The splendours of Rome’s Borghese Gallery are essential viewing for any art lover on a trip to Rome. Equal parts aristocratic pleasure palace and historic art gallery, the stunning villa is a treasure trove of Renaissance and Baroque art in the heart of the Eternal City. The fabulous edifice was the brainchild of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, the powerful Papal Nephew of Pope Paul V and one of 17th-century Rome's most irrepressible characters. Though ostensibly a man of the cloth, Borghese was much more interested in luxury than piety, and his unerring eye for artistic virtuosity allowed him to amass a private collection of art that had few rivals.

Masterpieces of painting and sculpture conjured by the hands of some of history’s greatest artists are arrayed in the Villa’s glittering halls and chambers - some commissioned, some gifted, and some stolen. Scipione's rapacious desire for artistic masterpieces was so great that he was known to have artists imprisoned to allow him to confiscate their works, and even went as far as stripping coveted religious paintings from their altars.

But Scipione was more than a common thug: he helped to launch the careers of some of the finest artists of the period, including the sculptor Gianlorenzo Bernini (read about Bernini's magnificent sculptures in the Villa Borghese here) and the painter Caravaggio, both of whom’s works feature extensively in the Borghese Gallery. No other gallery in the world can match the Borghese’s collection of six Caravaggio paintings - read on for our complete guide to Caravaggio in the Borghese Gallery!

Sick Bacchus, 1593

Caravaggio pitched up in Rome in the fall of 1592, a 20-year-old would-be artist with no reputation in his native Lombardy to speak of and few prospects awaiting him in the Eternal City. Genius, however, will always find a way. The Roman art scene was in something of a crisis in the final years of the 16th century, and wealthy patrons and connoisseurs were eagerly on the lookout for new artists capable of burnishing their collections. Caravaggio soon fell into the employ of the up-and-coming artist Giuseppe Cesari (also known by his honorific title the Cavaliere d’Arpino), in whose studio he excelled at naturalistic paintings and still lifes.

One of the most interesting paintings from this early period in Caravaggio’s career is the Sick Bacchus, where the incorrigible young Roman god of wine is looking exceptionally peaky after a trademark bender - sunken eyes, greyish lips and a jaundiced pallor betray the excesses of the sickly youth, semi-naked and wreathed in a garland of tangled vines as he clutches a bunch of grapes.

There is another hypothesis that might help explain Bacchus’ unhealthy appearance. According to contemporary reports, Caravaggio spent much of his first year in Rome seriously ill with malaria. The figure of Bacchus is an obvious self-portrait, and it appears that the artist decided to memorialise his illness (or give thanks for his recovery) within the narrative confines of the painting. In Caravaggio’s oeuvre, art and personal biography were deeply entangled from the very beginning.

Boy with a Basket of Fruit, 1594

Another work from Caravaggio’s time in the Cavalier d’Arpino’s studio, this truly sumptuous depiction of a youth holding a basket of fruit overflowing in its superabundance showcases Caravaggio’s rapidly developing skills in the art of still life. The scene seems to be drawn straight from the vibrant world of the Roman marketplace, where hale and hearty lads proffered just such wicker baskets of choicest fruit to buyers from the noble houses of the city’s aristocrats and cardinals. Some hypothesise that the youth was modelled by the artist’s friend Mario Minniti, or indeed that we’re looking at a self-portrait of a healthy-again Caravaggio.

Caravaggio seems to be rivalling the skills of mother nature herself in his depiction of these delectably ripe fruits: you can practically taste the sweetness of the grapes and peaches and apricots spilling from the boy’s arms. These realistic but idealised depictions of nature’s bounty delighted art connoisseurs like Caravaggio’s future patron Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, and helped launch him on the fast track to artistic superstardom in the Eternal City.

