It's a safe bet that you most closely associate the life and work of Picasso with Paris, and indeed it was in the French capital that the 20th-century’s greatest artist produced many of his finest triumphs as the pied piper of the European avant-garde. But the young Spanish artist, already on the cusp of greatness as an extraordinarily precocious teenager, spent some of the most formative years of his life in Barcelona, where he moved with his family in 1895. To understand Picasso you need to visit the Catalan capital and the city’s magnificent Picasso Museum in particular, which houses some of the artist’s greatest masterpieces in the beautiful surroundings of a Gothic palace.

From Picasso’s earliest portraits and realist narratives to his Blue Period, development of Cubism and an incredible engagement with Diego Velazquez’s Las Meninas, if you have even a passing interest in Picasso this is one museum you can’t afford to miss! To help you make the most of your time in Barcelona’s Picasso Museum, we’ve put together a list of some of our favourite paintings in the collection.

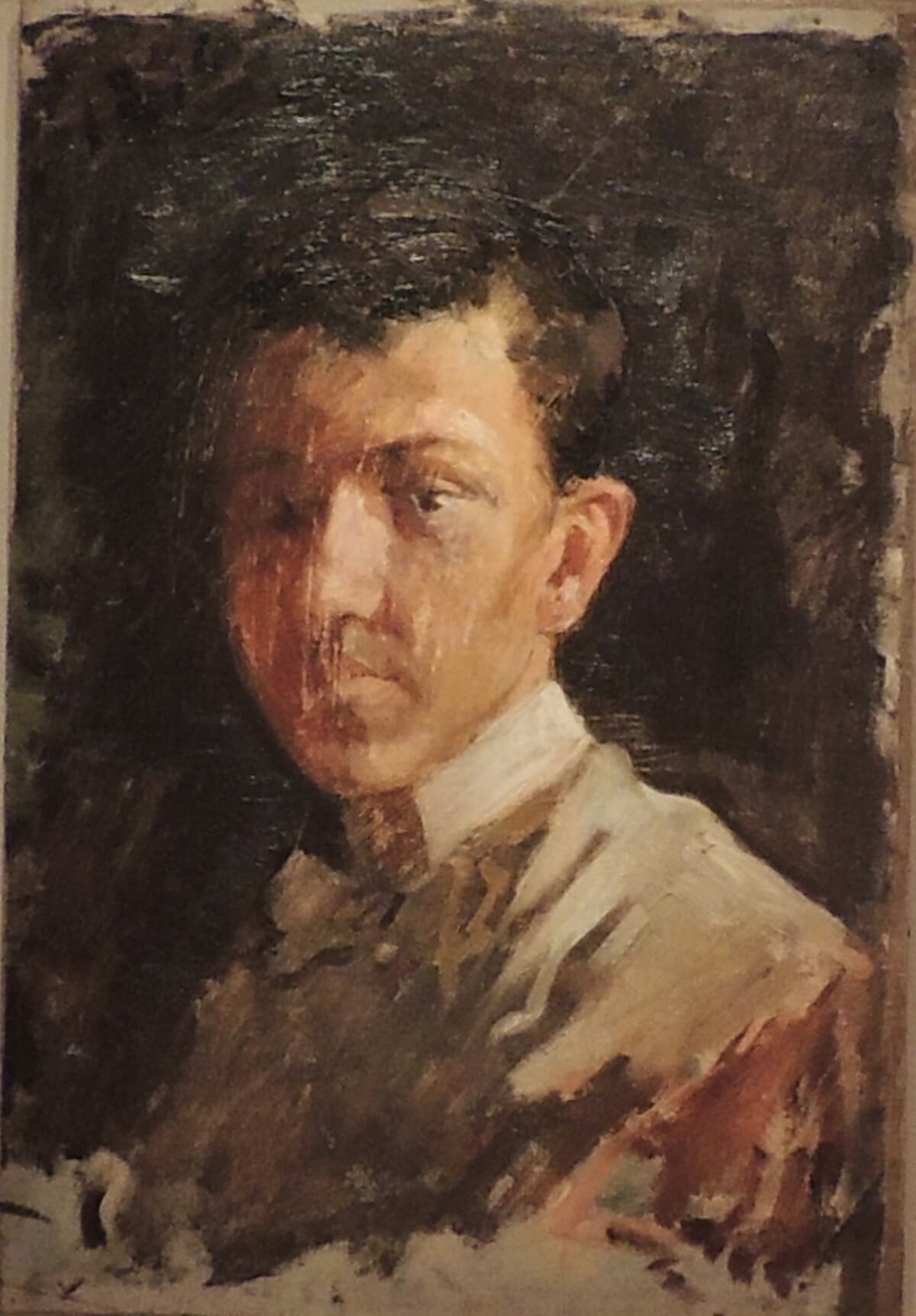

Self Portrait, 1896

The precocious Pablo Ruiz (the artist we know as Picasso would only adopt his mother’s surname a few years later) was just 15 when he painted this brooding self-portrait that already demonstrates his command of technique and eye for human expression, developed and refined first in the art academy in La Coruña - where he and his family lived between 1891 and 1895 - and then at Barcelona’s La Lonja School of Art after their move to the city in that year. Picasso frequently authored self-portraits and sketches of his parents during this period. Although the teenaged Picasso who looks out at us from the frame is, as you would expect, somewhat boyish, his intense stare and flashing eyes give powerful hints of the passion and intellect that would drive him towards a career of astonishing invention and originality in the years to come.

First Communion, 1896

