In a city of grandiose landmarks and magnificent monuments, this is surely amongst the most surprising of them all. Proudly standing in front of the elegant Gothic church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva and with the soaring dome of the Pantheon as its spectacular backdrop, an elephant stands high on a pedestal, impervious to the boys organising impromptu games of calcio beneath his meaty marble feet. His head is caught in the act of swinging to the right, razor sharp tusks flanking a prodigiously long trunk snaking around the front of his body. Our charming pachyderm seems to be readying himself to sound a trumpet blast. But what on earth is he doing here?

To get to the bottom of the story, we must turn to the heavy load the elephant carries upon his back. Balancing precariously on a sort of ceremonial saddle is an obelisk carved from pink granite, all of five metres tall. Discovered miraculously intact in the gardens of the nearby Dominican convent of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in 1665, the artefact is a reminder that in antiquity the site was home to twin temples dedicated to the Egyptian deities of Isis and Serapis. Originally constructed on the orders of the Pharaoh Apries in the town of Sais during the 6th century BC, the obelisk was brought to Rome by Emperor Diocletian to decorate the temple.

The cults of Isis and Serapis were introduced to Rome in the 2nd century BC, during a period of enthusiastic Egyptomania, and they could count on many worshippers in the city. Egyptian obelisks would become a common sight in the ancient city at the height of the empire, carted across the Mediterranean after the subjugation of Egypt in 30 BC by a series of emperors, politicians and generals keen to make their mark on the urban landscape of the city (and that’s not to mention what is perhaps Rome’s greatest Egyptian tribute of all, the pyramid of Gaius Cestius).

Over a millennium later, the aesthetic power of the Egyptian obelisks was being rediscovered apace. Ever since the extensive campaign undertaken by Pope Sixtus V in the 1580s to rehabilitate and Christianise Rome’s ancient obelisks, the Egyptian monuments had become something of a calling card of the Baroque Eternal City - massive monoliths graced the piazzas in front of St. Peter’s, San Giovanni in Laterano and Santa Maria Maggiore, as well as Piazza del Popolo and many other grand public spaces.

The obelisk in Piazza del Popolo

The obelisk in Piazza del Popolo

Not long before, the Pamphili inspired redevelopment of Piazza Navona saw an obelisk rise towards the heavens at the centre of the square as the centrepiece of Bernini’s Fountain of the Four Rivers; the chance discovery in the Dominican convent gardens afforded the current pontiff - the Chigi pope Alexander VII - a perfect opportunity to follow in the footsteps of his ambitious papal predecessors.

Over the course of his 12 year reign the Chigi pontiff had dedicated vast sums and limitless energy to the improvement of the area of central Rome around the Pantheon, and so it was a natural step to order the erection of the obelisk in the piazza in front of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva. The eminent Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher set about interpreting the hieroglyphics carved into the four faces of the monolith in a syncretic, Christianised key. At the same time, the pope called upon Bernini (recently returned to Rome from the French court of Louis XIV) to come up with a plan for a monumental setting for the obelisk.

Various proposed designs ran the gamut from a simple architectonic ensemble featuring the heraldic mountains of the Chigi family guarded by torch-bearing dogs (a reference to a popular pun that described Dominicans as ‘domini canes,” or the hounds of God) - possibly authored by the Dominican Giuseppe Paglia instead of Bernini - to two audacious proposals in which the demigod Hercules uses his superhuman strength to drag the obelisk upright. But of all the options proffered, the Pope preferred a version featuring the highly unusual iconography of an elephant carrying the obelisk on his back.

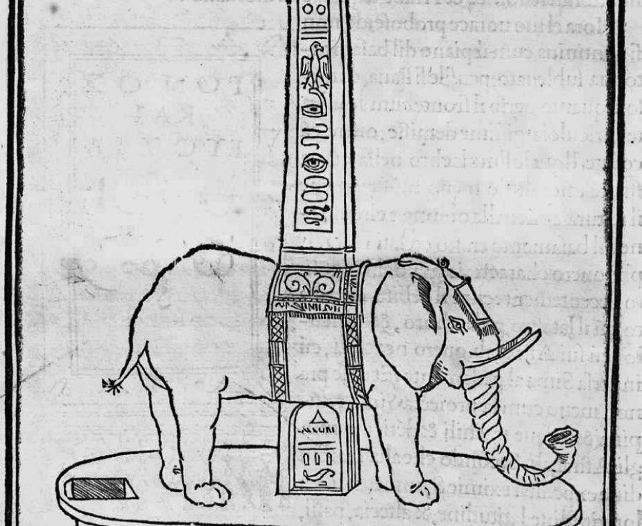

Woodcut from the Hypteronomachia Poliphili

Woodcut from the Hypteronomachia Poliphili

It seems that the Santa Maria sopra Minerva ensemble was directly inspired by the fabulously popular Hypteronomachia Poliphili, an erotic fever dream romance penned by the Dominican monk Francesco Colonna in 1499. Pope Alexander was a known admirer of Colonna’s work, possessing his own annotated copy of what was one of the earliest books printed in Italy. During one of the protagonist’s bizarre dream-like adventures he comes across a stone elephant carrying a monolith, and in the first edition of the text a woodcut representing the encounter bears a striking likeness to Bernini’s final design for the Santa Maria sopra Minerva monument.

