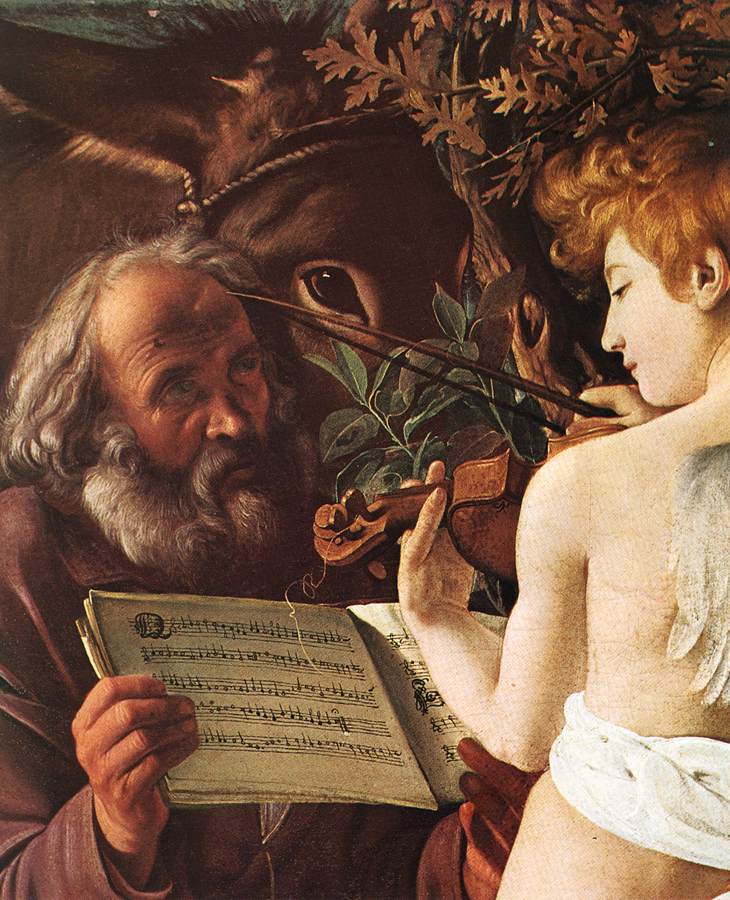

People often like to call it Caravaggio’s only real landscape. In the centre an angel, a delicately sensuous boy whose only nod to his divine formation is the pair of wings emerging from between his shoulder-blades, seems lost in the sounds he is conjuring out of a viola. A loosely tied white garment snakes around his otherwise naked body, a rather inadequate covering for this messenger from God.

Seated in front of him, an old man holds open a musical score for the angel/boy to read, his eyes fixed intently, even rapturously, on the divine musician’s face. The score has been identified as a contemporary composition based on the Old Testament Song of Songs, one of the most overtly romantic passages in all of Biblical literature. The refrain of this passage is like a great leitmotif for everything that is going on in this painting - ‘How beautiful you are, my beloved, you creature of bliss!’

Disguised by a few isolated leaves of foliage, we are maybe surprised to discern the face of a donkey right next to that of the old man, his huge wet eye looming disconcertingly out of the canvas. He looks outward at us, the only character in this scene even remotely aware of our visual intrusion. Half obscured by the angel’s right wing, a beautiful young mother cradles her contented child.

She seems set apart from the musical tableau before her, her head bowed and eyes closed in repose, her right arm fallen limply to the side. One would be forgiven for not immediately recognising her as Mary, for she is clothed in red rather than the deep blue that is the customary symbol of her exalted station.

The scene represented before us is the biblical story of the Rest on the Flight to Egypt, but Caravaggio hardly overemphasises the overtly religious theme. A few isolated rocks and scrubby plants in the foreground provide justification to the claims of landscape, but it seems a rather crucial element of that genre is missing here: the very concept of space itself.

Certainly there is a hint of sky visible in the background, and the merest suggestion of hills, but these more closely resemble the schematic friezes of stage scenery rather than the meticulously constructed and optically coherent settings of his great Renaissance forebears.

Caravaggio’s harnessing of space throughout his career is a fascinating aspect of his art. From the almost claustrophobic denial of space in which to move in works such as the Rest on the Flight to Egypt and The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew to the sheer excess of space, the dominance of the empty void in later works such as the Beheading of John the Baptist, spatiality in all its lack or excess plays a fundamentally constitutive role in our viewing experience. It is rarely if ever the harmonious framework which unifies the composition, but rather a figurative force in of itself.

The scene before us, we would have to conclude, is most certainly not a scene set in the ‘reality’ of space. Indeed, why should it be? The spaces of the biblical narratives are surely as much celestial and psychological as they are earthly. The four figures that comprise this tableau are pushed so close to the picture plane, so close to the viewer that such questions of spatial unity lose their validity. These incredibly poignant exchanges of humanity are all that matter, an arrested serenity in a narrative of flight and persecution.

The subtlety and beauty of these interactions display a side to the great artist all too frequently ignored. For those who accuse him of contributing little more to the history of art than shock value, a trip to the Doria-Pamphilj gallery in Rome should be obligatory. We are so far from the body-horror of Caravaggio’s Medusa or his Judith Beheading Holofernes that it is almost difficult to see them as springing from the same mind and the same brush.

Fascination with the life and work of Caravaggio seems to grow and grow, and thousands of pages of ink are spilled on him every passing year. The drama, violence and sensation of much of his oeuvre, in which it is so tantalising to see a reflection of his maverick life, will never fail to entertain us. But his capacity to produce such beautiful moments of quiet contemplation as this stunningly demonstrate that Caravaggio was no one-trick pony.

The stunning Doria Pamphilj gallery is one of the Eternal City’s most impressive showcases for Caravaggio’s art, and is one of the key stops on our Caravaggio in Rome tour. Follow in the footsteps of the madcap genius as he blazed a trail through late 16th-century Rome in the company of an expert art historian, and see for yourself why Caravaggio is widely regarded as one of the greatest painters in Italian art!