Picasso’s first large-scale narrative oil painting, once again painted when he was just 15, marks the artist’s impressive debut into the public art world. A fine example of the kind of rigorously composed composition that was in vogue in academic circles during the 19th century, the scene unfolds before the altar of a church where a young girl is poised to take her first communion as her parents and an altar boy watches on. The brilliant colours - including the girl’s shining white dress reflecting her innocence, the flashes of red in the altarboy’s vestments and the warm glow of the candles combine to create a sumptuous and tactile visual world. The unmistakable features of Picasso’s own father José Ruiz y Blasco stare down from the face of the girl’s father - the young artist frequently used his obliging parents as models in his earliest works. Picasso here already seems to have more or less perfected the somewhat conservative formal style he was being taught at art school, and was ready for greater things. As the artist himself later observed, ‘It took me 12 years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.’

Science and Charity, 1897

Buoyed by the triumph of the celebrated The First Communion, Picasso’s father decided to rent his son a studio at 4, Carrer de la Plata, where he could dedicate himself more fully to his artistic development. It was here that he painted Science and Charity in the following year, a vivid demonstration of his extraordinarily precocious talent and the high-point of Picasso’s juvenile period. The canvas is a carefully composed composition of social realism shot through with allegory in which a woman feebly lies on her sick bed attended by a doctor and a nun - each representing institutions that the fin-de-siecle bourgeoisie of European cities such as Barcelona deeply admired. The cogent narrative style and highly competent creation of a convincing three-dimensional space demonstrates that the young Pablo Ruiz was fully equipped with the tools necessary to forge a career as a successful, conventional academic painter. It was a path, however, that he was to shortly reject.