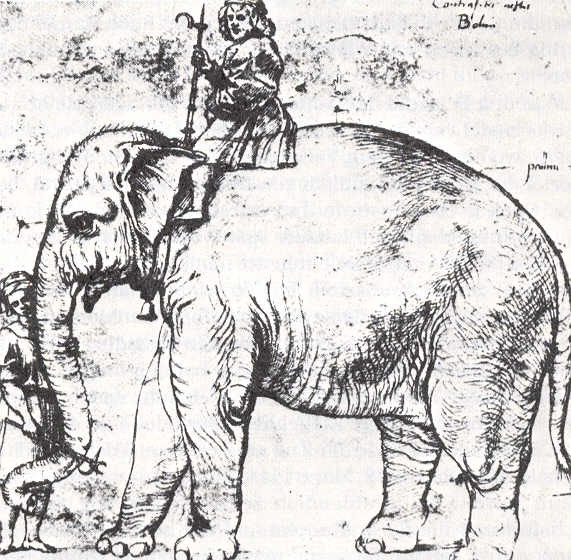

What’s more, pachyderms were very much in vogue in early-modern Rome. Exotic though they were, elephants were a semi-regular feature in the Eternal City during the 16th and 17th centuries. In 1514 the King of Portugal Manuel 1 gifted an elephant to Pope Leo X - the animal, christened Hanno, fast became the Pope's favourite pet, and was a regular feature in papal processions throughout the Medici pope's reign. Such was his fame that he was the subject of numerous poems and artworks, including a commemorative fresco by none other than Raphael, preliminary drawings of which survive.

Raphael, drawing of Hanno the Elephant

A little over a century later the the arrival of an elephant from the Orient in May 1630 caused a veritable sensation; the entire city rushed to catch a glimpse of the pachyderm, whose owner charged 1 giulio to see the animal displayed in a specially constructed barn. By all accounts he made a small fortune.

As with so many of Bernini’s public sculptures in Rome, numerous tall tales and urban legends surround the Elephant. Perhaps the most enduring is the apocryphal account of Bernini’s animosity towards Paglia, who was in charge of supervising the project and the building site, for forcing the artist to add a cube of marble beneath the elephant. In Bernini’s original drawing the obelisk was supported only by the pachyderm’s four legs, suspended over a spatial void in a gravity defying manner similar to many of his other Roman masterpieces.

The story goes that the traditionalist and unimaginative Paglia was horrified at the idea of such a great weight almost floating in mid-air, and demanded Bernini adjust his project to better support the obelisk.

In an attempt to mask the ungainly marble support beneath the elephant’s torso, Bernini added an elaborate ceremonial saddlecloth, but it’s fair to say that the somewhat stout pachyderm lacks the vertiginous, physics-bending magic of Bernini’s most famous public sculptures in Rome. Indeed, in deference to its chunky proportions locals soon conferred upon the stolid beast the nickname il Porcino della Minerva - Minerva’s little piggy. Over the centuries the vagaries of phonetics have transformed the nickname to the even more head-scratching Pulcino della Minerva - Minerva’s little chick.

To revenge himself on the Dominicans for daring to question his artistic capabilities and undermining the reception of the statue in the public eye, the story goes that Bernini decided to change the orientation of the elephant, which local lore claims is farting in the general direction of Paglia’s one-time office. The legend traces its origins all the way back to the 17th century, when the poet and humorist Quinto Settano penned an epigram describing how ‘the elephant turns his rear-end and trumpets with his trunk: Dominican friars, here I stand!’

The anecdote is a tall-tale - although Paglia may have prevailed in his desire to add an extra support beneath the elephant to ensure its durability, the supposedly bitter rivalry between Bernini and Paglia has little historical basis. In fact, the sturdy form of the elephant is fully in line with the goals of the commission as requested by the Pope, a visual metaphor demonstrating how wisdom requires a strong foundation as recorded in the inscription carved into the monument’s base: as the ‘strongest of animals,’ the elephant showcases how ‘a robust mind sustains deep learning.’

Nonetheless, the story of Bernini’s elephant obscenely saluting his Dominican rival is another wonderful example how artistic masterpieces and irreverent street life have co-existed side-by-side over the centuries in Rome like nowhere else on earth.

Bernini’s design was carved by his trusted and able assistant Ercole Ferrata, who had worked with the master on the angels flanking Ponte Sant’Angelo. After a little over a year of planning and execution, the monument was unveiled in the piazza in June 11, 1667. Unfortunately the Pope never got to see the final product, dying a month before its completion.

Bernini’s design was carved by his trusted and able assistant Ercole Ferrata, who had worked with the master on the angels flanking Ponte Sant’Angelo. After a little over a year of planning and execution, the monument was unveiled in the piazza in June 11, 1667. Unfortunately the Pope never got to see the final product, dying a month before its completion.

Next time you find yourself in the Eternal City, make sure to pay a visit to Santa Maria sopra Minerva to admire il Pulcino della Minerva, whose long swaying trunk curving into the aether is as daring in its defiance of the logic of stone as anything the great master ever created.