Florence might be justly regarded as the cradle of Italian Renaissance art, but Rome isn’t far behind! Thanks to the lavish commissions ordered by a series of fabulously wealthy patrons in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Eternal City soon began to exert an irresistible pull for some of the greatest artists the world has ever known. But whilst you’re definitely familiar with the era-defining works of Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel and Raphael in the nearby Raphael Rooms commissioned by the art-obsessed Pope Julius II, there’s a fabulous world of lesser-known Renaissance gems hiding in churches and chapels all across the city waiting to be discovered.

This week on our blog we wanted to showcase 7 of our favourite examples of Renaissance art in Rome that might not be already on your radar. Next time you visit Rome make sure to include these fabulous chapels on your itinerary, and experience first hand the the extraordinary flowering of artistic creativity that made Renaissance Rome one of the wonders of the Western world.

1. Pietro Cavallini, The Last Judgement, Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, c.1293

You’ve almost certainly heard of Giotto, the fabulously inventive 13th-century painter whose extraordinary capacity for depicting human expression and modelling three-dimensional space is widely heralded with ushering in the brave new world of the Italian Renaissance. But have you heard of Pietro Cavallini?

Born in Rome in the 1250s, Cavallini’s bold naturalism and classicising style was every bit as important for the evolution of early Renaissance art. Beyond the incredible mosaics that Cavallini produced for the Papal basilicas of Santa Maria in Trastevere and San Giovanni in Laterano, the under-appreciated master also created a stunning Last Judgement fresco in the church of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere that could well be the greatest hidden gem of Roman art.

Painted in around 1293 at the behest of the French Cardinal Jean Cholet (who also commissioned Arnolfo di Cambio to carve the stunning baldacchino above the church’s high altar), Cavallini’s fresco was sadly partly destroyed during an ill-advised 16th-century remodelling of the church. But fortunately the most important part of the work survived - the figure of Christ himself in a mandala carried aloft by a troupe of angels with fabulously colourful wings, flanked by the 12 apostles.

The figures of the apostles are seated on deeply recessed thrones, and each is rendered with a volumetric depth that is startling when compared with the flat, iconic forms typical of Cavallini’s contemporaries. These are real, flesh and blood people occupying real, measurable space - a world away from the glitteringly abstract world of the Byzantine tradition that was still in vogue even as Cavallini began his work. The three-dimensional faces of the apostles and their subtle expressions vividly transport us back to the Eternal City in the closing years of the 13th century, and the first stirrings of the Renaissance.

2. Masolino da Panicale, The Branda Chapel, San Clemente, c1427

In 1425, the 39 year old Masolino da Panicale and the hotshot young Masaccio, 18 years his junior, began work on what would become one of the great masterpieces of Renaissance art: the Brancacci chapel in the Florentine church of Santa Maria del Carmine.

Whilst the reputation of Masaccio was soon ensured for all posterity, Masolino has often been overshadowed by his more illustrious colleague in that great quattrocento double-act. And understandably so: before his tragically untimely death at the age of just 26 in mysterious circumstances in Rome, Masaccio's amazing skill in the art of foreshortening and bold plastic modelling had altered the course of Renaissance art. But Masolino was no slouch, and his sharp eye for narrative detail and virtuoso use of colour make his paintings true treasures of quattrocento craft. You can see his lyrical style at its best in the Roman basilica of San Clemente.

The Chapel of Saint Catherine of Alexandria was commissioned by Cardinal Branda Castiglione. A noted humanist and diplomat, Castiglione was a close friend of Pope Martin V, whose papacy marked the end of the Western Schism and ushered in the beginning of the Roman Renaissance. Castiglione was a long-time patron of Masolino, who decorated the Cardinal’s sumptuous palace in Castiglione Olona as well as accompanying the Cardinal on diplomatic missions to Hungary.