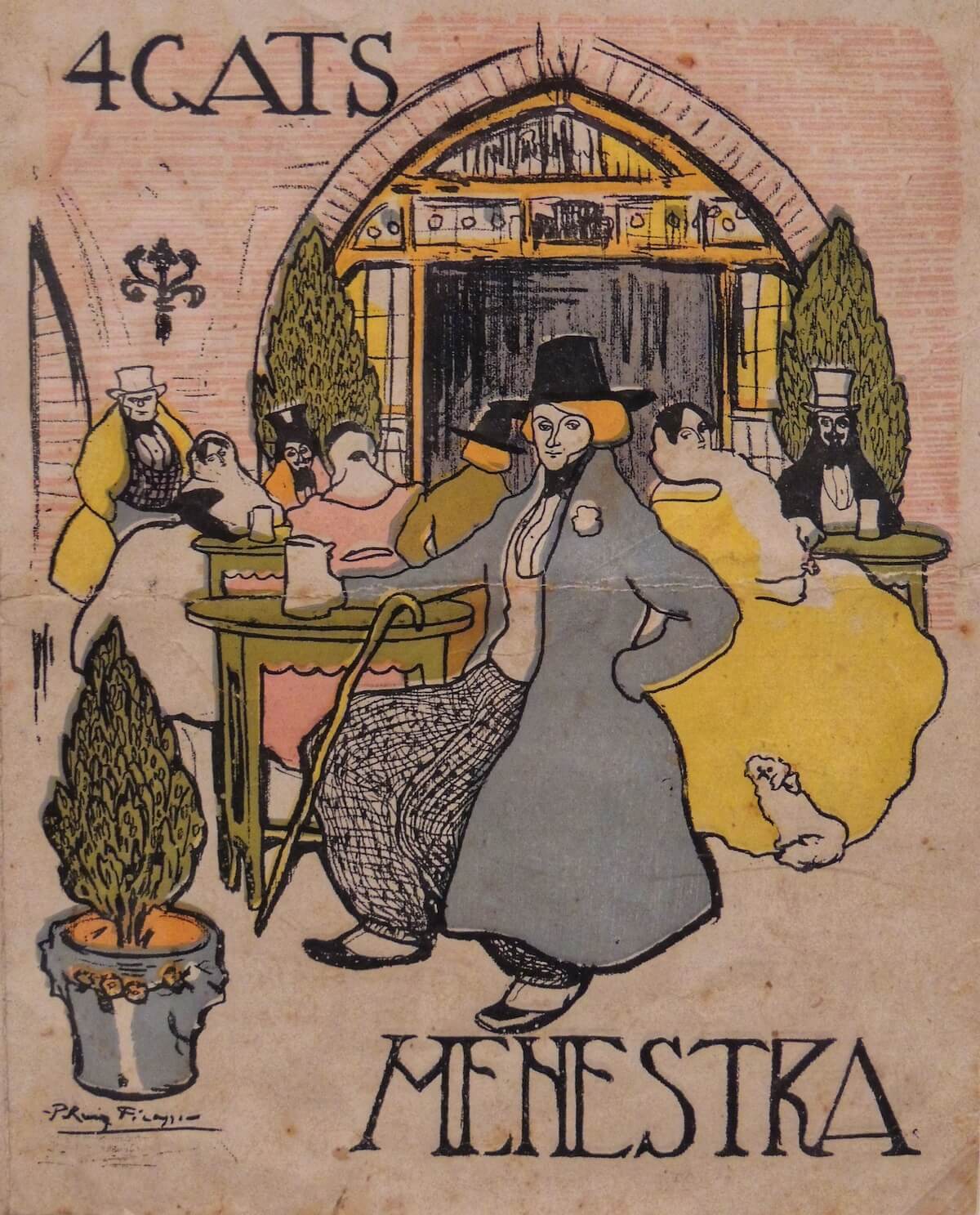

Menu of Els Quatre Gats, 1900

Opened in 1897 and modelled on the iconic Chat Noir cafe in Paris, where the greatest literary and artistic lights of the European avant-garde gathered to chat, drink and exchange ideas, the cafe-bar Els Quatre Gats sought to provide a similar meeting point for Barcelona’s burgeoning modernist movement. Located in a stunning edifice designed by Josep Puig i Cadafalch, Pere Romeu’s Gothic quarter establishment soon became one of Barcelona’s most happening spots, and counted a young Picasso amongst its cast of regulars. Picasso’s vibrant sketches impressed Romeu, who wasted little time in commissioning the teenager to design the bar’s menu: the highly stylised portrayal of fashionable turn-of-the-century Barcelonans lounging at their tables beneath the pointed arches of Els Quatre Gats was an instant modernist design classic.

