The Uffizi gallery is without question the world's greatest collection of Renaissance art.

Housed in a magnificent 16th-century palace built by the powerful Medici family, the Uffizi became the modern world’s first public museum when Cosimo de’ Medici made the family’s art collection accessible to the public in 1574, and has for centuries attracted art lovers from around the globe.

Boasting an unrivalled array of masterpieces from the brushes of Italy’s finest painters, a visit to the Uffizi is a must on any tour of Florence.

In part one of our two part guide to the Uffizi Gallery, we’re taking a look at masterpieces of the collection from antiquity, the late middle ages and the first half of the Renaissance.

Florence Tours

Visit the Uffizi Gallery

You probably associate the Uffizi gallery mostly with masterpieces of Renaissance art, but there are a few ancient treasures woven into the mix at Florence’s premier art gallery. One of the finest classical works on display is this depiction of Cupid and Psyche.

The story goes that the love goddess Venus, jealous of the preternatural beauty of the mortal Psyche, ordered her son Cupid to take vengeance on her by making her fall in love with the ugliest creature she comes across.

Cupid is soon overcome by Psyche’s charms himself, however, and fails at his task; he pricks himself with one of his own arrows, instantly falling hopelessly in love with Psyche. After many vicissitudes and plenty of shocking behaviour on the part of Venus, the star-crossed lovers are finally accepted into the godly company on Mount Olympus, with Psyche becoming the goddess of the soul.

Discovered in 1666 on the Caelian hill in Rome, the marvellous sculpture portraying the lovers in the Uffizi was restored by Giacomo Antonio Fancelli before being snapped up by Cosimo III de Medici and carted off to Florence, where it was soon installed in the Uffizi. Look out for Psyche’s butterfly wings – in Greek, psyche means ‘butterfly’ as well as ‘soul,’ explaining this common iconography.

“In painting Cimabue thought he held the field, and now it’s Giotto they acclaim – the former only keeps a shadowed fame.” So wrote the great Italian poet Dante in his Divine Comedy, heralding the extraordinary rise of the painter Giotto in the early years of the 14th century.

Dante was right – no story of art can be written without reckoning with the enormous influence and long shadow of his illustrious contemporary, responsible for ushering in a new understanding of the boundaries of pictorial expression and paving the way for the incredible artistic flowering of the Italian Renaissance.

In Florence’s Uffizi Gallery we come face to face with the revolution Giotto helped bring about in the artist’s Ognissanti Madonna, painted for the church of that name when Giotto was nearing the height of his fame in the opening years of the 14th century.

The tempera panel features Mary holding her infant son in her arms, enthroned in a Gothic tabernacle surrounded by angels. With its gold background and static composition, the painting apparently still has one foot in the Middle Ages. Yet in its technique and artistry it is embarking on an entirely new endeavour: Giotto’s figures have substance, exist in three dimensions and seem to feel like living, breathing human beings.

Gentile da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi is a sumptuous visual treat, and a glittering example of the highly decorative International Gothic style of painting that held sway in Florence in the early years of the 15th century.

The painting follows the procession of the Magi as they follow the light of a star towards the site of Christ’s birth in the foreground, where they prostrate themselves at his tiny feet.

The work was commissioned by Florence’s richest citizen, the banker Palla Strozzi, for the church of Santa Trinità, and features portraits of both Palla and his father Onofrio amidst the cast of characters populating the panel.

The luxurious fabrics worn by the three kings, the exotic plants and animals springing up here and there across the scene, the sparkling golden details, the fabulous gilded frame – all this and more demonstrates the patron’s fabulous wealth, and makes the Adoration of the Magi Gentile’s finest and most representative work.

