense years, the frescoes present a sweeping vision of divine creation, human frailty, and the hope of salvation - but they don’t exactly hand over their meaning on first glance.

Behind the hypnotic beauty lies a tightly constructed narrative, one that draws from Genesis, classical antiquity, and the shifting spiritual currents of the Renaissance. But between the prophets, sibyls, nude youths and dramatic central scenes, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the sheer density of symbolism. If you’ve ever found yourself dazzled but confused by the mass of figures populating Michelangelo’s iconic vault, you’re not alone.

That’s why we’ve put together this guide to the iconography of the frescoes. Read on to find out exactly what’s happening up there — and why every detail matters.

What exactly is going on up on the Sistine Chapel ceiling?

q

q

The themes of Michelangelo’s work are extremely complex and require a little unpacking if you want to appreciate the full extent of his achievement as you gaze up at the distant ceiling from the ground far below. Originally, Pope Julius II was only expecting the artist to paint the 12 apostles on the ceiling surrounded by ornamental designs, but Michelangelo ultimately came up with something far more radical: the entire story of the creation of Man according to the Book of Genesis, subdivided into a large number of separate scenes by the complex architecture of the vaulted ceiling itself.

The scale of the undertaking is simply incredible: more than 300 separate figures people the ceiling’s 175 separate pictorial fields. Scholars disagree over whether a theologian had a hand in coming up with the complex theological programme, or whether Michelangelo devised the entire scheme himself. This would have been unusual, but given Michelangelo’s deep knowledge of the Bible, his formidable intellect and his tendency to do things his own way, it’s far from impossible.

Christ’s Ancestors, Prophets and Sibyls

Christ doesn’t appear in the decorations of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, but his presence is foreshadowed everywhere – the outer zones of the vault even give us something like his family tree! The ancestors of Christ appear in the lunettes surrounding the top of the chapel, distant family-members in whose veins ran the blood of the Saviour. On the cornice that runs all around the ceiling’s vault are the massive figures of seven male Old Testament Prophets and five female Sibyls, ancient seers who according to Christian thought predicted that the son of God was preparing to descend into the world of men. Each clutches the book or scroll that recorded their prophecy.

Jonah appears with the whale that swallowed him whole (although here it looks more like a giant fish), vertiginously foreshortened and turning to the right in defiance of the natural curve of the ceiling; Jeremiah strokes his beard deep in profound thought, whilst Ezekiel seems to swing around in startled surprise. These figures are the biggest in the Chapel, and were lauded for their beauty by contemporary authors as soon as the Ceiling was unveiled. The female Sibyls more often divide modern opinion.

The beautiful Delphic Sibyl is a stunning classical figure, but as with the rest of her companions, some might argue that Michelangelo has simply grafted a male physiognomy onto the female figures, who all have the extremely over-developed muscles of Olympic athletes. The ancient Cumaean Sibyl’s massive arms toned arms are certainly at odds with her tiny age-lined face! But their muscular physiques were certainly not accidental or the result of incompetence, and vividly express Michelangelo’s obsession with the monumental human form - for him this was the powerful symbol of mankind’s potential perfection as created in the image of God himself.