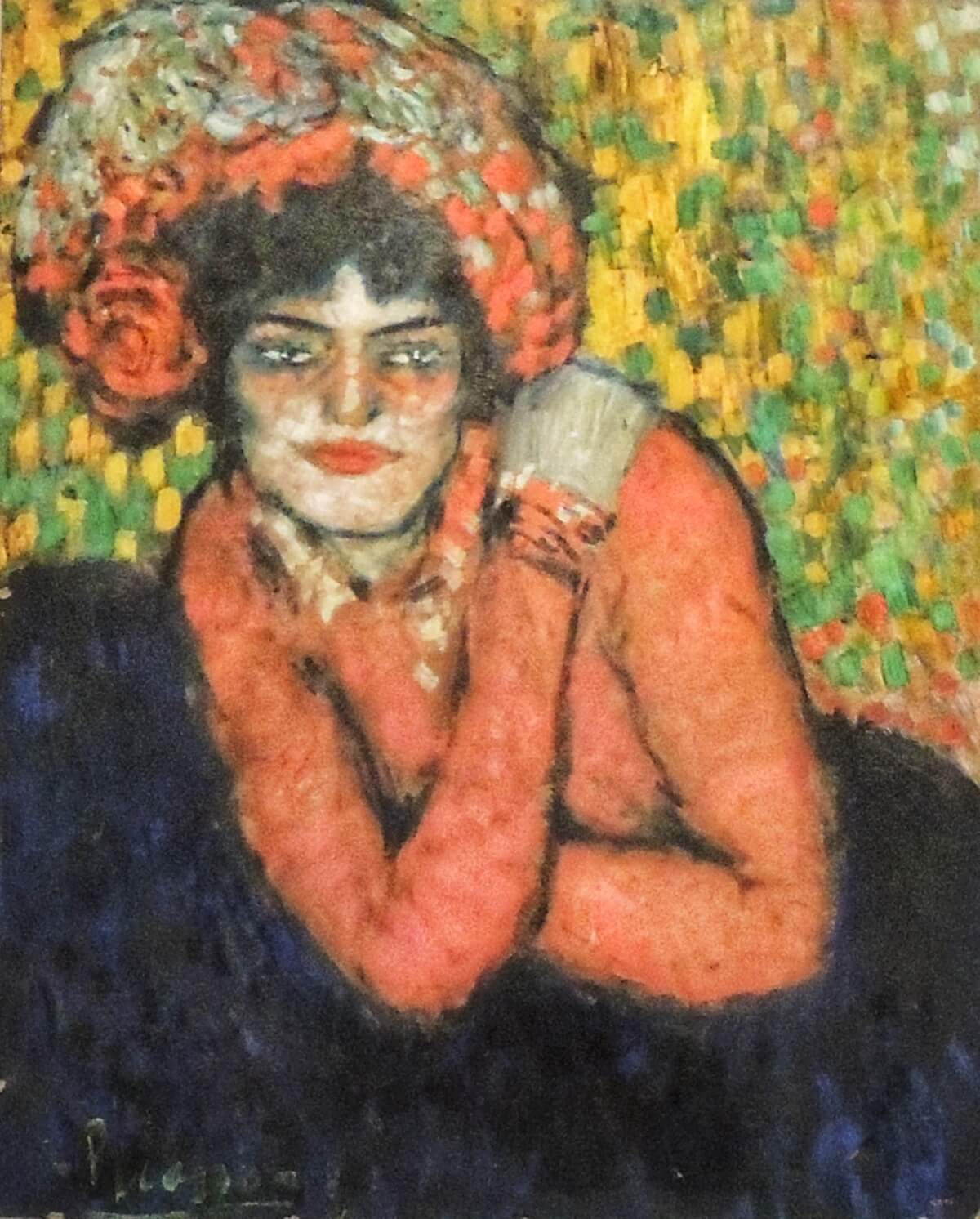

The Wait (Margot), 1901

One of the most visually arresting works in Barcelona’s Picasso Museum, The Wait depicts a young woman in extravagant headdress, face flushed and eyes narrowed in a vacant stare. Variously described as a street-walking prostitute, a morphine addict or both, the woman is typical of the characters peopling Picasso’s work in this period. Picasso was a tireless observer of all aspects of modern life after his move to Paris, and many of his works from this period are un-idealised street scenes depicting the denizens of the City of Light’s seedy underbelly. Margot was one of the most highly regarded works to feature in Picasso’s solo exhibition at the Vollard Gallery in 1901, a highly successful venture that helped launch the young artist on the fast-track to fame. The free, almost frenzied brushstrokes and expressionistic use of vibrant colour draw from the pioneering stylistic developments pioneered by the older post-impressionist artists Seurat, Toulouse-Lautrec and Matisse.