Proud of both his piety and learning, the cardinal's choice of subject matter for his family chapel reflected his commitment to pedagogy - the chapel features scenes from the lives of Saint Catherine of Alexandria of the left wall and Saint Ambrose on the right, both of whom were renowned for their wisdom. One fascinating scene from the life of Caterina sees her take on a troupe of pagan philosophers, who soon convert to Christianity in the face of her undeniably superior intellect. The philosophers are burned alive for their troubles and Caterina is tortured on the wheel for her insolence.

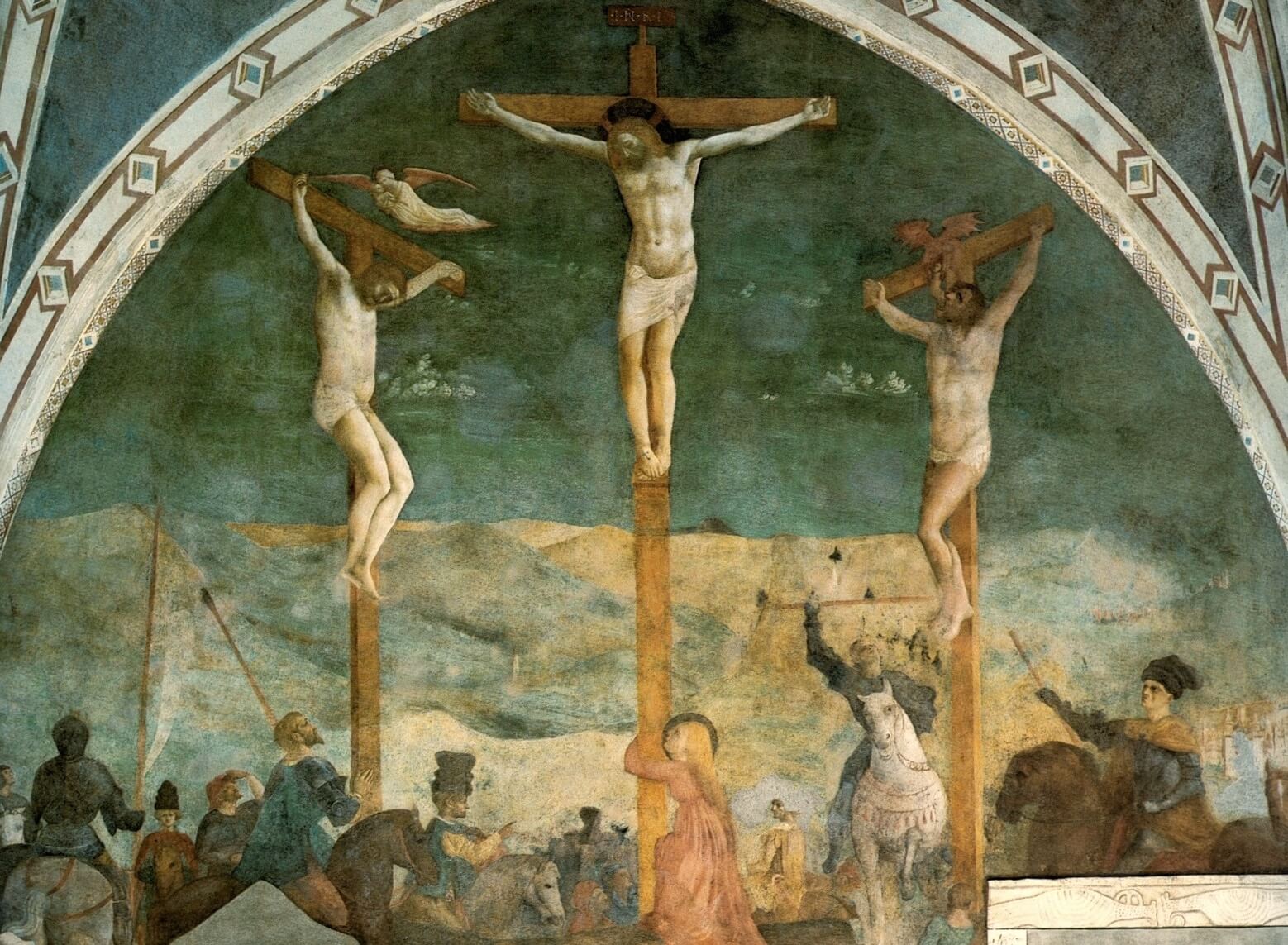

Dominating the back wall of the chapel meanwhile is a wonderful depiction of the Crucifixion, full of cinematic narrative details. Look out for the knights on horseback (evidence, according to some, that Masaccio had a hand in the decorations before his untimely demise) and the detailed portraits of the onlookers, obviously inspired by Masolino’s contemporaries. Look out too for the beautiful depiction of the Annunciation over the chapel’s entrance.

Whilst it’s certainly possible that Masaccio assisted his old collaborator, the Branda chapel is without question Masolino's baby. His frescoes here demonstrate that he was a superbly talented master all his own, and in San Clemente he emerged from Masaccio's shadow to take his place as one of the great artists of the early Renaissance.

3. Fra Angelico, The Niccoline Chapel, Vatican Palace, 1447-52

Located just a stone’s throw away from the iconic Sistine Chapel in the Vatican Palaces, the stunning frescoes of the Niccoline Chapel are probably Rome’s finest 15th-century artworks. Amazingly, most visitors to the city have never even heard of Fra Angelico’s Roman masterpieces, let alone seen them. Unfortunately the chapel is not generally open to the public, meaning the frescoes remain the preserve of specialists and the privileged few. But what treasures they conceal!

Commissioned by Pope Nicholas V in the late 1440s, the glittering scenes depicting the lives and martyrdoms of the early Christian saints Stephen and Lawrence were the work of Florentine master Fra Angelico. Already renowned as one of the finest artists of his generation thanks to his epic work in his native city’s San Marco, the painter-friar was well into his 50s when he was called to Rome to work in the Vatican. Nicholas was a firmly committed patron of the arts, and under his pontificate many of Italy’s finest painters descended on Rome to glorify the papal capital as a new centre of culture and learning.

