Is your smile to tempt a lover, Mona Lisa,

Or is this your way to hide a broken heart?

Are you warm, are you real, Mona Lisa,

Or just a cold and lonely, lovely work of art?

The song made popular by Nat King Cole in 1951 compared a woman to the da Vinci masterpiece, a reference that everyone understood. Hardly surprising, since the portrait was hands-down the best-known painting in all the Earth. What many people didn’t realize then, and still don’t realize today, that in 1951 this had only been the case for about 50 years. In a 2016 article in Britain’s The Independent, the artwork was called "the best known, the most visited, the most written about, the most sung about, the most parodied work of art in the world." What had brought about this global notoriety? And who was this young woman with the enigmatic half-smile that has bewitched, bothered and bewildered viewers for more than half a millennium? Enquiring minds want to know!

Here we delve into a few things that you should know about her.

1. So who exactly was this young woman?

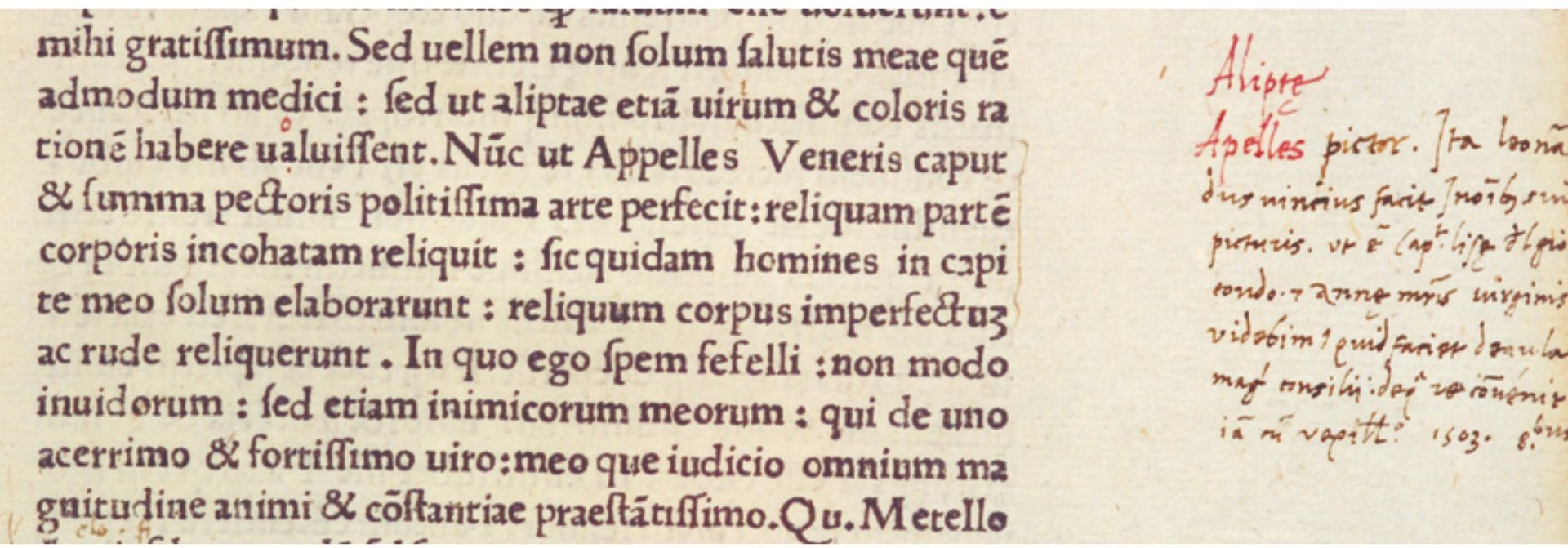

For centuries, the big money was on Lisa Gherardini, the wife of Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo. (In Italian, the piece is known as La Gioconda, in French as La Joconde, derived from her husband’s surname. “Mona” or “Monna” is the shortened form of “ma Donna” or “my Lady”.) The only known nearly contemporary source for this identification for centuries was the c. 1550 Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects by Giorgio Vasari. Until 2005, that is. This is when German Dr. Armin Schlechter discovered a hand-written comment in the margin of a manuscript held at the University of Heidelberg. The note was added in 1503 by a certain Agostino Vespucci, a Florentine chancellery official. It compares da Vinci to the 4th-century BCE Greek painter Apelles of Kos and states that the artist was in the process of completing a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo. This seems to have cleared up the controversy over the work’s dating as well as identifying with near absolute certainty the piece’s subject.