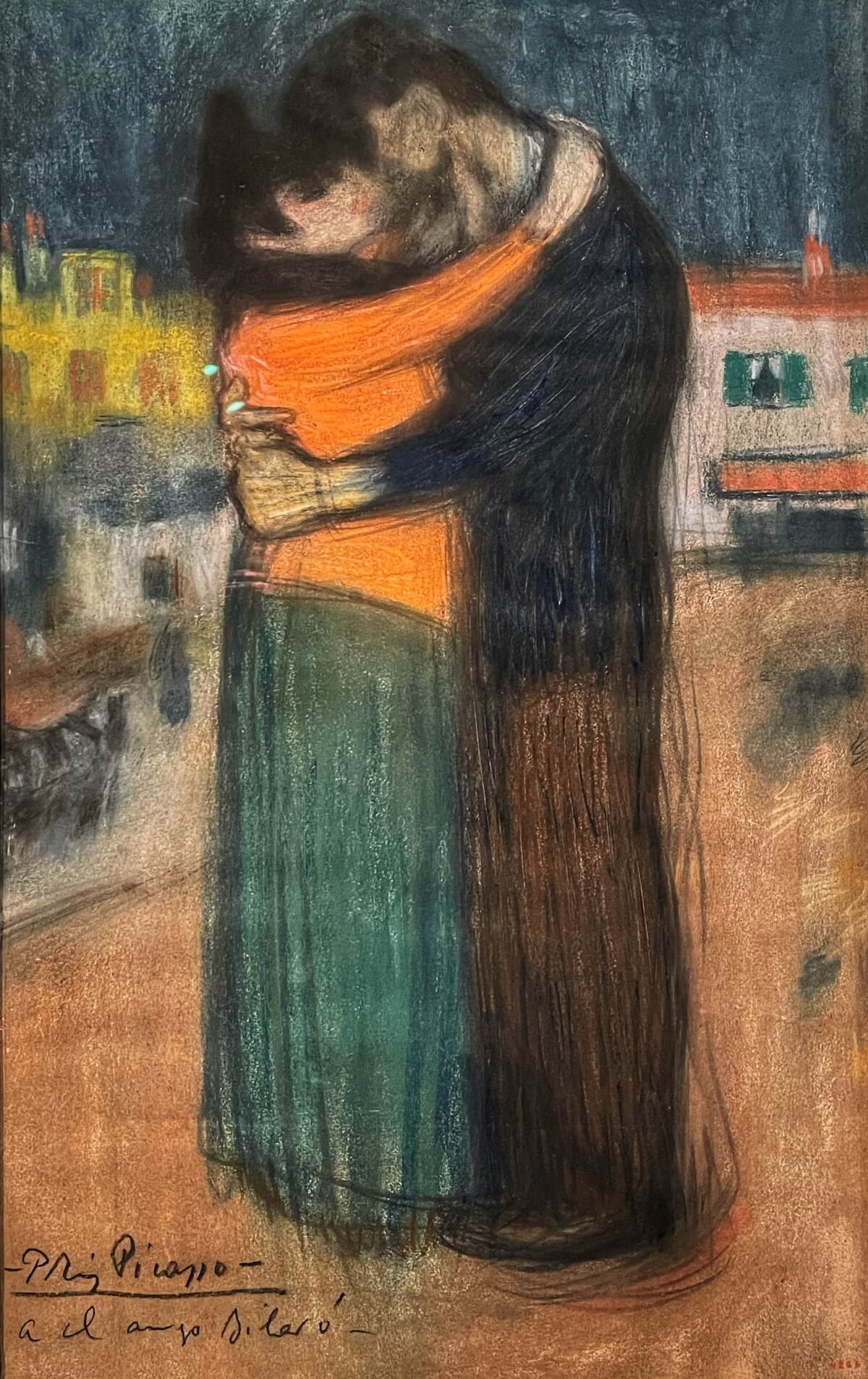

The Embrace, 1900

Another slice of city life as depicted by Picasso on his first Paris sojourn, this simple but profound painting portrays a couple sharing a tender embrace, their affection for one another apparently so deep that they appear to be a single entity, their individual bodies inextricable. Emphasising this sensation of two becoming one, the figures have been deprived of recognisable facial features or physiognomies, emerging instead as inter-linking blocks of colour. Behind the kissing couple, the charming pastel houses and tiled roofs of Montmartre firmly anchors the scene in turn-of-the-century Paris.

