To celebrate the launch of Through Eternity’s Caravaggio in Naples virtual tour, this week we’re giving you a taster of the great Baroque master’s surviving works in the fascinating southern city. It’s a fascinating tale of violence and intrigue, epoch-defining artistic masterpieces and bar-room brawls all unfolding in one of the world’s wildest and most exciting cities. So read on to discover where to see Caravaggio in Naples!

Naples, October 1606.

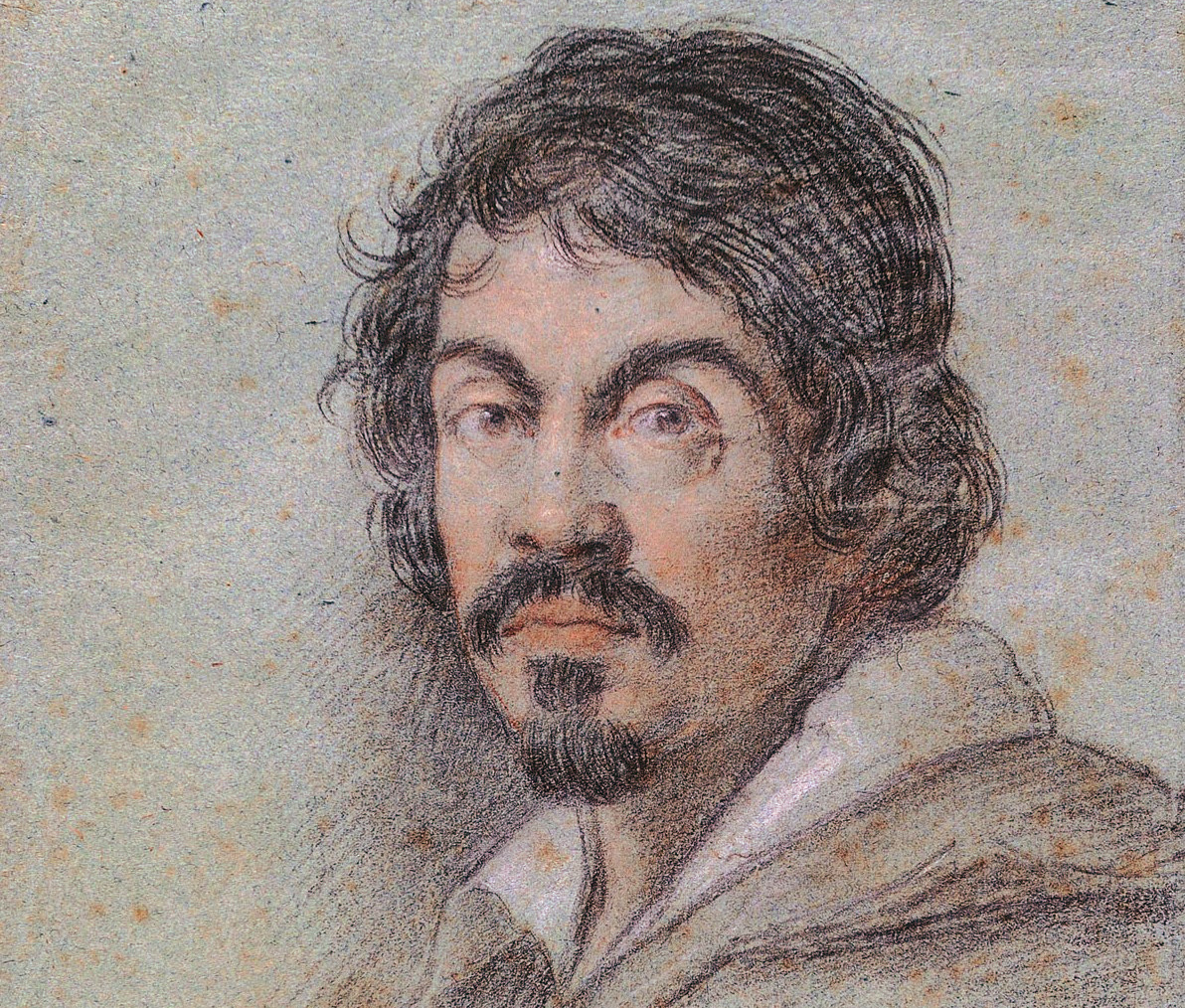

Michelangelo Merisi arrived at the gates of Naples as perhaps Italy’s most famous painter, the artistic reputation of the 35 year-old Lombard at his zenith. But the man that history would come to know as Caravaggio after the small town of his birth, usually so proud and haughty that every slight was answered with a cutting jibe or a slash of his sword, seems a shadow of his usual self - his face lined with worry beyond his years. For Caravaggio is a wanted man, and there is a price on his head.

