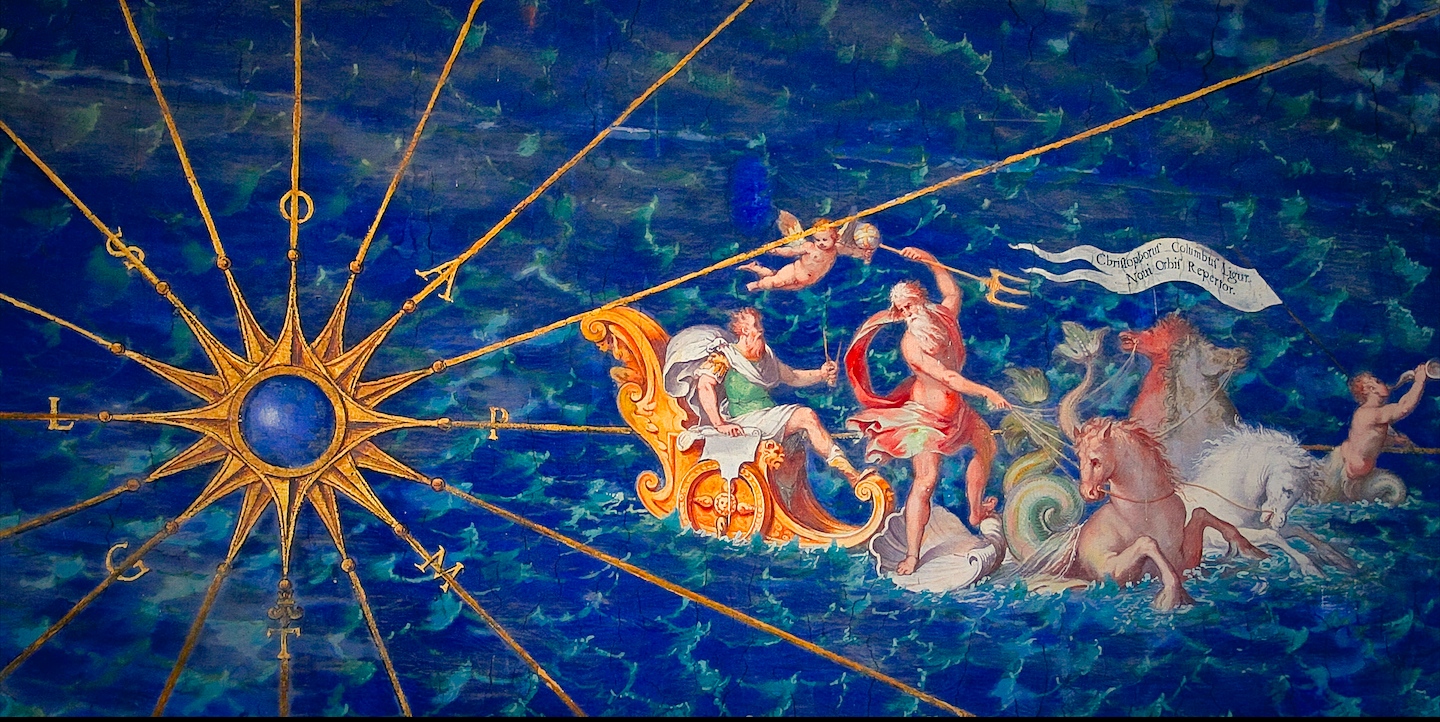

Some small details of artworks stop us in our tracks and demand our attention because they are so iconic. The trace contact between the hand of God and Adam in the Sistine Chapel that conjures humanity into existence, or the ambiguous smile playing about the lips of the Mona Lisa – once they catch your eye, it can be difficult to wrench yourself away. Sometimes though we do a double-take because we come across something so bizarre and unexpected that we have to look again – did I really just see that? At least that was my reaction when I first caught sight of Christopher Columbus in the Vatican Museum’s magnificent Hall of Maps, charging furiously across the Atlantic and towards the New World that would make him immortal in a chariot borne over the foamy waves by a team of sea-horses.