The Dead Woman, 1903

Picasso’s so-called Blue Period, in which the artist’s work came to be dominated by a sombre and melancholy palette of depressing blues and sickly greens, began in 1901. Although still only 19, Picasso had by this time settled comfortably into the Barcelona avant-garde, where his closest companion was the poet Carles Casagemas. That year, however, Cassagemas tragically shot himself at a party in Paris, and the death of his friend immediately had a profound effect on Picasso’s work. ‘It was thinking about Casagemas that got me started painting in blue,’ the artist would later write. Scenes of grief, deprivation and social isolation predominate in Picasso’s work from this period, and a number of these canvases are housed in the Barcelona Picasso Museum. Perhaps most striking of the lot is this portrait of a recently deceased woman in the morgue of the Hospital de Santa Creu i Sant Pau, painted after Picasso paid a visit to the institution in the company of his friend Doctor Jacint Reventós.

The Passeig de Colom, 1917

This small cityscape vividly demonstrates the rapidly evolving cubist sensibilities of the artist, painted on a visit to Barcelona from Paris in 1917. Serge Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes was in town with their ballet Parade, for which Picasso had designed extraordinary cubist costumes, fantastical sets and staging. The bizarre costumes of a number of the characters recalled fragmented skyscrapers and sweeping boulevards, and Picasso carried over this same modernist sensibility to this depiction of one of Barcelona’s principal thoroughfares, seen from the viewpoint of a balcony of the Ranzini hotel, where Ballet Russes performer (and Picasso’s future wife) Olga Khokhlova was staying. Although the perspective is highly distorted, certain recognisable features ground the scene fundamentally in the Catalan city: the Spanish flag, the statue of Columbus on a column and the glittering waters of the Mediterranean sea in the background.

Portrait of Blanquita Suárez, 1917

Picasso’s investigations into cubism during his 1917 sojourn in Barcelona are again reflected in this portrait of the Catalan singer and variety-show star Blanquita Suárez. Theatres, dance-halls and concert houses were a constant source of inspiration for Picasso throughout his life, and here the dynamic world of show-business is captured in the restless movement of Suárez, essentialised in a series of abstracted geometric shapes. She carries a fan in one hand as she strides forcefully into frame, her skirt swishing around her ankles.