How had it come to this? Well, the irredeemably violent artist had finally over-reached himself in the Eternal City, where he had spent a decade swaggering around town with a sword at his side. The artist’s latest escapade had gone horribly wrong, ending in his murder of his rival Ranuccio Tommasoni in a botched tennis-court duel. We have told that story elsewhere; suffice to say the that the Tommassoni clan had connections, the Farnese and Aldobrandini families amongst them, and Caravaggio’s powerful patrons were for once powerless to protect him from justice. A terrible sentence was swiftly passed down by the Pope: Caravaggio had been condemned to death under a banda capitale, meaning that anyone with the means and the motive was entitled to carry out the sentence.

Fortune’s wheel had taken a deathly spin against the man whose extraordinarily dramatic works had already changed the course of European art forever.

*******

But it wasn’t all doom and gloom. After a month zigzagging from one small town to another in the Lazio hinterland where he left rapidly-produced masterpieces in his wake for a string of provincial aristocratic patrons unconcerned by his desperate status, Caravaggio was ready for a return to the big-time. And Naples was an obvious choice.

At the start of the 16th century the Parthenopean city was far bigger than Rome, a cosmopolitan stew of fabulous wealth and shocking poverty barely kept in check by its garrisons of brutal Spanish soldiers in the pay of the viceroys of Europe’s most powerful empire. But despite its size and opulence, Naples lagged behind the Eternal City in its contact with the artistic avant-garde. It was a city, in short, crying out for the arrival of a painter such as Caravaggio.

What’s more, the Pope’s power in Naples was weak, and Caravaggio’s powerful protectors, the Colonna family, were highly influential - making Naples the perfect place for the artist to relaunch his career.

Caravaggio passed two sojourns in Naples, bookending the final years of his life; over these years he travelled widely in the southern Mediterranean, his footsteps continuously dogged by assassins and cutthroats. But despite his wandering lifestyle and increasingly erratic behaviour, the always productive Caravaggio if anything became even more prolific as his life hurtled towards its untimely denouement.

The dramatic real-life theatre of the Neapolitan streets and the city’s primal way of life clearly appealed to Caravaggio’s artistic sensibilities and his personal proclivities, and despite many of his Neapolitan works being lost or dispersed across the world over the past 4 centuries, today three absolute masterpieces of Baroque painting survive by his hand in the city. Read on to find out where you need to go to see them!

The Seven Works of Mercy, 1604, Pio Monte della Misericordia

Caravaggio’s reputation had clearly preceded him to Naples: barely a month after arriving in the teeming southern city, the artist already had his first commission - an altarpiece depicting the Madonna and Child surrounded by saints commissioned by a wealthy Sicilian grain merchant. The painting has disappeared without a trace, but before the altarpiece was finished Caravaggio was already at work on another, even more prestigious commission, and this one would become one one of the greatest canvasses in all of Baroque art: The Seven Works of Mercy.

This huge painting, also known as the Madonna della Misericordia, was intended for the high altar of a newly constructed church known as the Pio Monte della Misericordia. Founded by a group of seven young aristocrats, the so-called Monte della Misericordia was a charitable venture designed to provide aid to the pox-ridden destitute of Naples’ grim Hospital for the Incurables.

A central aspect of early-modern Catholic devotion was the performing of good or charitable works, and for the seven young founders of the Monte that meant mingling with the dirt and disease of the city’s most desperate denizens, humbling themselves in the service of Christ.

