We all know what’s so special about the Sistine Chapel, right? The barnstorming tale of how Michelangelo’s extraordinary genius transformed the Pope’s private chapel in the Vatican into the greatest temple of Renaissance art that had ever been created, a work of individual creative virtuosity that has echoed through the story of art ever since. Elsewhere on our blog we’ve looked at the story of this magnificent space and created an in-depth online guide to Michelangelo’s frescoes so you know what’s going on way up on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, but this week we wanted to help you uncover the Chapel’s often-overlooked artistic treasures. Because Michelangelo was far from the only great artist to have picked up his brushes and left his mark here.

Indeed, even without Michelangelo’s iconic intervention in the opening years of the 16th century for Pope Julius II, the chapel would still be considered one of the great pilgrimage destinations for art-lovers from all around the world. Instead of discussing Michelangelo’s genius, however, visitors would be speaking in hushed tones about Botticelli, Perugino, Rosselli and Ghirlandaio. For these were the great masters of the Renaissance that Pope Sixtus IV turned to when he built the chapel between 1477 and 1482, fully 25 years before Michelangelo set foot in the Vatican palaces.

The Creation of the Sistine Chapel

The Sistine chapel takes its name from Pope Sixtus IV, who had the room constructed in place of the medieval Cappella Magna that once stood on the same site and was used for papal assemblies. The imposing new structure was fully 130 feet long and 42 metres wide, with a barrel-vaulted ceiling stretching more than 67 feet into the air. The stunning mosaic floor is in a geometric style of design known as Cosmatesque that harked back to medieval ideals of ornamentation.

Dividing the room in two is a beautifully decorated marble choir-screen, which separated the area reserved for the clergy around the altar from the spaces open to non-ecclesiastical audiences. Arched openings high up in the walls provide light, and members of the Papal court sat on stone benches lining three sides of the chapel during assemblies.

Of course it was only fitting that the finest painters of their generation would be called to Rome to decorate the Pope’s new chapel, and in the fifteenth-century the cream of the crop were almost all Tuscan or Umbrian (in those days Rome was ironically something of a cultural backwater, whose decayed splendour would only be slowly revitalised over the coming centuries).

Their beautiful frescoes stretch all along the walls of the chapel and depict the lives of Moses and Jesus Christ surmounted by portraits of the early popes above and fictive painted tapestries below. In Christian thought the Old and New Testaments were complementary texts, with events in the older work prefiguring what happens in the latter. In particular, the life of Moses was widely seen as reflecting and foreshadowing that of Jesus.

Linking the lives of Moses and Christ to the figures of the popes had an obvious propagandistic message, establishing them as the natural successors to the most important figures in the Old and New Testaments respectively, and placing Sixtus himself directly in this line of succession. This was Sixtus’ not so subtle way of re-affirming that it was he whom God had chosen to administer his affairs on earth. The narrative scenes from the lives of Moses and Jesus are stunning, and it’s really worth taking the time to give them a closer look when your neck needs a break from all that craning upwards towards Michelangelo’s ceiling. Read on for our selection of some of the highlights!

The Pope Holds the Keys: Perugino’s Delivery of the Keys to St. Peter

It is difficult to pick out highlights from the series, but perhaps the most important and beautiful scene of the lot is Pietro Perugino’s Delivery of the Keys to St Peter. In this scene, Jesus entrusts the founding of his church to Peter by giving him the keys of heaven, implicitly ordaining him as the church’s first Pope. This was the moment that signified the infallible role of all future popes as leader of the Christian world, and was obviously an appropriate message for Sixtus’ chapel. Elderly Peter kneels as Christ gives him the keys and the other apostles look on dressed in highly evocative Renaissance Italian clothing, while portraits of prominent contemporaries are mixed into the crowd.

Perugino was Raphael’s master, and in the older artist’s work you can clearly see from where Raphael got his taste for delicate figures, touching gestures and an innate sense of charm (for Raphael’s art in Rome, check out our comprehensive online guide). The large piazza shows Perugino’s mastery of perspective, and in the background we can see Jerusalem’s Temple of Solomon and Rome’s Arch of Constantine – Constantine was the first Christian ruler of Rome’s ancient empire, and provides another link in the chain of authority extending through the centuries and justifying Sixtus’ divinely ordained power.

The story goes that sitting beneath this image augured well for cardinals hoping to get elected to the papacy during conclaves – a number of Renaissance popes attributed their success to the power of Peter looking down on them.

Perugino was also responsible for the beautiful Baptism of Christ, where the on-looking crowd on the banks of the river Jordan are dressed in 16th-century finery and sport brilliant Renaissance hairstyles.