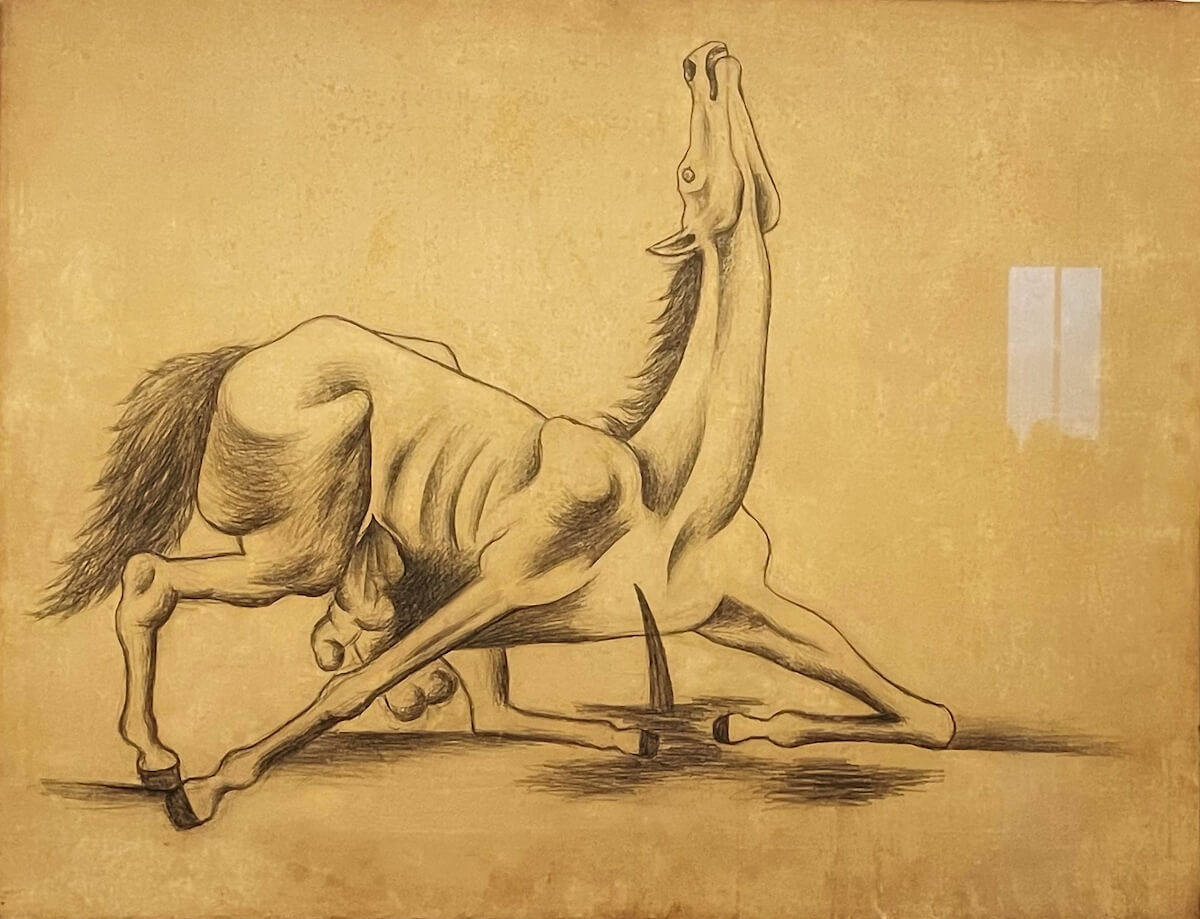

Gored Horse, 1917

Shocking in its violent immediacy, the precise, virtuoso draughtsmanship of Picasso’s charcoal drawing contrasts grotesquely with its violent subject matter: an impaled horse rearing up in agony during its death throes, body horrendously contorted by pain as blood and viscera spill from his stricken belly. Picasso’s long-standing fascination with the bloody world of bullfighting provides the context for the composition; after attending the corrida dedicated to the Virgin of El Pilar on October 12, 1917, the artist produced a series of sketches depicting the brutal drama, culminating in this grisly expressionistic masterpiece where the sepia-tinted canvas recalls the sand of the arena on which the doomed horse breathed its last.