According to contemporary accounts, the noblemen went about their unenviable task with gusto, and their willingness to ‘serve those poor people, miserable and afflicted, buried in great torments, full of ulcers, and perilous and fatal illnesses without giving any sign of distaste’ garnered them much acclaim. In 1602 they decided to build a church just around the corner from the magnificent Cathedral to further their charitable project, and they wasted no time in calling in the services of the city’s latest celebrity to paint their altarpiece.

Appropriately given the mission of the institution, Caravaggio was asked to depict the famous acts of Christian charity descried by St Matthew via which man might be saved from a one-way ticket to hell: “For I was hungry and you gave me meat, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you took me in, I was naked and you clothed me, I was sick and you visited me, I was in prison and you came unto me." The acts of mercy described by Matthew had become a key part of Catholic piety, with the medieval addition of the burial of the dead making up the canonical seven works of mercy depicted by Caravaggio in such magnificent detail.

The subject matter might be biblical, but Caravaggio’s work is obviously taken straight from the anarchic world of the Neapolitan streets that surrounded the newly-arrived painter and invaded his senses: a dark and brooding tapestry of pilgrims and brigands, destitute beggars, foppish dandies and heavy-jowled innkeepers.

Just like on the Via dei Tribunali outside the church, here destitute poverty and luxury live cheek-by-jowl. A magnificently dressed young noble dressed in feathered hat and gloves imperiously cuts off a part of his velvet cloak and gives it to a grasping and naked beggar at his feet; a young woman offers her breast to a decrepit old man languishing in prison to nourish his ravaged body, flecks of milk staining his filthy beard - this detail is a repurposing of the ancient story of Cimon and Pero known as Roman Charity, transformed by Caravaggio into a shockingly naturalistic detail.

Nearby a pudgy hotelier obviously painted from life invites tired pilgrims into his inn; an exhausted worker slakes his thirst by drinking from the jawbone of an ass in imitation of the biblical hero Samson, whilst another figure struggles mightily with the dead weight of a corpse, a tangled of limbs being dragged laboriously towards burial. The dark night-time scene is dramatically illuminated by the guttering flame of a deacon’s candle, a virtuoso example of Caravaggio’s trademark chiaroscuro.

Everyone goes about their charitable tasks with a grim sense of duty: as ever, Caravaggio’s unflinching take on the world around him offers an indelible window into the the dark and dangerous world of the streets from where he drew his inspiration. Swirling in the air above are two impossibly beautiful angels swooping down towards earth on feathery wings, as the Virgin Mary approvingly watches over the terrestrial goings on clutching the infant Christ to her chest.

Where to see it: Pio Monte della Misericordia, Via dei Tribunali. €8. Mon-Sat, 9am-6pm, Sun 9am-2.30pm