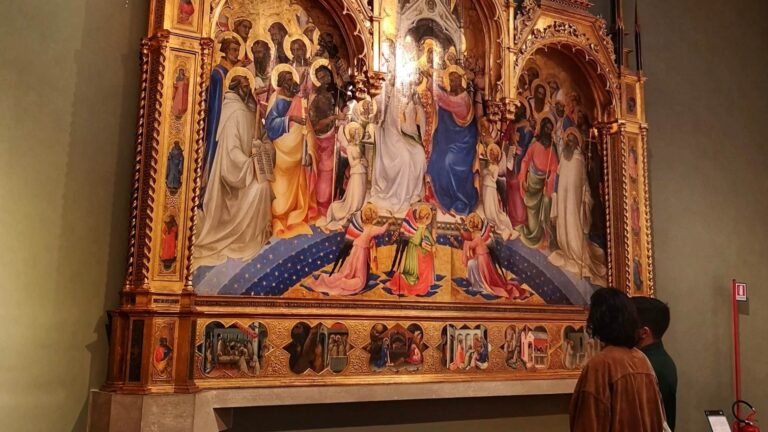

Another masterpiece of the International Gothic style of painting that predominated in Italy during the 14th and early-15th centuries, Lorenzo Monaco’s Coronation of the Virgin offers a spectacular companion piece to Gentile da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi in the Uffizi gallery.

This large polyptych altarpiece portrays Christ crowning his mother Mary as the Queen of Heaven as rows of saints and angels look on above a rainbow of stars – an abstracted, symbolic depiction of the universe’s celestial spheres common in medieval painting.

As his name implies, Lorenzo Monaco was himself a monk, and he painted this masterpiece in 1414 for the high altar of the Santa Maria degli Angeli abbey in Florence where he lived.

The sensational gilded and pinnacled frame is original, and thanks to its distinctive shape forms an intrinsic part of the work – a magnificent example of the intricate and varied craftsmanship that went into every aspect of the creation of an early-modern altarpiece.

Even though he was painting around the same time as Gentile da Fabriano and Lorenzo Monaco, the innovative art of Masaccio takes us into a new stage of the Renaissance.

Gone are the whimsical narrative details and miniaturist’s focus on the sumptuousness of fabrics, while the role of gold leaf has been reduced to the holy figures’ haloes. Instead, in the painting known as Saint Anne Metterza, we are confronted with a far more minimalist composition, one in which properties of space and light take centre stage.

The panel is rigorously arranged according to the new principles of perspective as recently outlined by Filippo Brunelleschi: the three principal figures, St. Anne, her daughter Mary and the infant Christ are convincingly arranged in a 3-dimensional space as angels (painted by Masaccio’s collaborator Masolino) hold up a cloth around the holy group.

The altarpiece was commissioned by the Buonamici family, who were particularly devoted to the figure of Saint Anne, for the church of Sant’Ambrogio in Florence.

Armour clangs and horses scream in Paolo Uccello’s daring depiction of the Battle of San Romano. The panel is one of three paintings commissioned by Florentine bigwig Lionardo Bartolini Salimbeni to celebrate the city-state’s famous victory over the troops of neighbouring Siena in 1432, and in it Uccello captures the chaos of war like few artists had before or since.

Armed knights ready their lances, their steeds buck and rear, and the ground is littered with broken weapons and bodies. At the centre of the action, the soldier-for-hire Niccolò da Tolentino fells his opposing general Bernardino della Carda with a lance, signalling emerging Florentine ascendency.

Uccello was highly admired by his contemporaries for the frenetic energy he instilled into his figures, as well as his ability to show horses from so many different angles in this whirlwind of flesh and metal. His virtuoso skills in perspective, evidenced in the dramatically foreshortened bodies and the complex patterns traced by broken lances and weaponry, were founded on highly advanced mathematical study which helped usher in a new, more scientific approach to pictorial composition in Western art.