2. There were a number of other theories about Mona Lisa’s true identity.

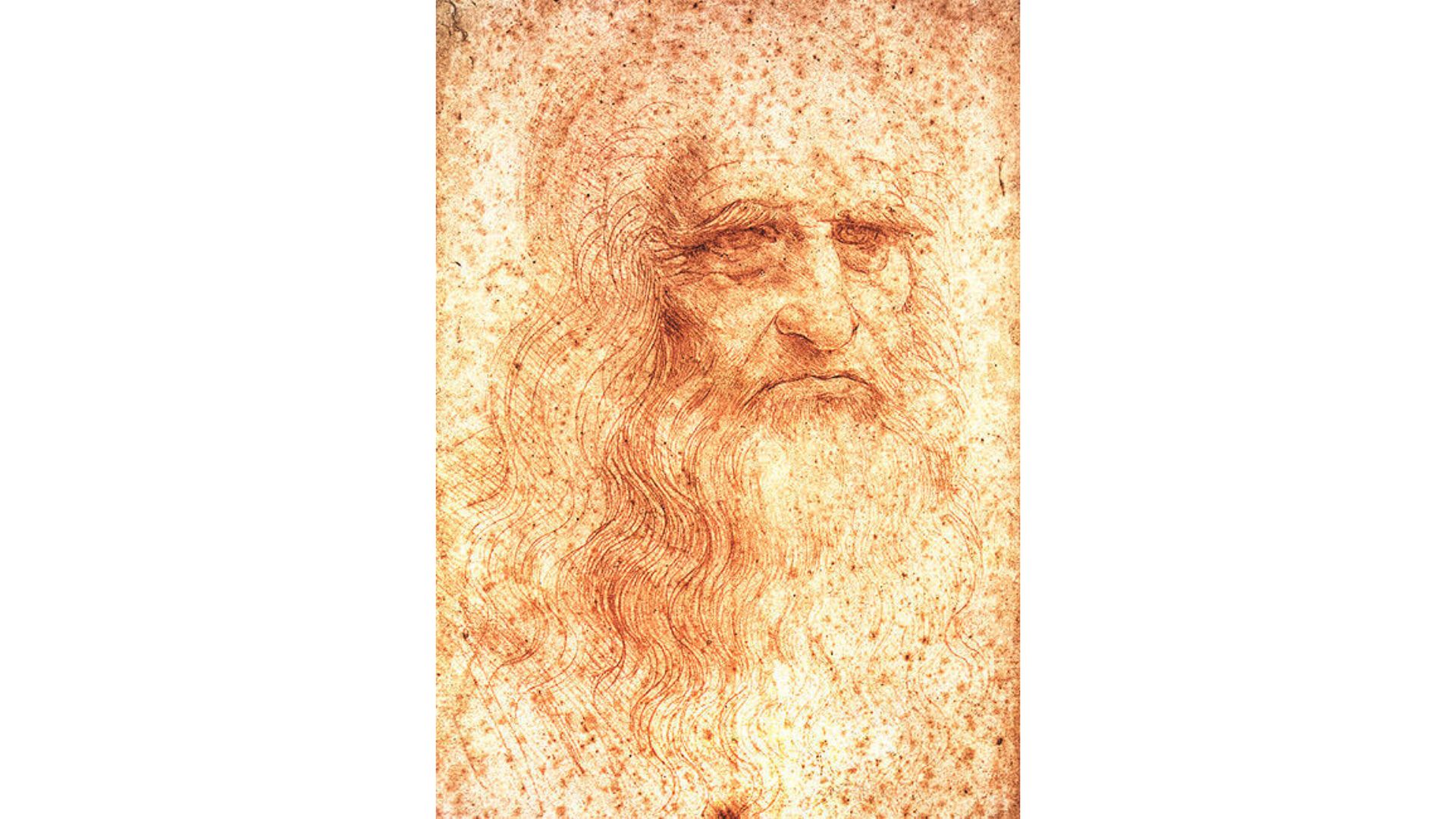

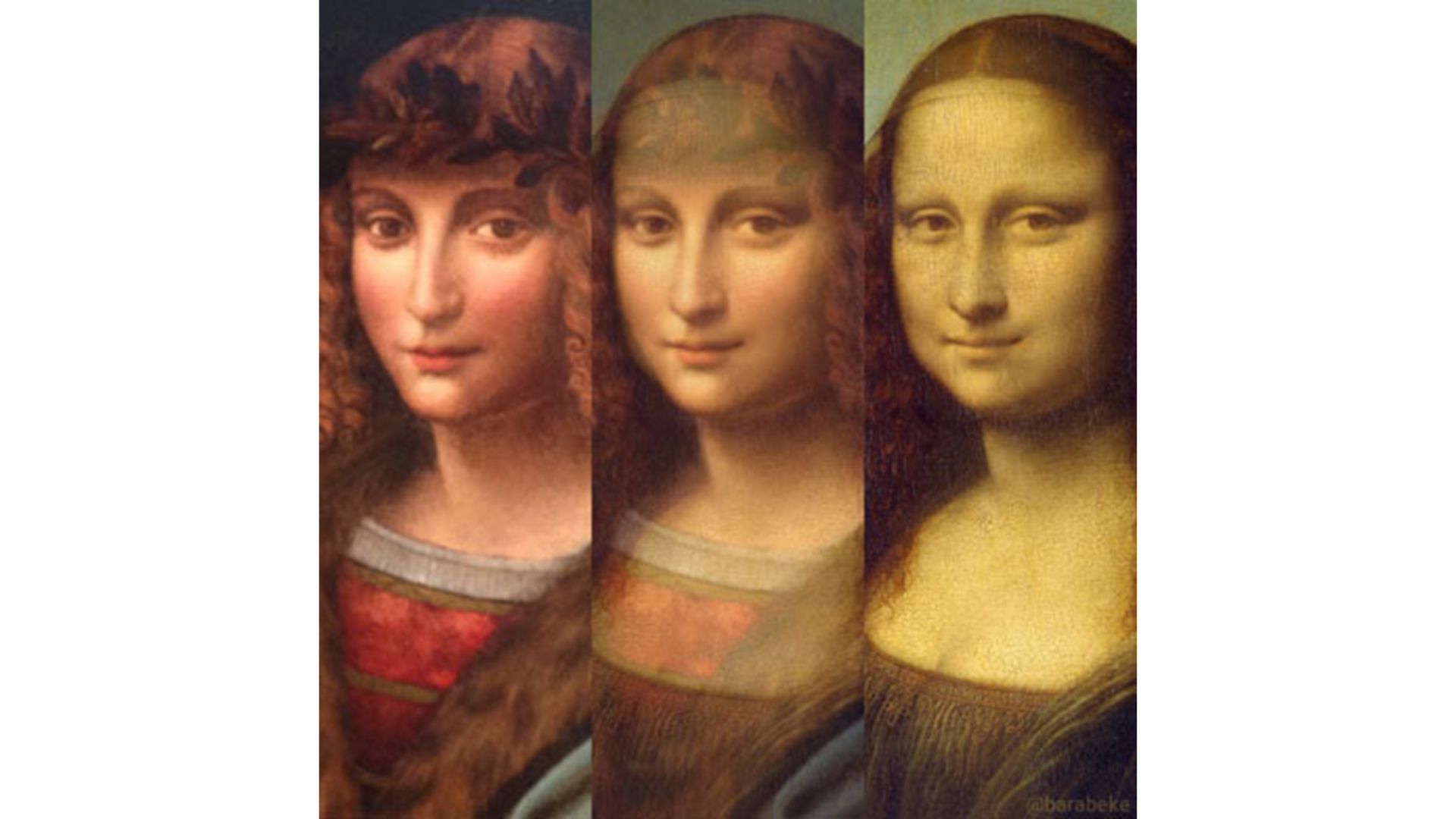

For those many centuries between da Vinci’ own lifetime and 2005, imaginations (and doctoral candidates working on their dissertations) had run wild. there was never a real model; this was no portrait of an actual individual but rather a piecing together of pieces and parts to form an image of the ideal woman. Others saw a cheeky self-portrait in drag, with evidence of eye shape, nose alignment, and other physical features to support the theory. We’ve always found this to be a little bizarre, given that the artist at the time – 1503 to 1506 – was between 51 and 54 years old, and frankly, he hadn’t aged well.

