In painting Cimabue thought he held the field, and now it's Giotto they acclaim - the former only keeps a shadowed fame.

- Dante, Purgatorio, Canto XI

If you have even a passing interest in the history of art, then the extraordinary Scrovegni Chapel in Padua is somewhere you need to visit at least once in your life. Considered perhaps the greatest landmark of the proto-Renaissance, the chapel was decorated all over with magnificent frescoes by Giotto in the opening years of the 14th century at the behest of local loan shark Enrico Scrovegni. Giotto’s place as one of history’s most important painters, responsible for ushering in a new understanding of the boundaries of pictorial expression, is beyond question - no story of art can be written without reckoning with the enormous influence and long shadow of the painter from the Tuscan hills. And in a career littered with masterpieces, the fresco cycle in Padua’s Scrovegni Chapel is his crowning achievement.

To celebrate the launch of our Best of Padua tour, this week on our blog we are taking an in-depth look at Giotto’s Arena Chapel frescoes. If you’re planning a trip to beautiful Padua, then make sure to read on to get a sense of what lies in store!

Who Commissioned the Scrovegni Chapel?

The magnificent chapel was commissioned by the wealthy Paduan banker Enrico Scrovegni as his private family chapel in the grounds of his lavish palace on the northern edge of the city. Enrico was one of the richest men in the city, heir to his father Reginaldo’s fortune made from money-lending (naturally, the loans demanded enormous rates of interest). Though widely practised in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, usury was a serious crime in the eyes of the Catholic Church, and Enrico’s father’s misdeeds in this regard were so grave that he found a place in hell in Dante’s Inferno just a few years later. Anxious to avoid a similar fate, Enrico determined to build a house to the glory of the Virgin Mary so sumptuous that it would in effect buy his way out of the flames that otherwise awaited him.

Although in theory dedicated to the mother of God, the scale and grandeur of the new chapel was such that many doubted the pious intent of Enrico, and to be sure the chapel was equally intended to be a lasting monument to the glorious memory of his own family. The monks living in the nearby Eremitani monastery complained bitterly about the grand new edifice dwarfing their long-standing dwellings, rightly suspecting that Scrovegni was more concerned with expiating his father’s sins than he was in humbly showing his reverence for the divine. Their complaints were to no avail: Scrovegni’s plans to expand the initial idea of a small family oratory into a fully-fledged church went full steam ahead, and in 1303 Enrico commissioned Giotto di Bondone to adorn the interior with an array of frescoes.

Why is the Scrovegni Chapel also known as the Arena Chapel?

The Scrovegni chapel is also widely known in the sources as the Arena Chapel (Capella dell’Arena) because the land that Enrico purchased next to his palace to build the chapel was originally the site of an ancient Roman amphitheatre, built during the reign of the Emperor Augustus. Today most of the ancient building has been destroyed, although part of the arena’s walls are still visible in the grounds of the Giardini dell’Arena.

Why is Giotto important in the history of art?

The frescoes Scrovegni commissioned from the Tuscan painter Giotto were to mark a turning point in the history of western art. Born around the year 1267, Giotto was the most important pupil of the late-medieval master Cimabue, and was in his prime by the time he came to Padua to fulfil the commission - perhaps the first celebrity artist, Giotto would soon be lauded by his illustrious contemporaries Dante Aligheri and Boccaccio in their poetry. Although contentious amongst scholars, it is likely that Giotto contributed to the decorations of the great church of Saint Francis in Assisi, alongside many of the most-renowned masters of the day, but the Scrovegni chapel would prove to be his most enduring masterpiece and the work that solidified his claim as the most important artist of the early Renaissance.

Giotto’s capacity to reduce his pictorial fields to the most essential aspects of the narrative ushered in a new language of visual storytelling; his figures seem convincingly 3-dimensional and move through spaces that are recognisably our own. Perhaps more even than these innovations, it is as a profound analyst of the inner psychological states of humankind that Giotto distinguishes himself - his characters think, act, and are moved in ways that we can still relate to, over 700 years later. It was this quest to isolate and represent the universal truths of humankind and the universe that would be carried forward and brought to new heights of complexity in the coming Renaissance.

What is depicted in the Scrovegni Chapel and how is it painted?

Giotto arrived in the Scrovegni chapel with a team of 40 assistants and a plan to cover every inch of the 700 square metres of wall space with vibrant frescoes. The fresco medium involves applying water-based pigment directly to a layer of still-wet plaster (known as the intonaco) in such a way that pigment and plaster form an impermeable chemical bond. It is this chemical bond that renders fresco one of art’s most durable mediums, and explains the incredible state of preservation of so many Renaissance masterpieces across Italy.

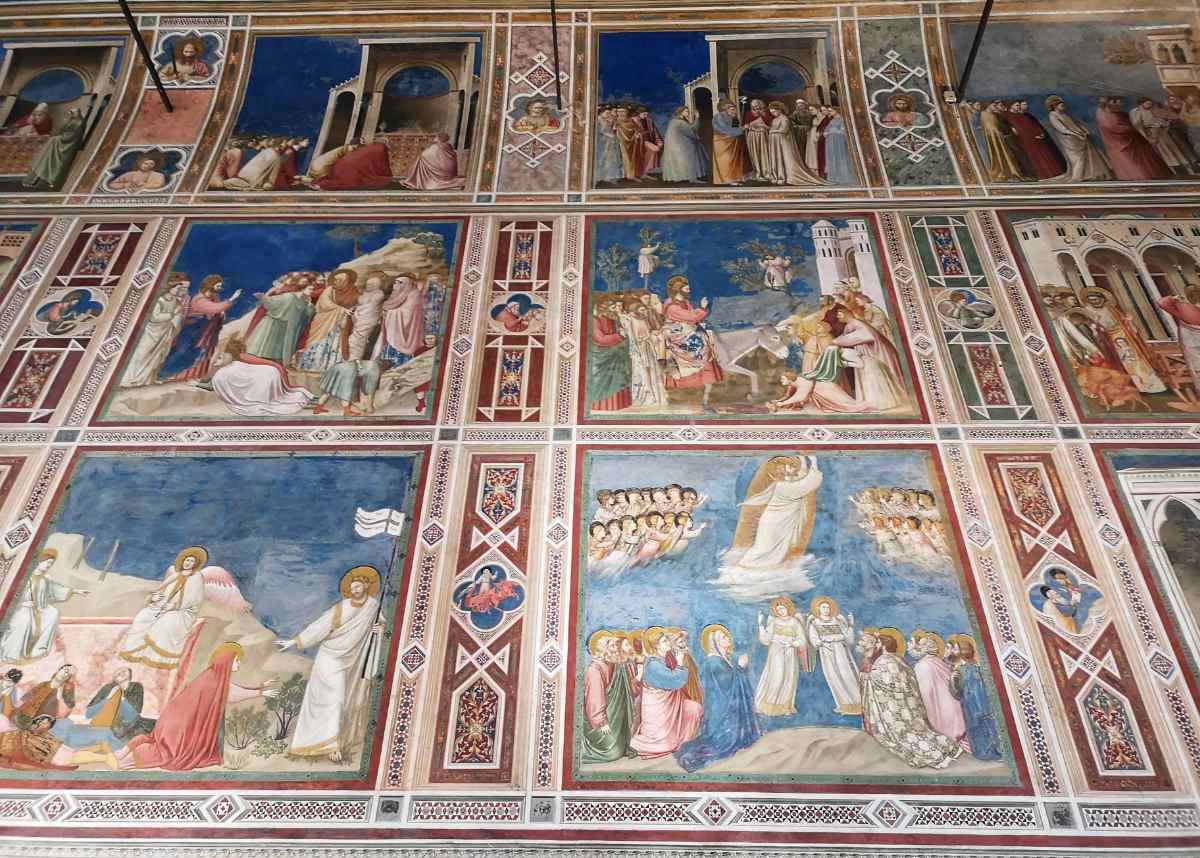

The particular exigencies of the fresco medium meant that only a small amount of wall could be painted each day: the work was divided up into giornate (Italian for ‘days’), signifying the amount of fresh plaster to be applied each day. Ultimately the work was divided into over 600 giornate - nearly two years of constant work - and encompassed 4 separate pictorial cycles: the Life of the Virgin and Life of Christ in three superimposed tiers running along the lateral walls surrounded by fictive frames of marble inlay and precious stones; personifications of the Cardinal Virtues and Vices below that, and a massive Last Judgement on the entrance wall, opposite the tomb of Enrico Scrovegni himself. A beautiful starry sky of midnight blue glitters down from the ceiling above.

The Life of the Virgin

As the Scrovegni chapel was officially dedicated to the Virgin of Charity, it’s only fitting that much of the decorations are given over to Mary. The upper register recounts the story of Mary’s parents Joachim and Anna, starting with their expulsion from the temple for their failure to bear a child. The story continues with the aged Anna’s miraculous pregnancy, Joachim’s dream of upcoming fatherhood, and the wonderful meeting of the parents-to-be under the arch of Jerusalem’s Golden Gate, where the two exchange an embrace of extraordinary tenderness and affection.

The next register continues the tale with the resulting Birth of the Virgin Mary in a narrow house, of whose interior we are privileged witnesses. Mary is presented at the temple and, reaching marrying age, receives prospective suitors. The elderly Joseph is the unlikely winner of Mary’s hand, and their nuptials take place to the strains of musicians in wonderfully detailed ensembles. The scenes from the Life of Mary conclude with the Annunciation, where the archangel Gabriel announces the news of the Virgin’s miraculous pregnancy, and Mary’s meeting with her cousin Elizabeth in the Visitation - another opportunity for Giotto to demonstrate his incomparable insight into human emotion in the women’s warm embrace.

The Life of Christ

The sacred tale reaches its climax in the parallel scenes from the Life of Christ that run along the lower halves of both of the chapel’s side walls in two superimposed tiers. No fewer than 23 frescoes take us through the story of Jesus in a great late-medieval comic strip, from the birth of the infant Christ in a rustic Bethlehem barn, where he is worshipped by oriental Magi carried from the east on exotic camels, through the family’s desperate flight from persecution into Egypt and Christ’s precocious disputation with the doctors of the church.

The sacred tale reaches its climax in the parallel scenes from the Life of Christ that run along the lower halves of both of the chapel’s side walls in two superimposed tiers. No fewer than 23 frescoes take us through the story of Jesus in a great late-medieval comic strip, from the birth of the infant Christ in a rustic Bethlehem barn, where he is worshipped by oriental Magi carried from the east on exotic camels, through the family’s desperate flight from persecution into Egypt and Christ’s precocious disputation with the doctors of the church.

A grown-up Christ begins to flex his divine muscles in subsequent scenes, turning water into wine after a planning disaster at the Wedding of Cana to the obvious delight of the guests, and raising a swaddled Lazarus from the dead as startled onlookers wrinkle their noses at the stench. Things hurtle on to the endgame we all know is coming as Judas betrays his prophet for a bag of silver, the apostles break bread for one last time during the Last Supper and Judas seals his devilish pact with a kiss. The exchange of gazes between the betrayer and the betrayed is one of the most powerful moments in all of art, the eyes of Judas and Jesus just inches apart.

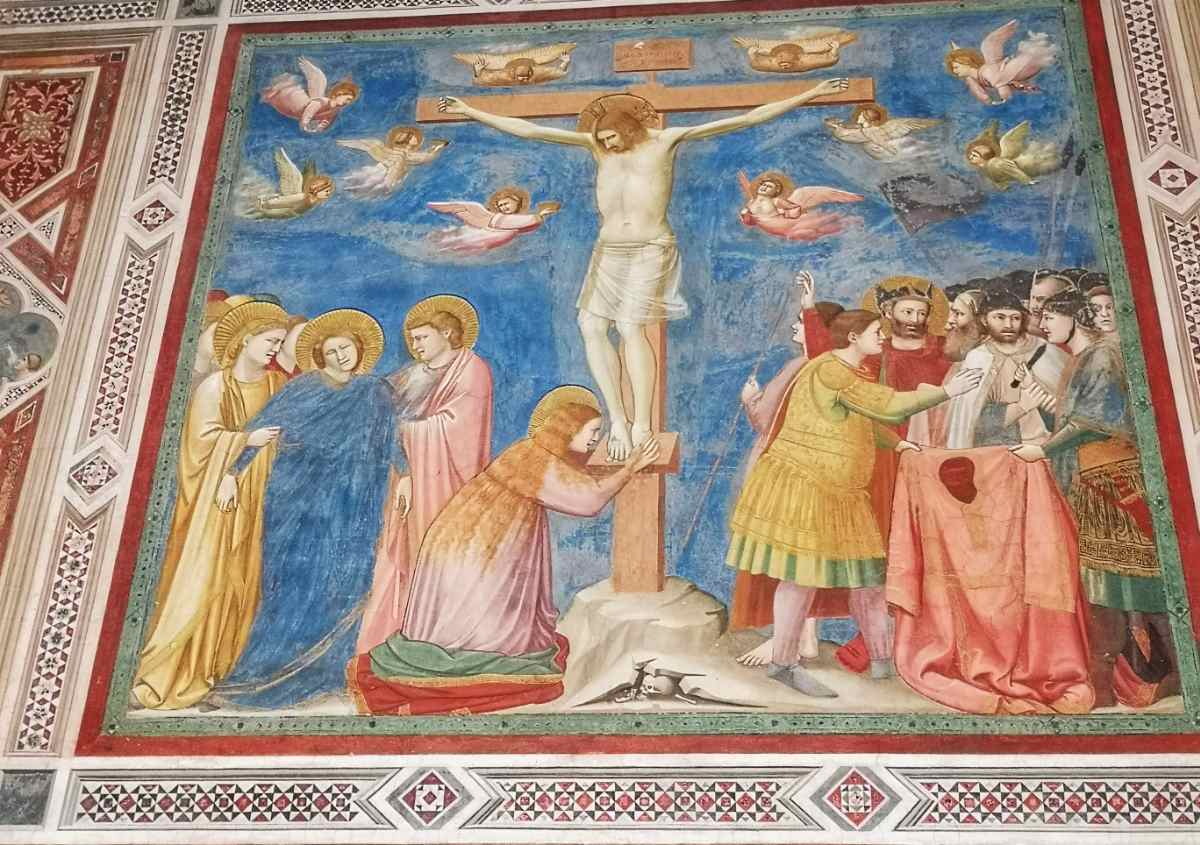

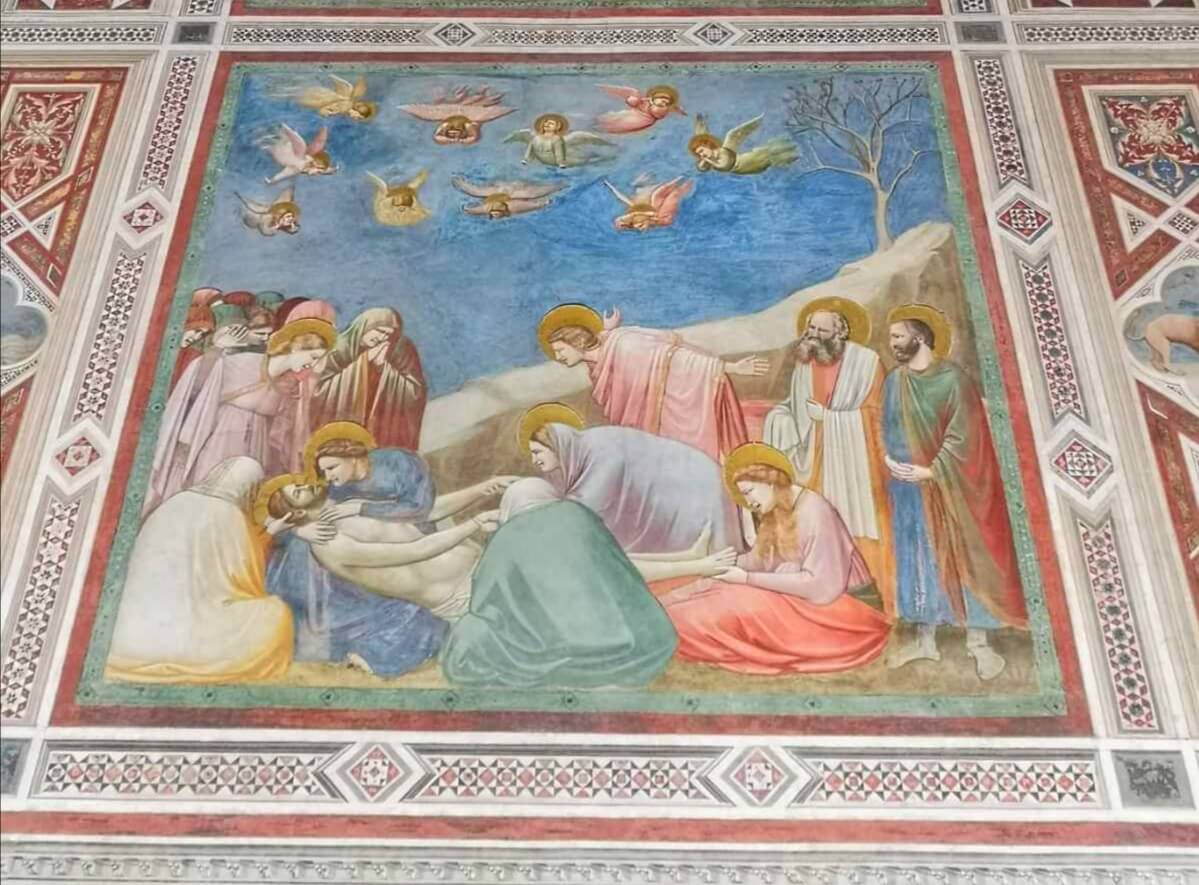

The final scenes from the Life of Christ cycle portray the events of the Passion and Resurrection. Jesus is brought before the judge Caiaphas, mocked and scourged by his tormentors, set on the road to Calvary carrying a cross and finally crucified on the hill of Golgotha as angels swirl in the aether to collect his holy blood, soldiers gamble for his clothes and a group of women (including the Virgin Mary) mourn his death, their faces pictures of inconsolable grief.

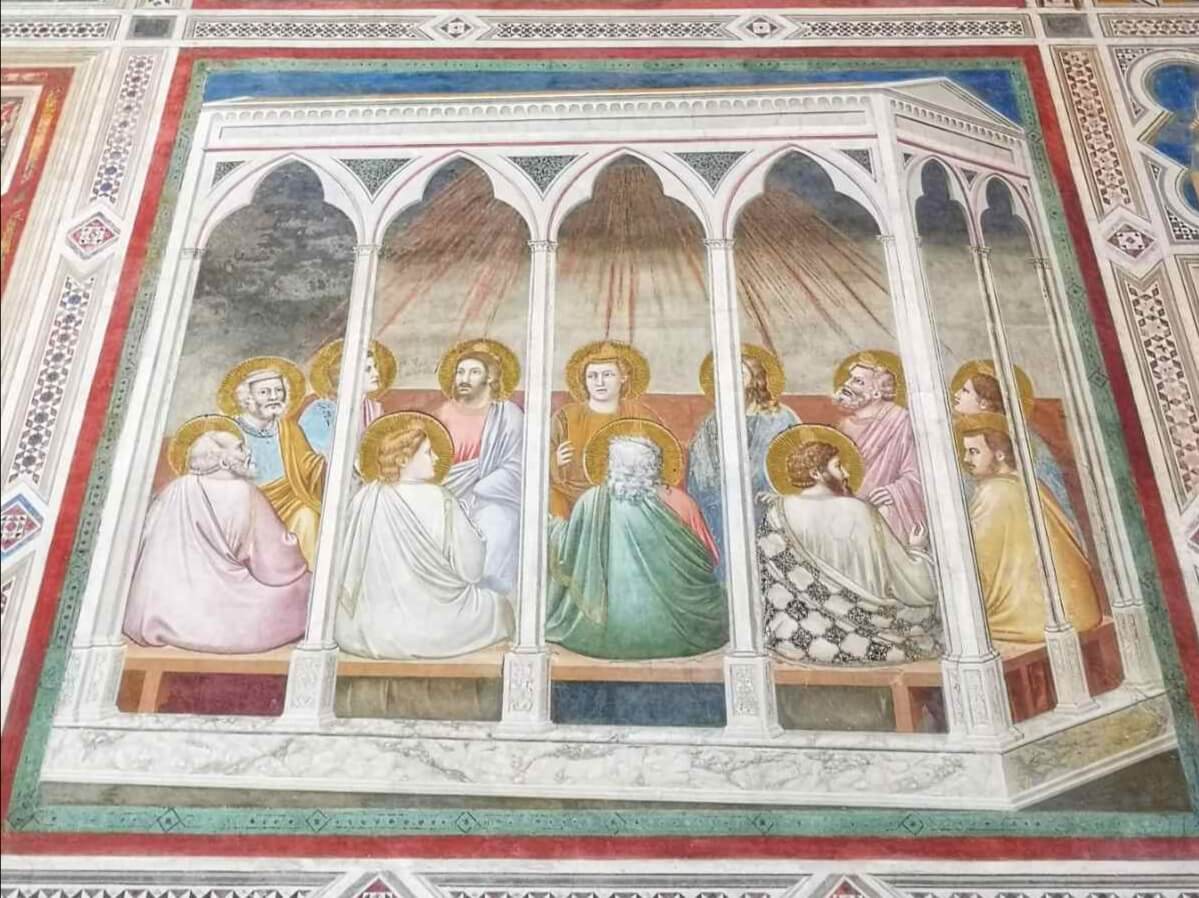

Christ isn’t down and out for long, though. After a short spell in the tomb he resurrects on Easter morning and rises to the celestial firmament in a spectacularly colourful display in the Ascension as rows of saints watch on. The cycle concludes with the Pentecost, where the Holy Spirit descends on the dumbstruck apostles in a beautiful Gothic arcade. Christ’s disciples will spread the word of God, setting the subsequent story of Christianity into motion.

The Last Judgement

Dominating the western wall of the chapel is a massive fresco depicting the Last Judgement, a traditional iconographic choice for the inner side of a church’s entrance wall. At the centre a massive judging Christ is seated in a glowing mandorla, flanked either side by severe seated apostles as rows of angels watch the drama from the safety of heaven above. The real action happens below, where a horrifying Satan is seated on a dragon as rivers of fire ferry desperate naked figures ever downwards.

Grabbing fistfuls of the damned souls in his dreadful claws, the devil devours them and excretes them into the deepest pits of hell. All around his winged minions subject the damned to every manner of atrocity imaginable, from sawing in two to hanging by hair and tongues, in an echo (or foreshadowing) of Dante’s near-contemporary vision of hell. This is the medieval imagination at its most terrifying, and Giotto is at the height of his dramatic powers.

The Virtues and the Vices

The lowest register of paintings along the dado of the chapel’s side walls eschews the narrative fictions of the rest of the decorations, depicting instead a series of illusionistic marble statues (a monochrome medium known as grisaille) that represent personifications of the virtues and the vices according to Medieval Christian theology. The three Theological virtues of Faith, Hope and Charity line up alongside the four Cardinal virtues of Justice, Prudence, Fortitude and Temperance. Flanking them across the space of the chapel are their dark doubles: the seven vices (not, in this case, the traditional seven deadly sins, but rather vices that directly correspond to the virtues opposite in a dualistic schema): Foolishness, Inconstancy, Wrath, Injustice, Infidelity, Envy and Desperation.

Amongst the vices, look out for Foolishness who wears the getup of a court jester, and Inconstancy sliding down a slippery slope. Wrath rends her garments in rage, while Injustice sits astride a dilapidated throne. Blind Infidelity is about to be consumed by flames, while Envy grasps a sack of money as her tongue sprouts into a serpent and the fires of envy lick at her feet. The tale of misguided woe ends in the terrible image of Desperation, who hangs herself.

The Virtues by contrast show a different path, one towards enlightenment and salvation. Sober Prudence is the image of restraint, while Fortitude is a powerful female warrior. Temperance exudes a measured calm in contrast to Wrath’s blind anger, while Justice balances right and wrong with a weighing scales. Faith carries a cross, and Charity a cornucopia of superabundance. Finally, staring down the tragic image of Desperation is Hope, who flies upwards towards heaven and an awaiting celestial crown.

The merry dance of virtue and vice offered a dominant explanatory principle for the cosmos in the Middle Ages, and they were frequently represented in contemporary decorations - but rarely with as much expressionism and vigour as at the Scrovegni Chapel.

How to Visit the Scrovegni Chapel

Padua is located just half an hour's train ride from Venice, and makes for the perfect day trip from Venice. The Scrovegni chapel is open daily from 9 AM to 7 PM all year round. Advance reservations are compulsory, and can be made via the Chapel’s official website. You must book your ticket at least one day in advance of your visit. At time of writing tickets cost €14 for adults and €5 for children under 17 and university students. The ticket price includes entrance to the nearby Musei Civici degli Eremitani (closed on Mondays).

The ticket office is located at the entrance to the Eremitani Museums, where you can collect your pre-booked ticket. Make sure to arrive in advance of your entrance time.

If you’d like to visit the Scrovegni chapel in the company of an expert guide, Through Eternity’s Best of Padua tour includes a visit to the Scrovegni chapel. We’ll also take care of all tickets and reservations in advance. Check out our Best of Padua tour here.