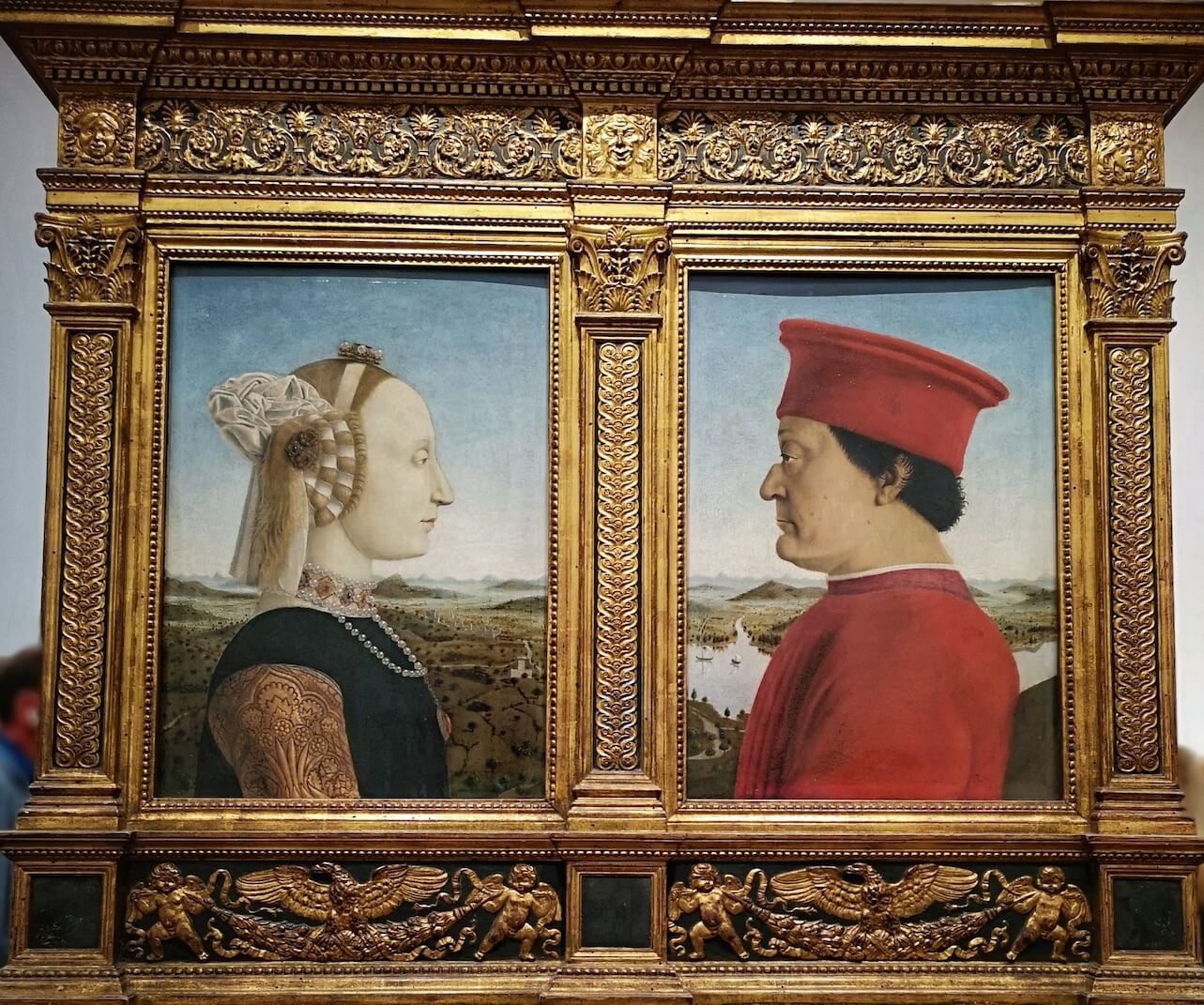

One of the most highly lauded portraits of the Renaissance, Piero della Francesca’s depiction of the powerful Duke of Urbino and his wife offers a probing psychological insight into the minds of its sitters.

Federico was something of a paradoxical figure: a fearsome warrior and mercenary soldier, his impassive gaze and misshapen nose reflect that this was not a man to be messed with. And yet, the Duke was also one of the Renaissance’s most cultured figures, transforming Urbino into a haven of learning and a magnet for renowned artists, writers and architects during his reign – so it was for the famous Piero della Francesca, who was a frequent guest at the Urbino court.

On the rear of the panel, the Duke and Duchess are represented being carried triumphantly on ancient wagons in a nod to Federico’s classical learning, accompanied by personifications of Christian virtues.

Take a closer look at Battista Sforza: her ivory-pale skin is in stark contrast to the hearty vigour of her husband’s complexion. This is not by chance, or merely a reflection of contemporary fashion for a ‘bloodless’ look.

The duchess had in fact died in 1472, a year before Piero della Francesca began work on the portrait. The painting thus doubles as a courtly portrait and tender memorial to a deceased companion.

To continue your exploration of the Uffizi Gallery, check out part two of our guide here!

Book Your Uffizi Experience