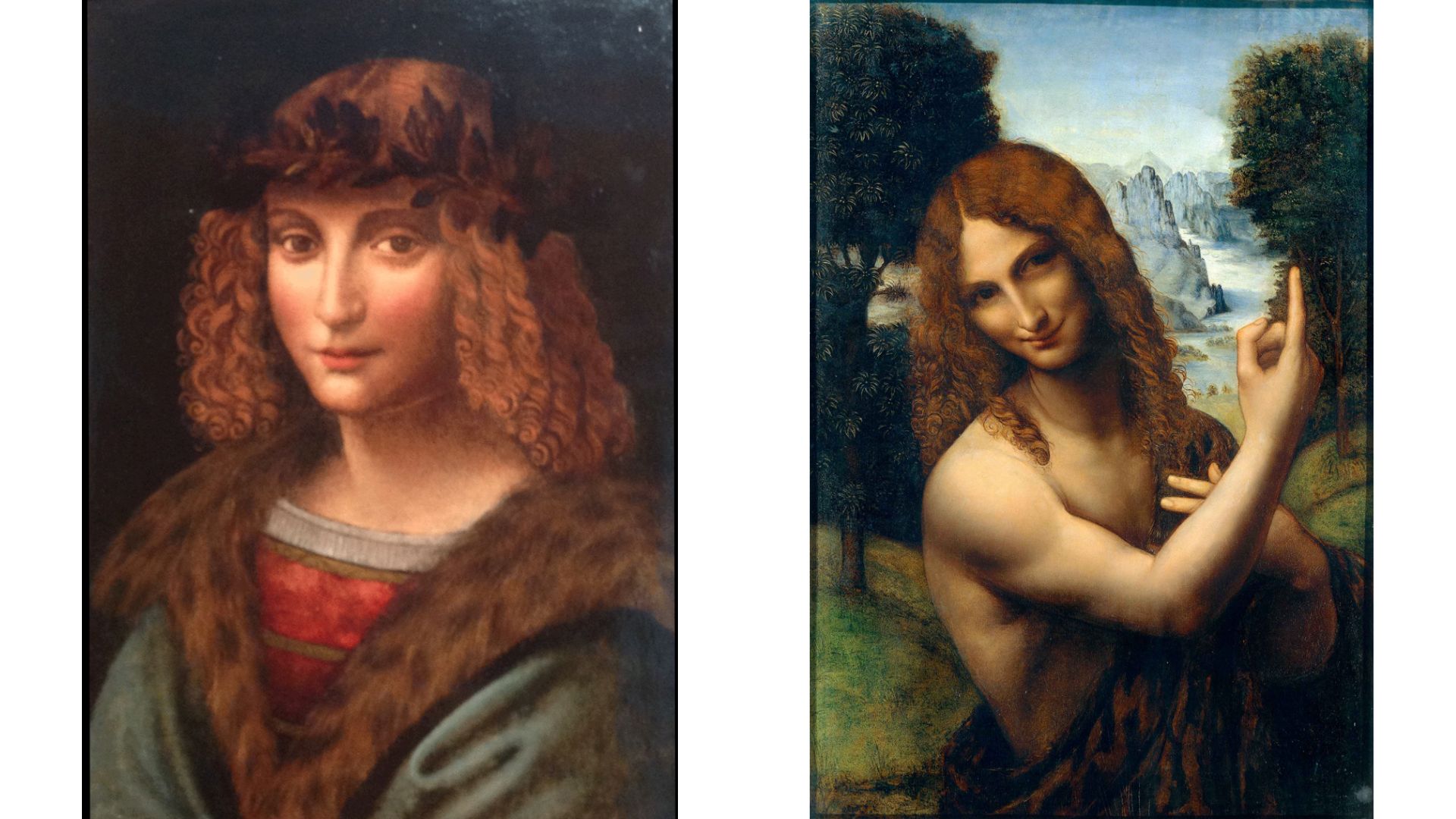

Perhaps the most titillating idea was that it was indeed a portrait of a man in drag, not of da Vinci himself but of one of his favored pupils. Gian Giacomo Caprotti, who would have been between 23 and 26 at the time. And what a beautiful young man he was! Leonardo’s appreciation of attractive young men was well known, even back in the day, so this theory had some traction for quite a long time.