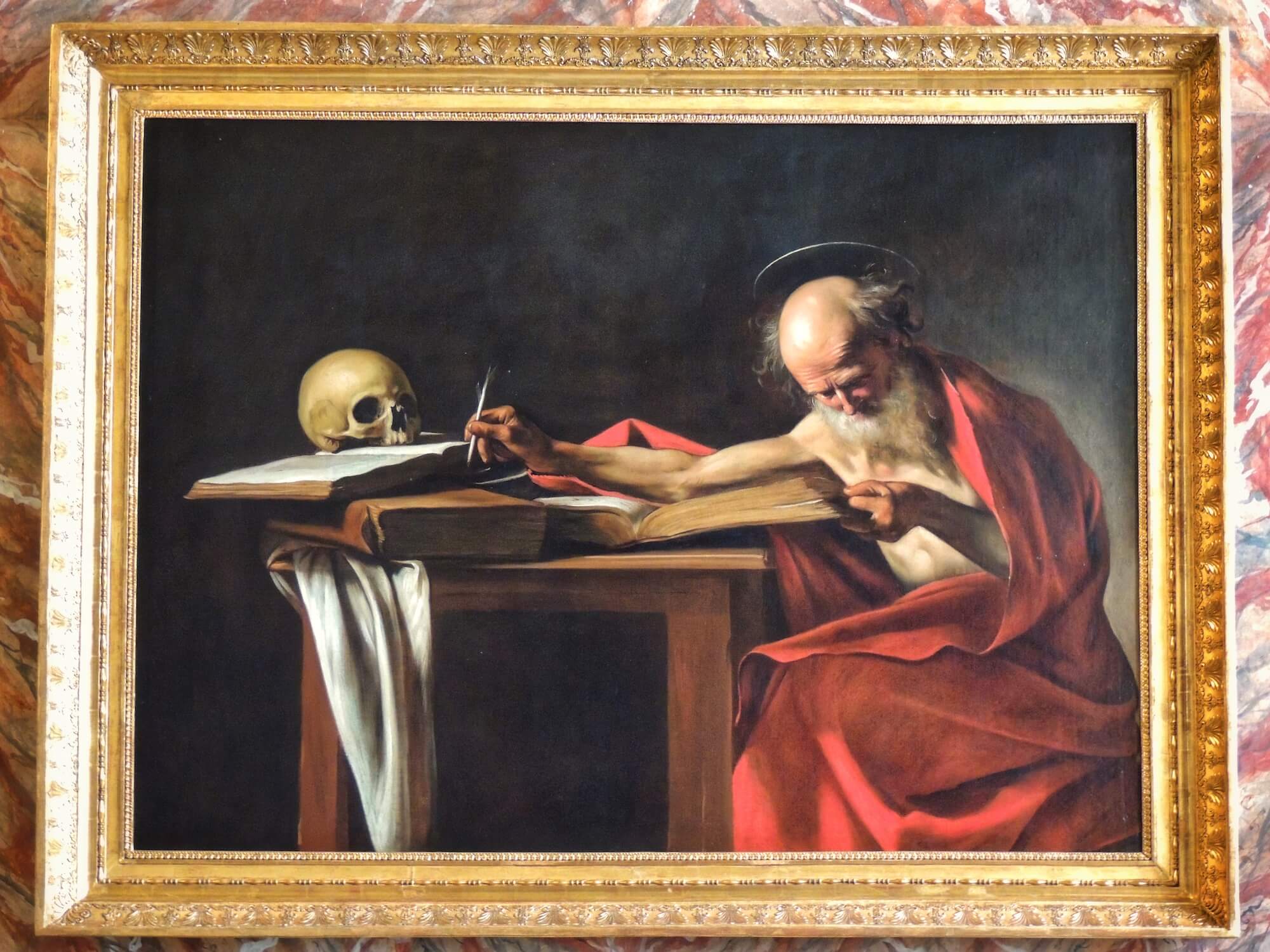

St. Jerome in his Study, 1605

Caravaggio relished the opportunity to paint figures on the margins of society throughout his chequered career, whether they be thieves or prostitutes, ascetic saints or martyrs. He would have ample opportunities to portray such a motley cast of characters in the somewhat gloomy climate of late 16th-century Rome; the brooding old Saint Jerome in the Borghese gallery, contemplating his own mortality as he goes about the arduous task of translating the bible in the company of a skull, is one of the best examples of this side of his art.