The new private chapel Nicholas had built for himself was the culmination of his attempts to shift the centre of the Papacy from the Lateran to the Vatican. The frescoes offer a stunning wealth of narrative and pictorial detail, bringing the world of the ancient saints to life with startling vividness. Each scene unfolds in fabulously rendered architectural settings that are like miniature stage sets, displaying an eye for classicising detail fully in line with the Pope’s vision of revitalising Rome in imitation of its ancient splendour.

Here is Stephen debating with the Sanhedrin; there St. Lawrence gives away the riches of the church to the poor and needy. The lives of the two saints culminate in their violent ends: St Stephen is brutally stoned to death outside the city walls of Jerusalem, whilst St. Lawrence is burned alive on a fiery gridiron beneath a row of classical statues. Fra Angelico was assisted in the chapel by his no less illustrious Florentine contemporary, the criminally under appreciated Benozzo Gozzoli (author of the famous decorations in that city’s Palazzo Medici).

4. Antoniazzo Romano and Melozzo da Forli, The Bessarion Chapel, Santi XII Apostoli, 1464

Concealed behind the walls of the church of Santi XII Apostoli is one of the Rome’s great unexpected treats, a sensationally vivid Renaissance world of spectacular portraits, charming landscapes and improbable legends. The fantastic frescoes that light up the secret walls of the Bessarion Chapel are the fruit of a collaboration between Antoniazzo Romano and Melozzo da Forli, commissioned by Cardinal Basilios Bessarion to decorate his funerary chapel in 1464. Despite being widely praised when they were first unveiled in the 15th century, the frescoes of Bessarion’s funeral chapel were forgotten about when the chapel was walled up in the 1700s to create a new chapel for the powerful Odescalchi family in the 1700s. Amazingly, they lay undisturbed until their rediscovery in 1959.