Noah Gets the World's First Hangover

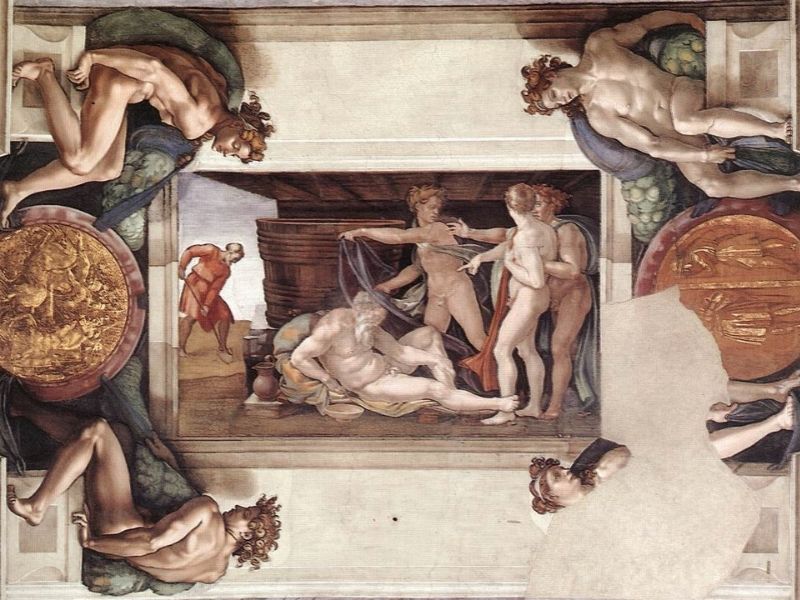

20 statuesque and athletic male nude figures known as ignudi recline on fictive architectural elements that divide the main space of the ceiling into nine separate framed images, and it is here that the major narrative scenes of Michelangelo’s fresco-cycle play out: the entire span of the Old Testament’s Book of Genesis unfolds in massive and highly colourful images peopled with magnificent figures whose gestures and expressions run the entire gamut of human emotion.

For practical reasons Michelangelo went about his task in reverse chronological order, painting the final moments of the Book of Genesis first: the earliest image Michelangelo painted was the Drunkenness of Noah: Noah has discovered winemaking but unfortunately is ignorant of its powerful effects, and passes out naked to sleep off the hooch.

The sozzled patriarch is discovered in his reduced state by his sons, and he gets into a family feud with his son Ham, whose heirs Noah curses for all eternity. The scene’s almost humorous tone might seem out of place with the seriousness of the other images on the ceiling, but it conceals powerful symbolism: many in the 16th century saw in Ham’s jeering reaction to his father’s inebriation a foreshadowing of the mocking Christ endured on his way to crucifixion.

The Deluge

The next image Michelangelo painted technically occurs before the drunken episode: this is the Deluge, in which mankind is punished with a devastating flood for the state into which it has fallen and where Noah is chosen by God to build an ark, save two of every animal and restart the faltering project of humanity. This powerful scene is full of visceral expressions of human desperation.

Groups of distraught naked figures desperately seek refuge on higher ground from the devastating deluge, and one figure clings hopelessly to the dead trunk of a blasted tree as the storm whips at her garments. A boat capsizes in the swirling waters, sending its occupants to their deaths, whilst off in the distance, the hull of the Ark firmly resists the onrushing flood. Completing the Noah images is the Sacrifice of Noah, perhaps the least interesting fresco in the cycle. Noah sacrifices a ram in thanks to God for saving him from the all-destructive flood. This fresco was damaged during an explosion when Napoleon invaded Rome in 1797.

Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden

After these first three frescoes Michelangelo moved his scaffolding and gazed up at the effect he had created - and was not entirely satisfied. The scale of the images were too small to have their desired impact on viewers craning up their necks from so far below, and so he changed his style: for maximum effect his figures had to become larger, and his compositions simpler – he was about to create the Michelangelesque style of painting that would change the art-world forever.

This new and more monumental ideal is clearly reflected in the next set of images and dynamic compositions portraying the story of Adam and Eve. In The Fall and Expulsion from Garden of Eden, Michelangelo combined the two scenes that paved the way for mankind’s tribulations over the entire course of human history, moments that have fascinated writers and artists for centuries.

The scene needs little explanation: a female human-snake hybrid coils around the Tree of Life in the centre of the image, and hands down the forbidden fruit to the willing Eve lounging provocatively on the rocks below. Adam has a part to play too, reaching up greedily towards the tree-boughs. This is just before the fall and so they are naked, feeling no shame in the purity of the beautiful bodies God has created for them.

That would soon change, and the inevitable result of their transgression takes place on the right: the archangel Michael drives the grief-stricken couple from the paradise of Eden at the point of a sword - Adam can’t bear to look back, and Eve wrings her hands in abject despair.

The Creation of Adam: A Trace Contact Between Fingers

The next images take us further back in time to where it all began for the human race, when things were looking so promising. According to Genesis 2, God decided that it wasn’t fair to let the newly created Adam go it alone in the world, and so resolved to furnish him with a mate. He takes a somewhat eccentric approach to the situation, putting Adam into a deep coma, splitting open his thorax and pulling out a rib, out of which he fashions Eve. Here the venerably bearded God takes a more hands-off approach, keeping his distance as Eve emerges from the out-for-the-count Adam’s side at the response of a single wave of the creator’s imperious hand.