Once again, it is Caravaggio’s attention to detail and commitment to realism that makes the painting so striking, and that distinguished it so much from the work of his peers. Look out for the deep lines incised into the saint’s forehead, or the thick ruffled pages of the enormous ledger he grips in bony fingers.

The exact circumstances of the genesis of this painting are not known, but it might relate to a spot of bother Caravaggio got into with the law in 1605 (it wouldn’t be the first, or indeed the last time). Feeling insulted by some disparaging comments made by the rejected suitor of a young woman by the name of Lena who often modelled for him, Caravaggio brutally attacked the unfortunate Mariano da Pasqualone from behind under the cover of darkness one night in Piazza Navona.

The painter soon fled to Genoa, and only returned after apologising and agreeing to respect the peace in a signed affidavit witnessed by none other than Scipione Borghese. If, as seems plausible, Caravaggio painted the St. Jerome as a thank-you for the Cardinal’s intervention, it wouldn’t be the last time that he used his art to try to secure the powerful Borghese’s protection.

Madonna dei Palafrenieri, 1606

As part of the works ongoing at St. Peter’s basilica in the opening years of the 17th century, the Company of Grooms, or Palafrenieri, decided to commission a grand new altarpiece for their altar in the nearly-finished church. The subject was to feature the Virgin Mary alongside a young Christ and St. Anne, and Caravaggio won the commission thanks to powerful backers in the clerical hierarchy. The artist completed the painting with his usual speed, and delivered the canvas to the Groomsmen in March 1606.

The fabulous altarpiece features a startlingly beautiful young Mary supporting the faltering steps of her naked son, and together they stamp on a snake writhing at their feet. The message seems clear enough: Christ and the Virgin Mary, the latter so revered in the Catholic world and so derided in the Protestant north, combine to crush the stain of original sin emblematized by the serpent. Mary’s mother Anne, who supposedly miraculously conceived her daughter at an advanced age without any inappropriate help from her husband Joachim, watches on approvingly.

The altarpiece is beautifully painted, full of the pictorial and narrative details that make Caravaggio’s art such a delight: rich fabrics fall in luxurious folds; the curly-locked child hesitates before the snake in an entirely naturalistic gesture, and the contrast between young mother Mary and seen-it-all grandmother Anne offers a delightful meditation on the passage of human life.

Despite its evident mastery, however, the altarpiece was destined to only last for a month in its original location; church authorities declared it not fitting for the most important temple of Christendom, and porters carted it off to the humble church of Sant’Anna dei Palafrenieri on 16th April. Why the demotion? It seems that in the culturally conservative climate of Counter-Reformation Rome, the painting’s realism was considered unfitting for such a holy subject. Christ’s full-frontal nudity, although perfectly natural for his age, was unbecoming of the Son of the God. So too was Mary’s ample decolletage: though some argued this merely emphasised her motherhood, it also pointed to a sexualisation of the Virgin that constituted a shocking provocation.

Although Caravaggio’s barnstorming altarpiece proved too much for the delicate constitutions of the triggered churchmen, it proved a palpable hit amongst the more refined members of Rome’s cultural scene: poet’s waxed lyrically about the ‘angelic’ composition, and connoisseurs jostled to patronise the painter with commissions. The ever-wily Scipione went one better, quickly securing the painting from the Groomsmen for his private collection, where it still hangs today.

David with Head of Goliath, 1610

Soon after he completed the Palafrenieri commission, things went disastrously wrong for Caravaggio. The young Lombard was living life right on the edge, and despite his fame, trouble seemed to follow the painter wherever he went. Things reached a head on the 28th of May, 1606, when Caravaggio found himself involved in an armed brawl on a tennis court with local thug Ranuccio Tomassoni - some say the quarrel began over a bet, others over a woman, or even that tempers flared after a McEnroe-esque bust-up over a disputed line-call in a match between the two.