The Flagellation, 1607, Museo di Capodimonte

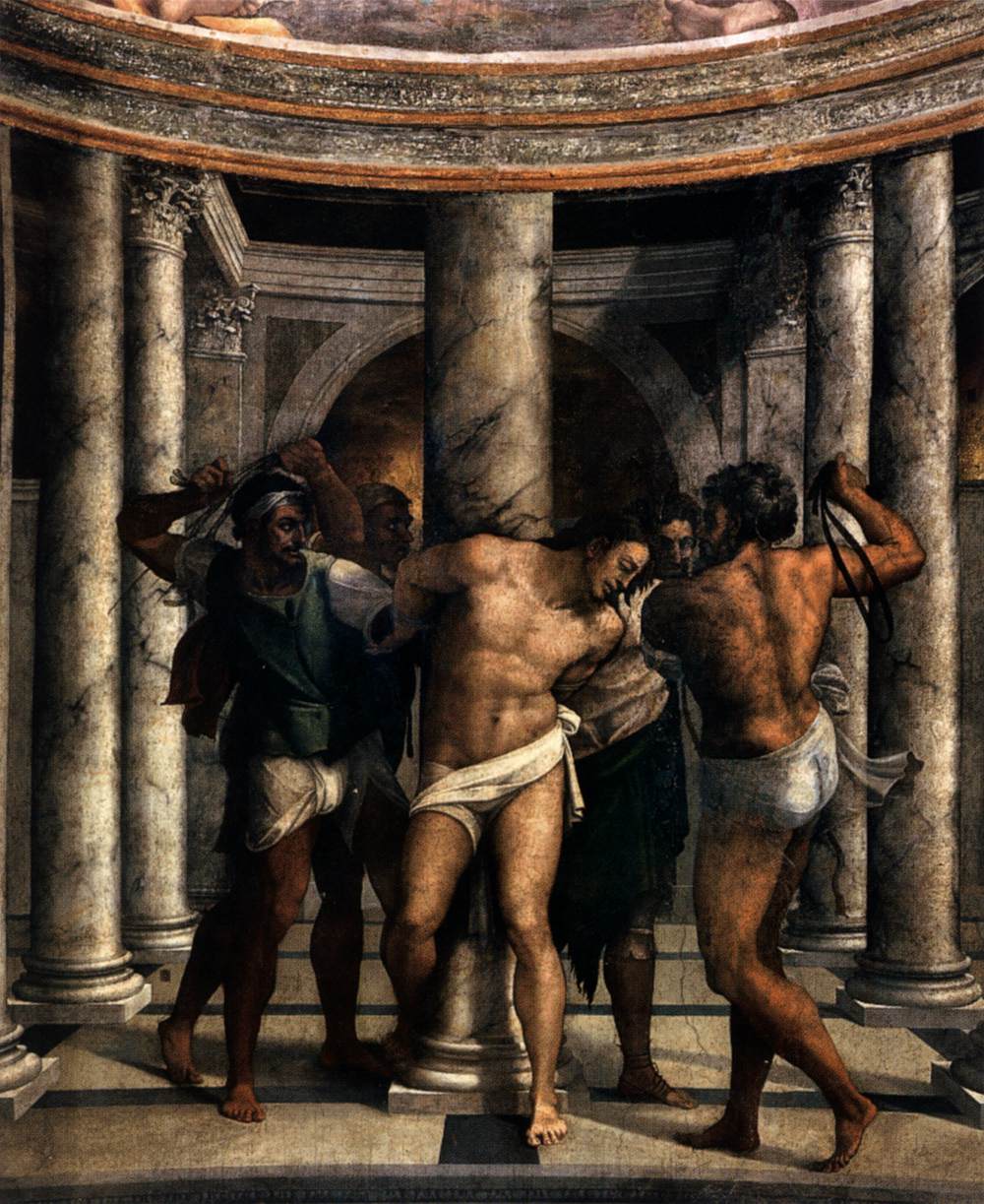

Caravaggio’s second major Neapolitan work is every bit as brooding as the Seven Works of Mercy, an austere take on one of the most unedifying spectacles in the entirety of the New Testament. Christ has seen his chances of being released from custody dashed by the base instincts of a baying mob, who convince Pontius Pilate to free the thuggish Barabbas instead of the innocent Son of God.

Christ’s long ordeal that will ultimately lead to martyrdom and death begins with him being tied to a pillar and whipped with unbridled ferocity. The version that Caravaggio provided for the de Franchis family’s chapel in the church of San Domenico Maggiore was a radical departure from conventional depictions of the subject. The classic and much-admired exemplar was Sebastiano del Piombo’s version in Rome’s San Pietro in Montorio, but the stately elegance of this Renaissance archetype was out of step with the dark austerity of Counter-Reformation religiosity. Caravaggio responded to the demands of the newly uncompromising spiritual mood with characteristic gusto.

The hunky Christ at the centre of Caravaggio’s composition is monumental and statuesque, his powerful torso spotlit in the otherwise gloomy canvas, but it is his tormentors who really catch the eye. One grabs a wad of Christ’s hair as he wrenches him against the column, whilst his grim-faced companion ties him in place with rough cords.

The naturalism of their ignoble actions is startling, bringing the biblical tale to life with extraordinary intensity. After the altarpiece was unveiled in 1607 local artists rushed to learn the principles of Caravaggio’s unique style - just as he had done in Rome, Caravaggio had conquered Naples in barely 6 months. But there was still the pesky detail of being a condemned man and a fugitive from justice to deal with.

Where to see it: Capodimonte Museum, €8. Thurs-Tues, 8.30am-7.30pm. Closed Wednesday.