Each of the two main frescoes represents a different apparition of the sword-wielding archangel Michael in the guise of a bull. On the left he appears outside the city walls of Siponto in Puglia, where the shocked locals soon take aim at him with a hail of arrows. The arrows bounce harmlessly off the angel’s hide, and the suitably impressed townsfolk soon realise Michael’s identity. All’s well that ends well as they build a sanctuary in his honour.

To the right Michael materialises again in his bovine form on a windswept island off the coast of Normandy. The fresco refers to a dream of saint Aubert, an 8th-century French bishop of Aranches who was directed to build a sanctuary to Michael at the site where he saw the beastly apparition. Amongst the brilliantly painted figures to Aubert’s left are two fascinating contemporary portraits: the hawkish looking man in red cap and robes is the future Pope Sixtus IV, builder of the Sistine Chapel in the 1480s; to his right, the partially destroyed figure in mauve is the future Julius II, the infamous ‘warrior pope’ who years later would commission Michelangelo to paint his masterpiece on the Sistine ceiling.

The variety of the different types of monks and priests portrayed here in harmonic procession, from Greek Basilian monks in black representing Eastern Christianity to Franciscan friars in brown robes hymning psalms, recalls the cardinal’s ambitious pet project of reconciling the Latin and Greek Orthodox churches. The fabulous colours, beautifully lifelike portraits and dynamic poses of the protagonists make the Bessarion chapel a hidden gem you just can’t miss!

For a detailed guide to this hidden masterpiece of Renaissance art, check out our full guide to the Bessarion Chapel.

5. Pinturicchio, The Bufalini Chapel, Santa Maria in Aracoeli, c.1486

Arriving in Rome with the crack squadron of Tuscan and Umbrian painters that descended on the Eternal City to decorate the walls of the Sistine Chapel in the early 1480s, Bernardino di Betto - known to posterity as Pinturicchio - remained in Rome and quickly became the city’s most sought-after artist. In addition to the fabulous frescoes he created for the Borgia Apartments in the Vatican (click here for a guide to the Borgia apartments), the Bufalini Chapel in Santa Maria in Aracoeli might just be his finest masterpiece.

The fresco cycle depicts scenes from the life of Franciscan preacher and saint Bernardino of Siena, and were commissioned by consistorial lawyer Niccolò dei Bufalini in the 1480s. Niccoló wished to pay tribute to Bernardino for helping quell the brutal feud between the Bufalini and Baglioni clans in his native Città di Castello a generation earlier.

Every inch of the chapel is covered in extraordinarily rich decorations. Beneath the segmented vault featuring the four evangelists, on the altar wall we see the somewhat decrepit saint in glory being crowned by two angels, flanked by St. Louis of Tolouse and Saint Francis. Christ presides over events from above in a heavenly mandala, whilst a fabulous rocky landscape on the left showcases Pinturicchio’s unique eye for detail. The right hand wall meanwhile sees a group of five men peering illusionistically outwards into the chapel, one of whom has been convincingly identified as the Franciscan prior of the monastery at the time the works were painted.

On the chapel’s left wall the vibrant scene of the funeral of Saint Bernardino unfolds, and here the artist gives full rein to his expressive faculties. Unfolding in the open piazza of an ideal city, the defunct saint lies on a bier as he is surrounded by a throng of onlookers. Look closely at their endlessly varied faces and you’ll gain a vivid insight into Renaissance society - aristocrats dressed in luxurious fabrics (almost certainly genuine portraits of the Bufalini family), beautiful young women and playful children; severe looking functionaries and pious monks; a beggar pointing to his eyes, whose blindness has been miraculously healed by the intercession of the saint. And even perhaps, a portrait of the artist himself, gazing out at us from the extreme right wearing a natty red cap.

6. Filippino Lippi, Carafa Chapel, Santa Maria Sopra Minerva, 1488

In Santa Maria Sopra Minerva’s Carafa Chapel, the young Filippino Lippi showed the city’s elites exactly why he was already considered one of the brightest young things on Florence’s art scene even before he had celebrated his 30th birthday. The fabulously gifted son of Filippo Lippi, himself one of Florence’s most famous painters, Filippino was sent for by the powerful Dominican cardinal Oliviero Carafa in 1488 to decorate his funerary chapel in the Order’s Roman headquarters on the recommendation of Lorenzo de Medici.