Whatever the cause, things soon turned nasty, and after much thrusting and feinting Caravaggio landed a (probably accidental) fatal blow on his rival. Badly injured himself, the painter went to ground and was soon forced to flee Rome with a price on his head. From then on, Caravaggio was a soldier to fortune; stints in Naples, Malta and Sicily led to more violence, feats of derring-do and a string of incredible masterpieces - a story we have recounted elsewhere. To cut a long story short, Caravaggio eventually tired of life on the run and pined for the Eternal City, hatching a plan for his return.

Knowing that he still had powerful backers in Rome keen to have the artist rehabilitated so that he could paint for them, Caravaggio decided to seek absolution for his crimes using the skills at his disposal: his brushes. He resolved to send the still-powerful Scipione Borghese a new artwork as a gift, representing the Old Testament hero David with the head of the slain giant Goliath. It’s a classic theme, but with a difference: in an act of daring bravura, Caravaggio unexpectedly painted himself into the narrative.

In a startling break from most traditional depictions of the victorious David (think only of Michelangelo and Donatello’s sculptures in Florence), gone is the triumphant hero happy to have vanquished a bitter rival. Instead, the young shepherd looks down with undeniable melancholy at the giant head he grips firmly by the hair, and as our own gaze is drawn towards the sullen, staring features of the defeated warrior we feel a jolt of recognition: it is Caravaggio himself who returns our gaze.

In portraying himself as the vanquished villain of the piece, the artist is seemingly owning up to his crimes and making the case that he has suffered enough. David’s compassion for his victim reflects the attitude Caravaggio hoped Borghese and the Papal court would adopt towards this ever-erring genius. His ploy worked, and in the summer of 1610 Caravaggio began the journey north from Naples to Rome, a letter of safe-conduct in hand and a pardon seemingly awaiting him at the Papal court.

St. John the Baptist in the Wilderness, 1610

David with the Head of Goliath wasn’t the only painting that the exiled Caravaggio painted in his efforts to curry favour with Cardinal Borghese. As he made his way back to Rome, convinced that his appeals had not fallen on deaf ears, the artist brought with him a cache of paintings that would tragically turn out to be the last images he would paint. Amongst the artworks that accompanied Caravaggio on his final journey was this melancholic imagining of John the Baptist, a figure that recurs in the artist’s oeuvre more than any other.

Caravaggio’s Saint John is a far cry from the dignified image of sanctity that we might expect. Taking the biblical account of John’s penitent wanderings in the desert to a literal extreme, here we are confronted with a downcast and unwashed adolescent seemingly plucked straight from the streets of the teeming southern city where Caravaggio painted him. The artist’s commitment to a darkly realistic idiom is absolute, and the only clues to the sad young boy’s identity are the traditional ram that accompanies him and the flimsy staff he leans on.

And what, you ask, of Caravaggio? After another terrible mixup, the artist’s journey to Rome was interrupted in a small town near Civitavecchia where he was imprisoned in a case of mistaken identity. The ship carrying his paintings continued without him and, after escaping jail, he set off after his property, convinced that they were the key to his salvation. This final quest at last proved too much for Caravaggio, who contracted a fever and died in the coastal town of Porto Ercole at the age of just 38.

All of Rome was distraught at the news, not least Scipione Borghese. Despite his despair, however, Scipione wasn’t about to give up on the promised paintings, and after much investigation and protracted wranglings got his hand on the promised St. John, which hangs to this day alongside the David in the Borghese Gallery - twin testaments to the magnificent art and tragic life of the Baroque world’s greatest painter.

We hope you enjoyed our guide to the masterpieces by Caravaggio in the Borghese Gallery! If you’d like to admire these stunning paintings in the company of an expert art historian, then check out Through Eternity’s private tour of the Borghese Gallery.