Flight to Malta, Travels in Sicily, and Return to Naples

Caravaggio left Naples as abruptly as he had arrived, striking out for the rocky outcrop of Malta for reasons that remain obscure - although it seems likely that he made the journey in the hopes that it would help smooth his path towards an eventual pardon in Rome.

His year-long sojourn in the Knights of St John controlled stronghold of Valetta was certainly eventful: despite his lack of noble birth and status as a fugitive murderer (usually barriers for knightly preferment according to the rigid codes of chivalry), Caravaggio would quickly rise to the position of a knight of St. John, for whom he painted yet more masterpieces including an extraordinary Decapitation of St John the Baptist where his name is signed in the still-flowing blood of the executed saint. Predictably enough the good times were not to last, and Caravaggio was stripped of his knighthood for his role in yet another violent brawl with a fellow knight before staging a daring escape from prison across the sea to the Sicilian port of Syracuse.

A similar pattern would play out in Sicily, as the increasingly unhinged Caravaggio made and broke powerful connections, won sought-after commissions and made powerful enemies, wowed contemporaries with his feats of art even as his life hurtled from one tumult to another. Soon tiring of island life, by 1609 Caravaggio was back in Naples - where he was even more sought after than before. Convinced that unknown forces were out to get him (whether as a result of his sentence in Rome or his dispute with the Knights of Malta is unknown), Caravaggio slept with sword drawn - and his fears were well founded.

Shortly after his arrival he was set upon by four armed men in the Osteria del Cerriglio, a drinker’s paradise in the centre of the city that laid claim to being one of Europe’s most renowned watering holes (it’s still going strong today after over 700 years in operation). The painter survived the ambush by the skin of his teeth, but his face was so badly scarred that he was apparently almost unrecognisable.

Despite his injuries, Caravaggio if anything became even more prolific. Given the storm clouds swirling above his head it’s unsurprising that his works became even more brooding than ever before, stark and scaled-back meditations on death and human frailty.

From this period come the Crucifixion of Saint Andrew now in Cleveland as well as the incredible David with the Head of Goliath (a macabre self-portrait) in Rome’s Borghese Gallery as well as Salome with the Head of John the Baptist in the National Gallery in London. But the only work to remain in Naples from Caravaggio’s second spell in the city is the painting that may well have been the last to spring from the master’s brush: The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula.

The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula, 1610, Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano

Commissioned by the Genovese nobleman Marcantonio Doria to celebrate his stepdaughter’s decision to become a nun and take on the name Sister Ursula, Caravaggio’s rendering of the saint’s martyrdom is stark in the extreme. According to the legend, Ursula was a British princess who was murdered along with her absurdly large-retinue of 11,000 virgin companions after she rebuffed the advances of a Hun chief in Cologne.

Eschewing the more fanciful aspects on the story, Caravaggio pictures the moment the jilted Hun pierces the princess with an arrow, the young Ursula feeling her mortal wound with an air of faint disbelief. The killer’s face is a study in impotent fury, whilst his soldiers seem paralysed with shock at the wanton crime. But it is the figure whose face is spotlit against the inky background on the right of the scene that really catches our eye.

Just as he had in the Taking of Christ and the Martyrdom of Saint Matthew years earlier, Caravaggio has included himself as a witness to the violence. Mouth agape in surprise, Caravaggio strains for a better look at the crime with a mixture of revulsion and grim fascination: his obsession with the darkest impulses of humanity had never been clearer.

But despite the universal acclaim with which the painting was met (a contemporary report recounts how all who saw it were ‘astounded’), it was to be the last Caravaggio would ever paint. Shortly after the work was compete, the artist was on the move again, a safe-conduct in hand and a pardon finally awaiting him in Rome. The fates would never have it so easy for Caravaggio, though, and he never made it back to the Eternal City, dying of fever in mysterious circumstances in the Tuscan coastal town of Porto Ercole after being once again imprisoned en-route.

News quickly spread to Rome - the man whose works ‘attracted and ravished human sight’ like no other was dead. To the end, the only thing that could match the extraordinary drama of Caravaggio’s paintings was his own life.

Where to see it: Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano, Via Toledo 185. €5. Tues-Sun 11am-7pm. Closed Monday.