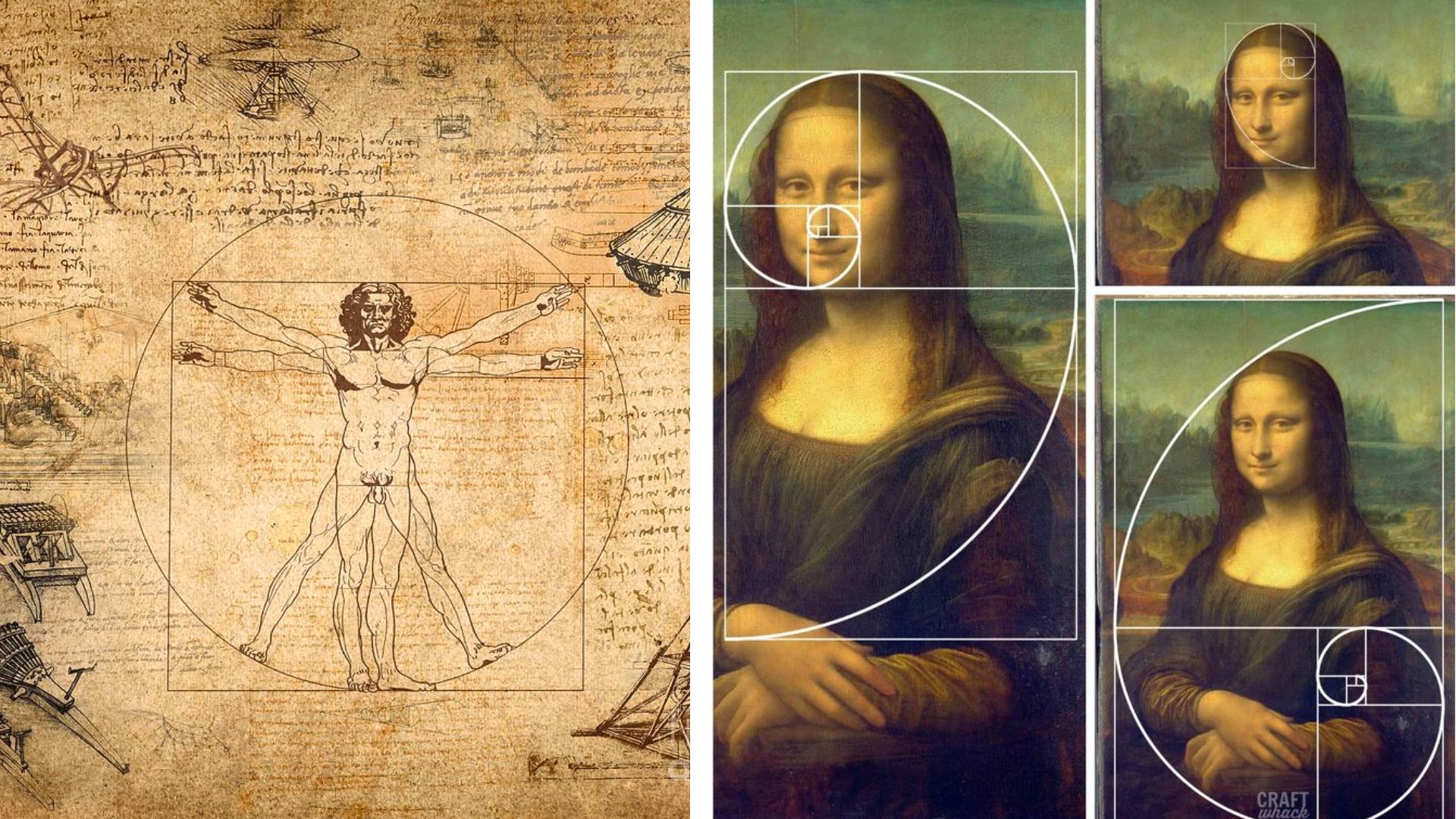

3. The portrait of Mona Lisa was also a brilliant exercise in perspective, proportion and mathematics.

Leonardo da Vinci was a man of particular genius with a broad range of interests and inspirations. As inventor, architect and artist, he was very familiar with his fellow Florentine Brunelleschi – the creator of the dumbfounding dome of their city’s cathedral – and his revival of the ancient theories and ideas of Vitruvius. Another child of the Florentine artistic and architectural world was Fra Angelico, who applied Brunelleschi’s mathematical concepts of perspective and proportion to painting. With the Mona Lisa, da Vinci is bringing the same principles he explored in The Vitruvian Man to portraiture, a stroke of genius on so many levels.

4. The Mona Lisa is certainly the most famous painting in the world, but only since the beginning of the 20th century.

For the 400 years since the great Renaissance master Raphael had painted it, his Transfiguration (1520) had held that title. As just one measure of this, when Napoleon ransacked Rome, stripping his favorite pieces from the walls of the Capitoline and the halls of the Vatican, he placed Raphael’s Transfiguration in a position of conspicuous honor in the Grand Gallery connecting the Louvre and Tuileries palaces.

Art academics and well-informed admirers were certainly aware of da Vinci’s portrait of the young Lisa Gherardini, as is attested by some rather purple prose by one Walter Pater in 1873: “Hers is the head upon which 'all the ends of the world are come.' The animalism of Greece, the lust of Rome, the mysticism of the middle age with its spiritual ambition and imaginative loves, the return of the Pagan world, the sins of the Borgias. She is older than the rocks amongst which she sits; like the vampire she has been dead many times.”

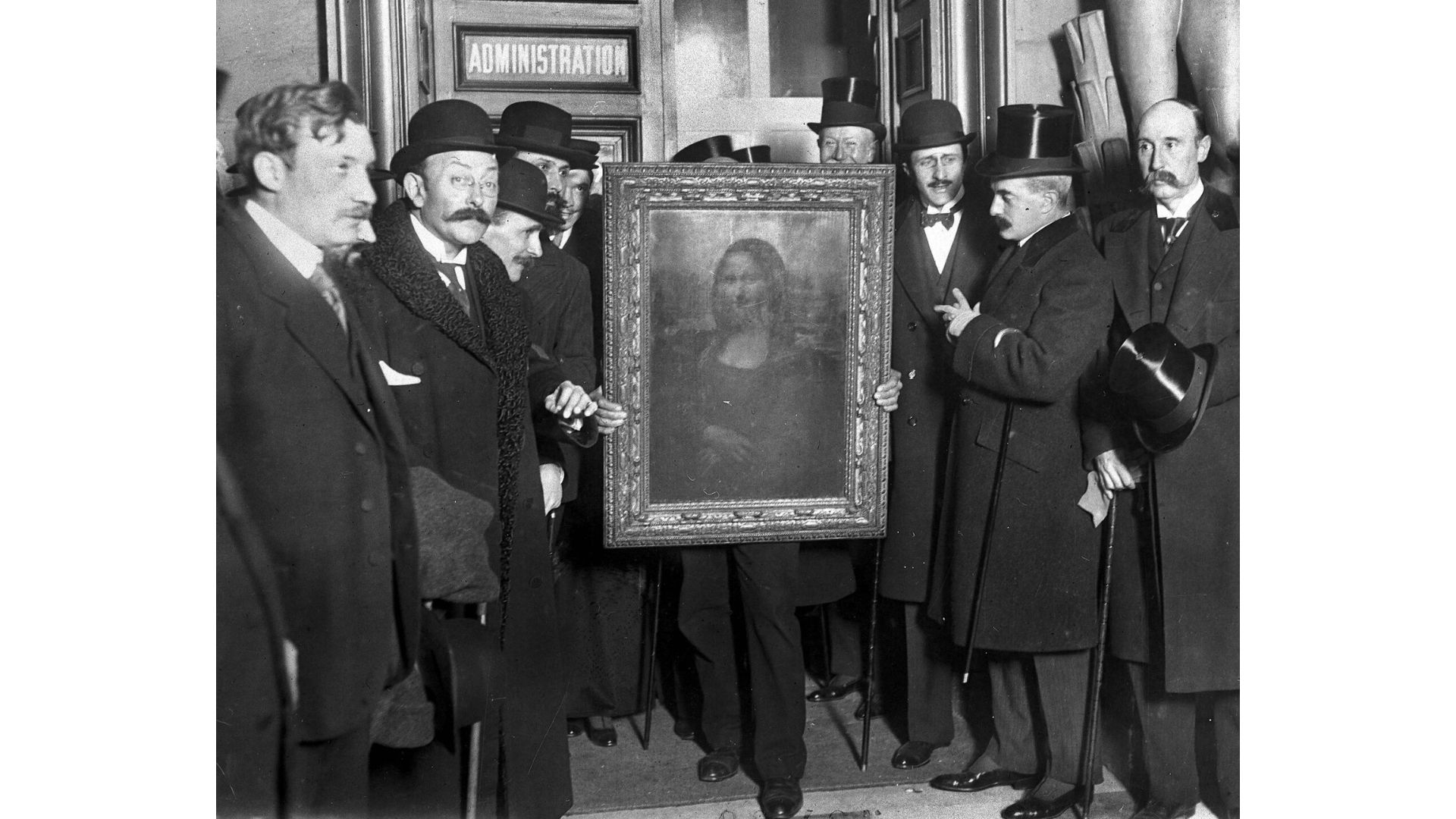

Upon da Vinci’s death, the portrait became part of the royal collections. With the defeat of Napoleon I in 1815, it was taken from above the emperor’s bed in the Tuileries Palace and hung on the walls of the newly-public Museum of the Louvre. It was there for all to see, but not many took much notice until she was stolen in 1911. It had been missing for two years when the culprit attempted to sell it to the Uffizzi Gallery in Florence. Vincenzo Peruggia, and Italian and apparently a bit of a patriot, believed – as did many at the time – that the Mona Lisa had been among the many artworks absconded with by Napoleon but had never made it back to Italy. In fact, da Vinci had brought the painting with him when he went to France in 1517, at the invitation (and with the generous financial stipend) of the young French king François I. It was the international coverage of the heist and the two-year relentless hunt for her that elevated her to the status as the world’s best-known painting.

5. The Louvre makes great efforts to educate the public, thanks to the Mona Lisa.

During the reign of Louis XVI, portions of the royal collections held in the Louvre Palace were made accessible to a restricted public. At the time of the French Revolution, the former royal palace was opened as the Central Museum for the Arts of the Republic. A visit to the museum was intended to be a didactic experience. Among the educated classes of the new Republic, it was felt that people who had for so long been subjects had to be taught how to be citizens, to be educated to become informed responsible voters. Art as education was the plan for the Louvre.

Among the items in the Louvre’s mission statement today is the following point: “To welcome the public, to increase the number of visitors to the museum, and to promote awareness of its collections, by any appropriate means.” When it was determined that about 80% of visitors (10 million a year) were there only to see the Mona Lisa, and that the same percentage of people who saw the Mona Lisa were disappointed by it, the Louvre’s administration could have decried the ignorance of the masses and warned that this is what was to be expected when you cast your pearls before the swine.

To their credit, they did precisely the opposite. They saw the failure as their own, failure in their mission to “promote awareness of its collections, by any appropriate means.” Simply put, they believed that they had thought too small, and they saw the desire on the part of the public to encounter the Mona Lisa tête-à-tête as their key to future success. In October 2019 the Mona Lisa returned to the large and newly-renovated Salle des Etats. Modifications had been made to help accommodate the up to 30,000 people per day who come to see her. A new virtual reality experience in another room plunges visitors into her 16th-century world and introduces them to her history in the half-millennium since. In 2022, the Louvre paired with the Grand Palais for an immersive and interactive experience that proved to be spectacularly successful.

In these and other ways, the Musée du Louvre is helping us all better understand the past, providing illumination for her future… and for ours.