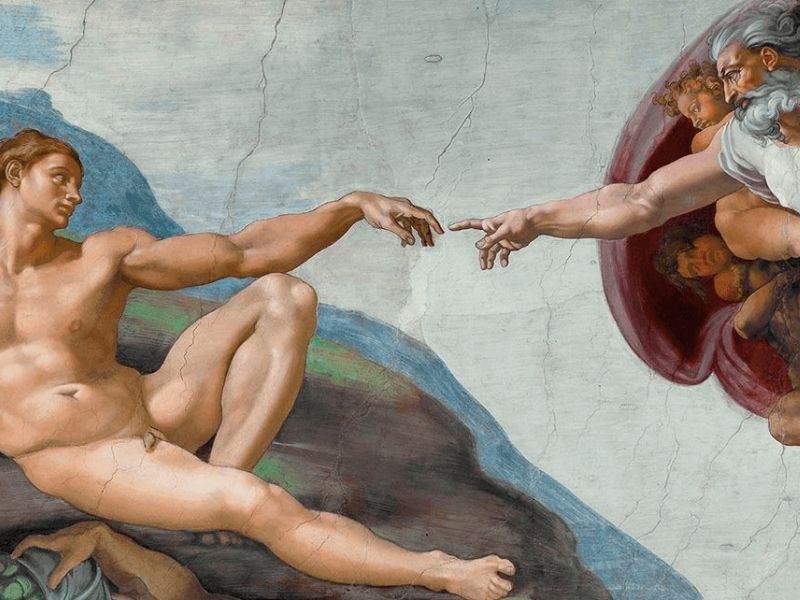

As we’re moving backwards in time, no prizes for guessing what comes next. At the very fulcrum of Michelangelo’s epic biblical narrative is the single most iconic gesture in the history of Western art: the trace contact between the fingers of God and Adam that breathes life into the world and begins the long story of humankind. Michelangelo has captured God right at the moment of creation itself, when Adam has already taken on his fully realised and perfect human form, but remains still a lifeless sculpture.

But then Michelangelo the divine painter does something Michelangelo the sculptor could never quite achieve – he sets blood pumping in Adams veins, transforms his inert body into living flesh, and turns that lifeless body into a living, breathing, thinking being. You’re probably so familiar with this image of two ideal bodies reaching towards each other with hands outstretched from its ubiquitous presence in popular culture that you might think it can’t surprise you. And yet gazing up at Adam’s sinuous and muscular form as light flickers into his eyes for the first time is a spellbinding experience.

The Creation of the World According to Genesis (and Michelangelo)

The final paintings in the series take us right back to the first moments of human cosmology, where God, more monumental and all-powerful even than in the previous images, conjures the world into existence as he swoops industriously through the air. In one scene, he Separates light from Darkness, bringing some structure to the primordial aether that existed before his act of creation. Rising powerfully into the sky in purple robes, God seems to rend the sky in two in a superhuman act of creation, appearing above us in extreme foreshortening and with chest and arm muscles rippling with exertion. Michelangelo’s famous contemporary biographer, Giorgio Vasari, considered this image to showcase the artist at the very height of his powers.

In the next image God performs a scarcely less impressive feat, Separating the world into land and water. This time the bearded God flies directly towards the viewer in another great example of foreshortening, forging the continents and oceans of the earth’s geography simply through raising his all-powerful right hand. Finally, in the third image of this sequence, God Creates the Sun, Moon, and the Planets by launching their forms high into the dark sky above, creating the cosmology of the world in the process.

This time, Michelangelo paints god twice – once from behind, where he is conjuring the world’s first plants from the ground, and once from the front, having just pitched the massive disc of the sun into the sky, with the moon’s orb ready for dispatch just behind him.

And so Michelangelo’s extraordinary depiction of mankind finishes just where the story of the world begins in a majestic piece of circular logic, past, present, and future colliding in the extraordinary labor of the master’s brush. The epic narrative of origins and being as outlined in the Genesis story had found its most iconic expression in the creative vision of the only artist with the skill, ambition, and sheer bloody-mindedness to pull it off - what more eloquent testament to Michelangelo’s achievement can there be than the fact that over 500 years later, when we think of these Biblical tales, we can’t help but think of them as Michelangelo has conditioned us to see them?

Through Eternity Tours offer a range of guided tours of St. Peter’s and the Vatican museums – join us and experience their splendor in company of our friendly expert guides.

CHECK OUT THE REST OF OUR SISTINE CHAPEL SERIES HERE: