When you think of the splendid architecture that sparkles from every corner of the Eternal City, certain well-worn images inevitably spring to mind. Magnificent ancient temples, their ruined marble columns slowly crumbling to dust; airy Renaissance palaces, walls covered from floor to ceiling with impossibly elegant frescoes of cavorting gods and men; massive Baroque churches studded with gold and jewels, their domes seeming to defy the laws of physics as they soar into the sky. But scratch the surface a little more deeply, and you’ll soon find that the Roman skyline is about a lot more than the Colosseum and St. Peter’s basilica.

Unless you’re a clued-in architecture buff, it’s a lot less likely that you’ll be familiar with Rome’s modernist architectural heritage. And for good reason: the great flowering of architectural modernism in the Eternal City coincided with the inexorable rise of Italian fascism in the 1930s, and the major monuments of the period are inextricably linked to the cult of the totalitarian regime’s absolute leader – Benito Mussolini. Recognising that the iconic marble architecture of ancient Rome had propagandistically projected an enduring image of the empire’s imperial bona-fides, at the height of his power Mussolini decided that he too would harness the symbolic power of architectural form to give dramatic material form to his vision of a revitalised Italian empire united under fascism’s inhuman banner.

It was in the city’s southern outskirts that his plans reached their fullest expression, in what’s now known as the EUR quarter (short for Esposizione Universale Roma). Monumental, stark and strikingly out of touch with the Rome of the popular imagination, EUR’s hyper-rationalist architecture is a must-see for anyone with even a passing interest in modern architecture or the uncomfortable legacy of Fascism in the Eternal city. Read on for our guide to the sights you need to see.

Table of contents

- Genesis: The 1942 World’s Fair

- What to See in EUR

- Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana (Square Colosseum)

- Basilica dei Santi Pietro e Paolo

- Palazzo degli Uffici dell'Ente Autonomo

- Palazzo dello Sport (Palalottomatica)

- Palazzo dei Congressi

- Palazzo dell’INPS

- EUR’s Museums

- The Cloud

- How to get to EUR

The 1942 World’s Fair

In 1936, Italy’s fascist regime was successful in their application to host the planned 1942 World Exhibition in Rome. The driving force of the plan was the governor of Rome Giuseppe Bottai, but Mussolini was immediately enthusiastic - for him, the bombastic event would be a crowning commemoration celebrating 20 years of fascist rule in the country.

Taking the opportunity to display the perceived cultural, technical and architectural sophistication of the regime, the architect Marcello Piacentini was drafted in to design an entirely new quarter of the city that, in addition to hosting the pavilions of the fair, would double as a state-of-the-art business and residential district unlike anything Rome had seen before.

The site of the ambitious development was to be about 3 miles south of the city’s ancient walls, hemmed in by the Tiber’s eastern bank. Following Mussolini’s requirements to the later, the carefully planned urban design of the EUR quarter was monumental, geometric and rational, with strictly classical forms modulated by the latest ideals of an ultra-modernist minimalist chic – all presenting a meticulously curated vision of the apparently enlightened ideals of the golden age fascism was promising to bring the Italian people.

But such dreams of grandeur proved fleeting in the extreme: due to the outbreak of World War II the world exhibition never actually took place, and the unfinished quarter languished as a symbol of the failed hubris of Italian fascism until the mid 1950s when the post-war government completed the development under the aegis of a new generation of architects, moving a number of civic agencies and museums into the oversized unoccupied buildings.

60 years later EUR is a buzzing place of business during the week, but retains a strangely otherworldly air, especially at the weekends, when it’s something of a ghost-town - like a window into a future world that (thankfully) never came to be. Fascinating but eerily disquieting, the great Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni cast EUR’s echoing halls, deserted boulevards and immense futurist statues as a cipher for existential angst in his 1962 masterpiece l’Eclisse for good reason.

What to See in EUR

Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana (the Square Colosseum), Viale della Civiltà del Lavoro, 50

The most famous building in EUR and instantly recognisable symbol of the quarter, the striking structure known to most as the Square Colosseum was conceived of as the dramatic centrepiece of the abortive Rome World’s Fair. The extravagant and somewhat debauched palace is a bizarre cubist take on ancient Rome’s most famous monument; but where the Colosseum boasts three levels of arches framed by the classical orders, here the 60 metre tall structure is divided into 6 stories of 9 unadorned arched windows on each side – a narcissistic reference to the number of letters in the self-styled Duce’s name.

While the shape of the palazzo inevitably recalls the Colosseum, the sculptures that stand guard over its four corners instead pay homage to another monument of the ancient city’s heritage – the massive statue of the mythological Dioscuri horsemen Castor and Pollux on the Quirinal hill. Framed by the arches of the lowest level are personifications of the arts and sciences in whose legacy the Italian state was particularly proud, from philosophy to commerce, chemistry to navigation. As if to underline the point, an inscription at the top of each facade trumpets Italy’s status as ‘a nation of poets and artists, of heroes and saints, of thinkers, scientists, explorers and travellers.’ These days the building’s unsavoury origins have been left behind, with fascism slickly swapped for fashion – in 2015 luxury fashion house Fendi adopted the Square Colosseum as their global headquarters.

Basilica dei Santi Pietro e Paolo, Piazzale Santi Pietro e Paolo

At the highest point in EUR, the quarter’s flagship modernist church lords it over the surrounding terrain. Reached by a long ramp of shallow steps inlaid with coloured marbles and flanked by Roman cypresses framing twin statues of Saints Peter and Paul, the cubist Basilica is the masterpiece of the architect Arnaldo Foschini - who had also collaborated with Piacentini on Mussolini’s plan to modernise Rome’s historic university, La Sapienza.

Initially planned as a possible solution for Mussolini’s future mausoleum (although the narcissistic autocrat also harboured ambitions of being interred in the ancient Mausoleum of Augustus in central Rome), work began in 1938 but was abandoned during the war, during which time the half-built basilica was site of fierce fighting after German troops occupied Rome in 1943. The project gained new life after the war ended, and the basilica was finally completed in 1955 - when it was dedicated to the patron saints of Rome rather than the deposed despot.

The massive church is a masterpiece of modern architecture: designed on the plan of a Greek square cross (a nod to Michelangelo’s unrealised floor-plan for St. Peter’s), the reinforced concrete structure takes the shape of a great cube surmounted by an enormous central dome – the third largest in the entire city. Inside, imposing modernist mosaics glower own from the walls, with the father-son partnership of Attilio and Sergio Selva providing the highlight of Christ in Glory over the altar.

Palazzo degli Uffici, Viale della Civiltà del Lavoro

The first building to be completed under the auspices of the EUR project was designed by Gaetano Minnucci to house the exhibition’s offices and bureaucratic centre. Characterised by a severe portico supported by elegant modernist pillers, the façade is topped with an inscription celebrating the expansion of the city towards the sea under the fascist regime. The real highlights of the palazzo come in the form of the classically inspired mosaics and sculptures that decorate it, however.

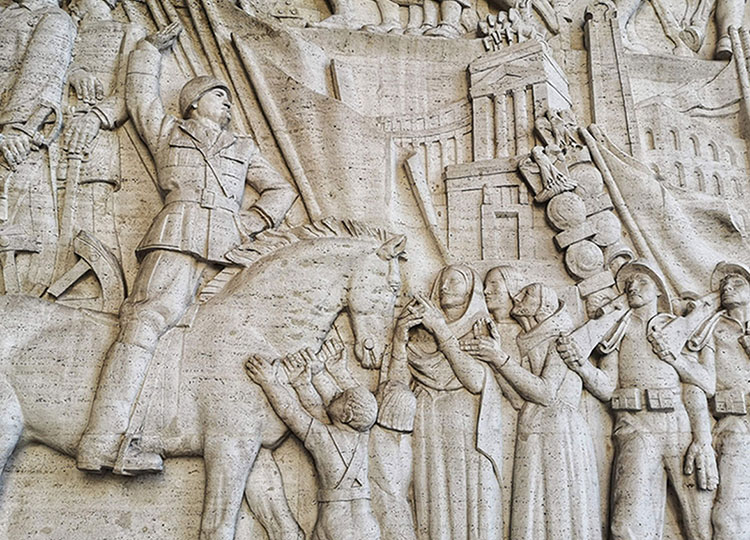

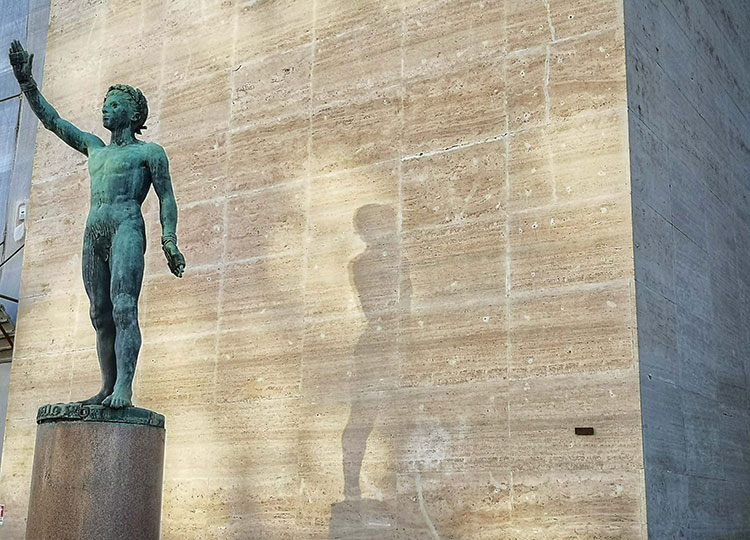

Look out in particular for Publio Morbiducci’s relief sculpture just to the right of the entrance depicting the story of Rome through its engineering projects, including motifs inspired by the decorations of the Arch of Titus and Trajan’s Column. Mussolini himself egotistically rubs shoulders with Rome’s ancient emperors, gesticulating furiously on horseback before genuflecting crowds as fascist architecture springs up all around him. Disturbingly given the future course of events, just above Mussolini is a copy of a relief from the Arch of Titus representing Rome’s legions making off with treasure from the temple of Jerusalem after the ruthless sack of the city and enslavement of its Jewish population in 70 AD. Don’t miss Italo Griselli’s elegant if problematic sculpture Il Genio dello Sport nearby, in which a young athlete raises his arm in an unmistakeably fascist salute.

Palazzo dello Sport (PalaLottomatica), Piazzale dello Sport

After the failure of the plans for the 1942 World’s Fair, it was the awarding of another major event to the Italian capital that gave the final impetus for EUR’s development: the 1960 Summer Olympics. At the heart of the preparations for the 17th modern Olympiad was the futuristic Palazzo dello Sport overlooking EUR’s artificial lake (home to the rowing at the Olympics) like some alien mothership: one of the highlights of Italian rationalist architecture, the building was designed in the form of a massive circle of glass and concrete by the architect Marcello Piacentini and engineer Luigi Nervi.

With an area of 20,000 m2 and a capacity of over 16,000, it’s one of the most impressive indoor arenas in Europe - these days the Palazzo is known as the PalaLottomatica, and plays regular host to sports, music events and political conventions. Don’t forget to take a stroll around the lake whilst you’re here too: a city hotspot for water-sports, in early Spring the cherry trees surrounding the water (a gift from the city of Tokyo) burst into bloom, making this one of the most peaceful spots in Rome to partake in the Italian ritual of the passeggiata.

Palazzo dei Congressi, Piazza John Fitzgerald Kennedy, 1

If the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana took its cue from the ancient Colosseum, the nearby Palazzo dei Congressi might be thought of as a rationalist update of antiquity’s most venerable temple - the Pantheon. Indeed, the proportions of the central Salone dei Ricevimenti are designed to be capable of exactly containing Rome’s temple of all the gods within.

Designed by Adalberto Libera for the Universal Exhibition but again abandoned because of the war, the huge structure was only completed in 1954 and made its bow during the 1960 Olympics when it hosted the fencing competition. The building is a virtuoso combination of classicising form and the clean, minimalist lines of rationalist architecture: an imposing rectangular block of reinforced concrete is topped by a squat geometric dome, whilst the palace’s spectacular façade is made up of a wide loggia of slender modernist columns. The Palazzo is only open when events are being held, but if you do manage to make your way inside look out for the modernist artworks that decorate the halls. Of particular note are Achille Funi’s futurist take on the origins of Rome in mosaic and Gino Severini’s massive mural in the atrium depicting agricultural processes and the four seasons.

Palazzo dell’INPS, Piazzale Nazioni Unite

Another rationalist take on the architectural riches of antiquity, the headquarters of the INPS (part of the Italian labour ministry), boasts an unimpeachable provenance – the sweeping semi-circular façade with a lower bay of openings surmounted by two rows of curving colonnades is a futuristic update of ancient Trajan’s Market, a landmark of classical design that looks over the Imperial forums in central Rome. Keep your eye out for the reliefs decorating the building by Mirko Basaldella, which pay homage to the great maritime republics of Italian history in a classicising style. Across the street a near identical exedra faces the Palazzo dell’INPS, creating a perfect symmetrical mirroring.

EUR’s Museums

EUR is also home to some of Rome’s most interesting and (sadly) little visited alternative museums. The entrance to the museum quarter is heralded by Arturo Dazzi’s modernist obelisk dedicated to radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi in the centre of the eponymous piazza (originally known as Piazza Imperiale). Surrounding the piazza on all sides are the museums: Rome’s Museum of the Middle Ages, Museum of Oriental Art and Museum of Folk Arts and Traditions are all here.

Housed in the Palazzo delle Scienze, meanwhile, the Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico is worth a visit for the rich collection of African and Asian art and artefacts collected by the eccentric 17th-century Jesuit academic and traveller Athanasius Kirchner and originally housed n the Collegio Romano, providing a great insight into the global reach of early modern Rome. Although currently closed for seemingly interminable restorations, the nearby Museo della Civiltà Romana is home to one of the most important exhibits in the city for understanding the vast urban scope of ancient Rome – a reconstruction of the urbs as it was in the 4th century A.D on a scale of 1:250. Sculptural casts, dioramas and a copy of the reliefs that twist up Trajan’s Column complete the visit.

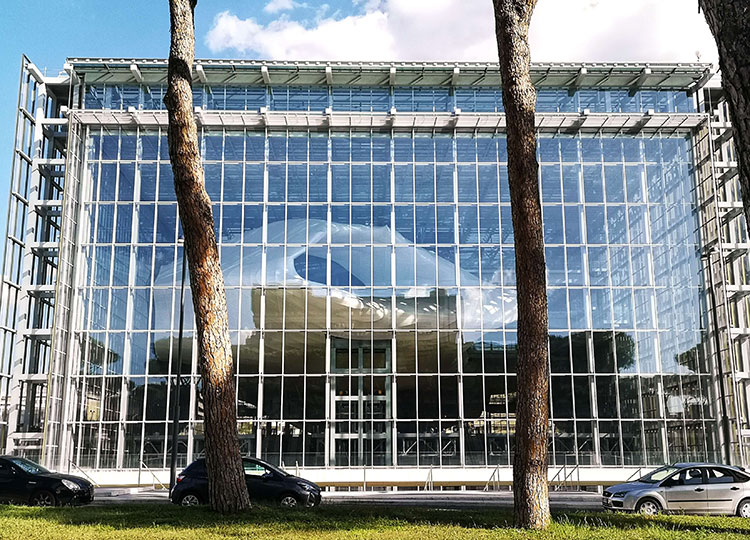

The Cloud, Viale Asia, 40

The latest stage in EUR’s continuing evolution, the bombastic convention centre designed by Italian starchitect Massimiliano Fuksas was finally completed in 2016. The largest new build in Rome for half a century, the EUR Convention Centre is communally known as The Cloud (La Nuvola) thanks to the distinctive undulating shape of its central fibre-glass cocoon. Whilst in keeping with the rationalist ideals of the quarter through its clean lines and futuristic materials, the Cloud also adds some Baroque pizzazz to the severe architectural landscape - its sinuous curves and sculptural use of space are a lot more playful than EUR’s unforgiving geometry. As Fuksas himself stated, the building has two sets of inspirations: ‘the rigid geometry of the EUR on one side and then the baroque Rome, the organic Rome, the Rome of Borromini’ on the other.

The Cloud has its share of detractors too, though. Completed only after a difficult 20 year genesis that included planning controversies and corruption allegations, and arriving over budget at an eye-watering cost of around €353 million, many are convinced that the EUR behemoth was an unnecessary vanity project. The Cloud is periodically open for major expos and conventions that are open to the public.

How to get to EUR

The quickest way to reach EUR from the city centre is by hopping on the B line of the metro heading south towards the Laurentina terminus. Get off at EUR Fermi, and you’ll be within easy walking distance of all the sites mentioned in this guide. You can also take any of the busses heading along via Cristoforo Colombo (lines 30, 174 and 714) – arriving this way, you’ll get a vivid sense of how EUR was originally intended to be approached, when the artery was known as via Imperiale. If possible, EUR is best visited at the weekend when the business people are gone and the streets are pregnant with the metaphysical unease that so fascinated Antonioni more than half a century ago.