Botticelli’s Charming Christ and Fearsome Moses

Over the course of 11 months Sandro Botticelli too produced three wonderful frescoes for the chapel’s side-walls. The Temptation of Christ is classic a Botticellian composition, and the painting’s style will be familiar to anyone who has seen his works in Florence’s Uffizi gallery with their elongated forms, naturalistic details and highly expressive gestures. It was not for nothing that Peter Ustinov once remarked that if Botticelli were still alive today he’d be working for Vogue.

In this painting the devil tries to tempt Christ three times into betraying his upright values – on the left he suggests that the fasting Jesus turn stones into bread to sate his hunger; in the centre he attempts to goad Christ into throwing himself off a temple’s roof in order to test God’s promise that angels would always rush to his aid, whilst on the right Satan shows Christ a vision of the world’s incredible bounty which could be his if only he swears allegiance to the Dark Lord. Christ predictably enough resists, and forces the devil to finally reveal himself in his hideous true form.

As part of the Moses cycle on the other wall Botticelli also painted The Trials of Moses and the Punishment of Korah. Botticelli’s Moses cuts a seriously uncompromising figure. In the first scene, taken from the book of Exodus, the patriarch beats an Egyptian to death for hassling a young Hebrew boy, argues with shepherds trying to make life difficult for the daughters of Jethro, and finally leads the persecuted Jewish people through the desert to the Promised Land.

The subject of the next panel is The Punishment of Korah. This is Botticelli’s most important work in the chapel, and like Perugino’s scene also seeks to establish the infallible authority of the Pope. Here Moses cuts an even more fearsome presence than in Botticelli’s earlier painting: a group of disenchanted exiles rebel against Moses and Aaron during the Jewish flight from Egypt, and their punishment for defying the prophet is swift and horrific – the earth opens up and swallows the unruly rebels whole, never to be seen again.

On the left you can see fissures forming in the ground beneath their feet, their faces contorted into expressions of horror as they begin to sink downwards. The message being conveyed by the Pope’s choice of this scene to ornament his private chapel is about as subtle as a sledge-hammer, and must have been crystal clear to its visitors – if you dare to defy those chosen by God as his ministers on earth, retribution will be immediate and total. In other words, don’t cross the pope! As if it wasn’t clear enough already, Botticelli painted Aaron in the very centre of the composition wearing the distinctive headdress of the Renaissance papacy, a 3-tiered tiara called a triregnum.

Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Calling of the Apostles

‘And Jesus, walking by the Sea of Galilee, saw two brethren, Simon called Peter and Andrew his brother, casting a net into the sea; for they were fishers. And He said unto them, “Follow Me, and I will make you fishers of men.”’

One of the most prolific and successful of all Renaissance artists, whom you might know as having briefly been the master of the young Michelangelo, Ghirlandaio’s surviving contribution to the Sistine Chapel depicts the foundational moment in the Apostolic Mission when Jesus recruits the fishermen of Galilee as his first followers. The brothers Peter and Andrew kneel before Christ as they accept his charge in the surroundings of a stunning landscape complete with craggy mountains and crenellated fortresses overlooking the narrow sea.

But the real charm in Ghirlandaio’s painting lies in the motley crew of contemporaries he has included as modern witnesses to the Biblical event. To the right, a row of highly distinctive and individualised portraits thrust members of the most prominent Florentine families back in time to first-century Gallilee. At the centre is Giovanni Tornabuoni, the Pope’s treasurer and patron of Ghirlandaio in Florence, rubbing shoulders with members of the Soderini, Vespucci and Neroni families. Think of it as a who’s who of the Renaissance jet set, a particularly high-quality early-modern version of the society pages.