Despite often being rushed through by visitors beating a well-worn path to the Sistine Chapel, the vast, 120 metre long Hall of Maps is one of the most spectacular spaces in the Vatican museums and definitely worth a stop. Created in 1578 to document the vast extent of Pope Gregory XIII’s worldly dominion, the 40 enormous maps unfolding along its walls comprise one of the most ambitious attempts to chart the Italian peninsula ever attempted. Paying to have your territorial holdings painted on the walls of your palace was a common way for the great aristocrats of 16th-century Italy to flaunt their wealth, but Gregory took things to a whole new level: here every corner of the Italian peninsula is mapped in vivid Technicolor, along with all the islands in the Mediterranean and the French papal city of Avignon.

The Pope hired the mathematician and expert geographer Ignazio Danti to oversee the works, and a great team of some of the finest artists of their age worked flat out for three years to bring the amazing project to fruition. Pope Gregory was a man obsessed, threatening and bribing local officials all around Italy to share with him their private classified maps, and he invested mind-boggling sums in the commission. The result was the most detailed cartographic vision of Italy ever undertaken. Even in the days of Google Maps, 3-D mapping and street-view, these hand-painted gems can still take the breath away.

They were even kept up-to-date for a few hundred years - new roads were painted in as they were constructed, and topographies were adjusted to reflect new information about the courses of rivers and the heights of mountains. Along the walls of one side of the hall are the regions of western Italy leading to the Tyrrhenian coast, and along the other are the eastern regions bordering the Adriatic. As you walk through the gallery it’s as if you were striding down the Italian peninsula along the highest peaks of the Apennine mountain range that divides the country in two, looking this way and that for glimpses of each coast. The effect is pure magic.

The regions of Italy unfold in a colourful riot of green, blue and gold, each displaying an incredible grasp of topography: mountain ridges, meandering streams and tempestuous seas are all rendered with exceptional precision and artistry. The cities and towns of Renaissance Italy appear too in plans and perspectives worthy of a modern urban-planner. Venice twinkles charmingly in its lagoon as ships weave in and out of its innumerable islands, whilst the red-tiled roof of the Duomo rears impressively from Florence’s skyline. In Rome itself the Colosseum and St. Peter’s dominate the city, but here too is Palazzo Barberini, added to the map on its completion in 1622 by the Barberini pope Urban VIII looking to make his own mark on the maps. The influence of the Papacy is everywhere. Countless monasteries, basilicas and nunneries show off the political resonance of the cycle – there is no getting around the all-powerful Church, which has infiltrated every corner of the peninsula, and dominates its cities, towns and countryside.

The terrain traffics in time as well as space, and each map is animated by famous historical events: in modern-day Emilia Romagna we can see Julius Caesar making his fateful decision to cross the Rubicon with his army and plunge the empire into civil war in 49 BC. The island of Malta is depicted besieged by a Turkish fleet over a millennium later in 1565, whilst nearby Christian forces defeat the troops of the Ottoman Empire in a great naval battle off the coast of Lepanto in the Ionian sea in 1571, just a few years before the frescoes were painted.

But my favourite detail must be Columbus, dressed in the triumphant guise of a Roman emperor as he speeds away from Genoa and down the Ligurian coast. Compass grasped in his hand like his very own sceptre of power, he sits forward in his golden chariot as his white toga is whipped around his shoulders by a sea breeze. No less a figure than the sea-God Neptune himself guides its course, standing on a massive sea-shell lashed to the backs of four sea-horses thrashing the foamy sea with their hooves. A merman trumpets through a conch as he leads the way, carrying aloft a banner confirming the venerably bearded man’s identity: ‘Christopher Columbus of Liguria, Discoverer of the New World.’

More than just an exercise in mapmaking, the hall is an incredible virtual pilgrimage through the space-time of Italian history, an encyclopaedia of place intended to delight and awe its viewers. The more you look, the more amazing details you see. Keep your eyes peeled as you pass by, because you never know what new visual delight you might find concealed here. The Hall of Maps was intended by its creators as a 'luogo per spasseggiare,' or a place for unhurried wandering. As you make your way through the Vatican Museums take their advice - pause, and admire a sparkling vision of Italy depicted in wondrous microcosm.

Our Vatican tours delve into the easily ignored corners of the Vatican, bringing to life hidden histories concealed in plain sight. To discover the wonders of the Vatican Museums for yourself, join one of our expert-led itineraries!