Oliviero had cemented his as status as one of Rome’s most important figures as ruthless commander of the Papal fleets. But whilst Carafa’s dream of becoming pope was destined never to be realised, the magnificent chapel would ensure his fame for centuries to come. The Carafa Chapel is dedicated to the Virgin Mary and St. Thomas Aquinas, the rigorously upright medieval theologian and doctor of the church who was the patron saint of the Dominicans.

On the main altar wall Lippi depicted two central scenes from the life of the Virgin, the Annunciation and the Assumption. As the winged angel delivers his message in the Annunciation to Lippi’s strikingly beautiful Mary on bended knee, the Holy Spirit swoops into the scene on a magically painted gust of wind. Somewhat presumptuously, the event takes place not in the surroundings of an ancient Nazarene dwelling, but instead in the book-lined study of Cardinal Carafa himself. Carafa makes an appearance in the scene, kneeling reverently at the Virgin’s feet as Thomas Aquinas makes the introductions.

Mary ascends to heaven in the Assumption above, treading over the clouds with a feather-light step as she ascends towards the chapel’s ceiling and out of our terrestrial vision. All around her animated angels swoop, float and dive, playing musical instruments to herald the mother of God’s journey into the skies to join her son. The whole ensemble marks a vitally important landmark in the evolution of technique in Italian Renaissance art: Lippi successfully adopted a complex perspectival trick known as sotto in su, or ‘from below,’ which enabled figures painted high up on walls to illusionistically appear as if they were looming right above the viewer, dissolving the wall and opening up a view into the heavens.

For more on Lippi’s stunning frescoes, read our in-depth guide to the Carafa chapel.

7. Baldassare Peruzzi, Ponzetti Chapel, Santa Maria della Pace, 1514

You might be familiar with the work of Baldassare Peruzzi as an architect: as designer of Agostino Chigi's luxurious riverside retreat at the Villa Farnesina, Peruzzi ushered in a new era of luxurious suburban villas that combined the comforts countryside living with city convenience. And whilst Raphael's frescoes in the Villa Farnesina take all the plaudits, Peruzzi himself contributed a spectacular painted horoscope for Chigi's edification.

The two great artists were to meet again in the church of Santa Maria della Pace, where Raphael was engaged in frescoing a chapel for Chigi with his famous Sibyls in 1514. Across the aisle of the church, Peruzzi was at the same time employed by Cardinal Ferrando Ponzetti to decorate his family’s chapel. And here too Peruzzi’s work loses nothing in comparison to the nearby work of the ‘Prince of Painters.’

The beautiful altarpiece depicts the Virgin Mary flanked by St. Bridget and St. Catherine (who leans on her by now familiar wheel) - the figures are solidly rendered in three-dimensions and amply demonstrate the High Renaissance preference for highly sculptural modelling. Even more impressive is the portrait of the donor Cardinal Ponzetti himself, who kneels humbly at Bridget’s feet.

Above, Peruzzi divided the hemispherical dome into three levels of frescoes depicting scenes from the Old and New Testaments, surrounded by marvellously colourful fictive mosaics. These sparkling miniatures tell stories like the Creation of Adam and Eve, Judith Beheading Holofernes, the Sacrifice of Isaac, the Rest on the Flight into Egypt, Noah’s Ark and many more. Each scene offers a fascinating window into the religious and aesthetic world of Rome in the High Renaissance.

We hope you enjoyed our guide to some of Rome’s most spectacular but little-known gems of Renaissance art! To continue your journey into the magnificent world of Renaissance Rome, be sure to check out our Travel Destinations episode, where Through Eternity founder Rob Allyn is off in search of the masterpieces of this Golden age of art and culture.