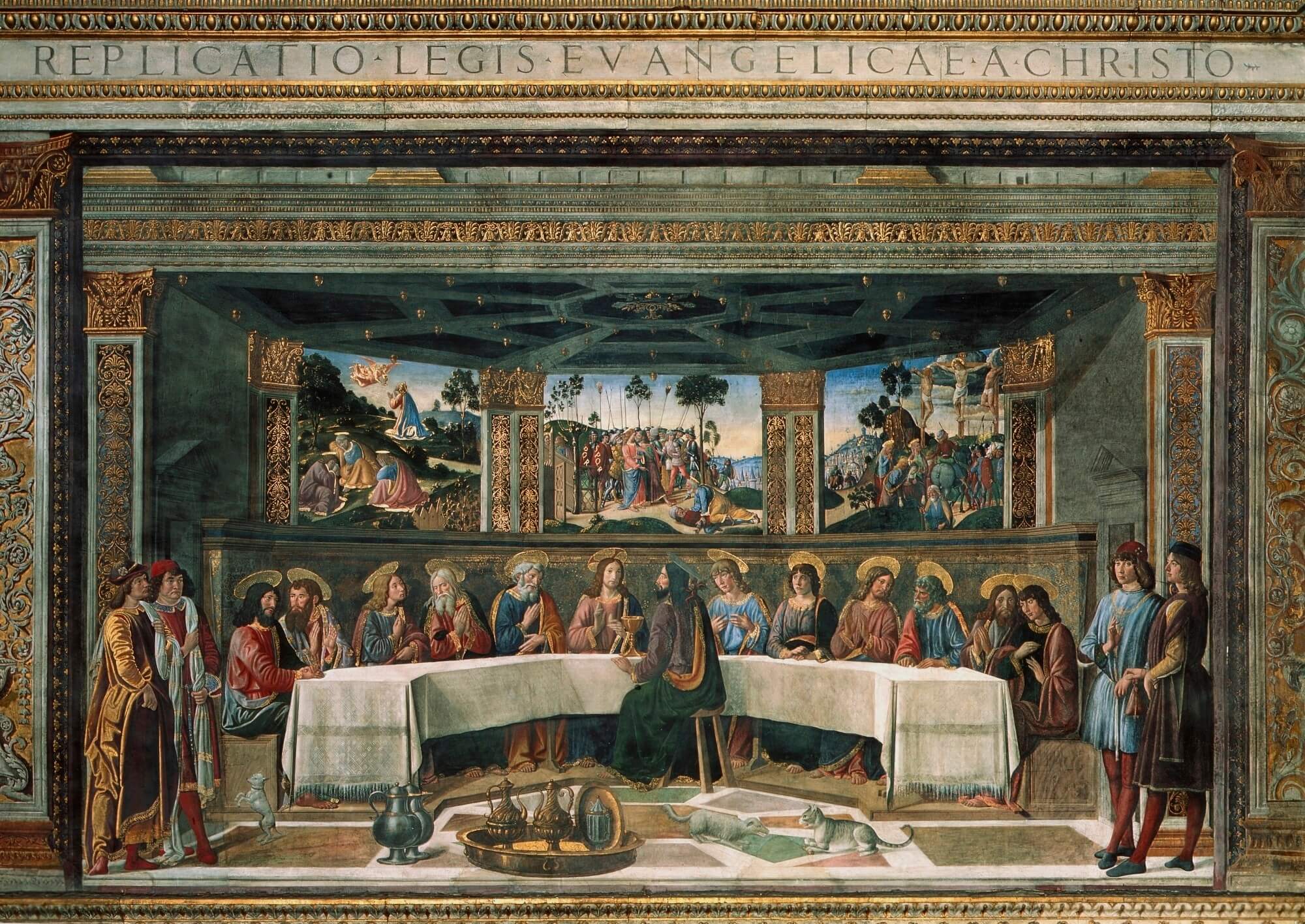

Cosimo Rosselli’s Last Supper

Okay so it might not quite match Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic rendering of the subject in Milan, but Cosimo Rosselli’s Last Supper in the Sistine Chapel is full of fascinating details and artistic innovation. Christ and his apostles are seated around a long horseshoe-shaped table, with the notable exception of Judas, whose back is turned to us as he faces the Messiah from the opposite side of the table. The soon-to-be traitor is already isolated from his peers, as a devil flitters about his ears. In the foreground a dog and a cat snarl at each other, prefiguring the discord amongst the disciples that is to follow.

In a fascinating piece of illusionism, three windows at the back of the banqueting hall lead onto other scenes depicting subsequent events, paintings within a painting. On the left the apostles sleep in the Garden of Gethsemane as angels appear to an insomniac Christ; in the centre, Judas plants a traitorous kiss on Chris’s cheek and St Peter slices off a soldier’s ear, whilst on the right the bloody final act of the Crucifixion unfolds.

According to the 16th century art historian Giorgio Vasari, Rosselli’s work was not particularly appreciated by his more famous colleagues in the Chapel, but Cosimo had the last laugh: Pope Sixtus himself was enchanted by his vibrant compositions, and shelled out more cash so that the artist could add more expensive pigments to his compositions. Roselli would also contribute the Descent of Moses from Mt. Sinai and the dramatic Crossing of the Red Sea to chapel’s fresco cycle.

The superb paintings commissioned by Sixtus IV for his new chapel offer a wonderful insight into the charming style of earlier Renaissance art. Their elongated and idealised forms are full of courtly grace, and provide a stark contrast to Michelangelo’s monumental and uncompromising vision of humanity nearby. In any other gallery in the world they would be absolute highlights of the collection, but here they are overshadowed by Michelangelo’s towering achievement.

When you reach the Sistine chapel do yourself a favour and don’t just look up; take the opportunity to gaze upon the frescoes along the walls, and admire these majestic under-rated masterpieces of Renaissance art.

If we’ve piqued your interest in these magnificent frescoes, then be sure to check out our special virtual tour of the Sistine Chapel for an immersive exploration of the history and art of the Sistine Chapel from the comfort of your own home!