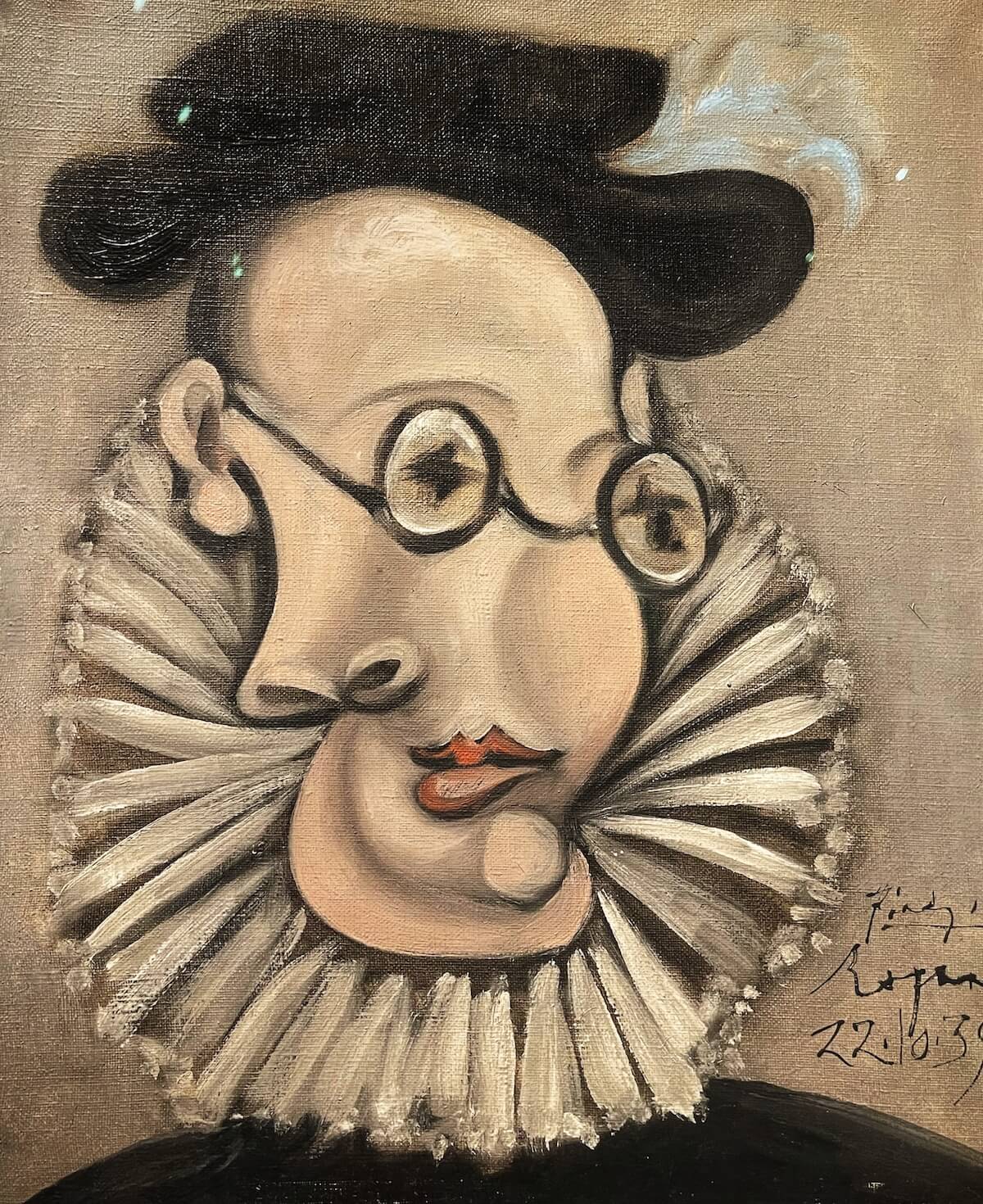

Portrait of Jaume Sabartes with Ruff and Cap, 1939

A longtime close friend and colleague of Picasso, Jaume Sabartes played an instrumental role in the artist’s career from the time the two used to hang out together in the Barcelona cafe and avant-garde fortress Els Quatre Gats. After spending many years in South America, Sabarte returned to Europe in 1935, whereupon he became Picasso’s personal secretary. An avid collector of the master’s works, Sabartes donated much of his collection to the Barcelona City council in 1963, and his donation formed the nucleus of the new Picasso museum. To avoid censorship from the hostile Franco regime of whom Picasso was a staunch critic, the Museum was in fact originally known simply as Sabartés Collection. Picasso painted his first portrait of his friend Sabartes way back in 1899, and he became a regular sitter over the coming decades. Sabartes requested a comical portrait of himself jauntily attired in the manner of a 16th century noble from Picasso in 1938, and the artist obliged with this canvas the following year, in which the sitter’s features are playfully distorted but immediately recognisable.

Portrait of Jacqueline, 1957

Picasso’s third (and final) wife, Jacqueline Roque was born in Paris in 1927. The pair met in 1954 in the pottery studio on the Côte d'Azur where the artist was experimenting with ceramics, and despite the significant age gap (Picasso was 72 when they met, Jacqueline only 27) soon shacked up together in Cannes, where they would spend the majority of the next 20 years together until the artist’s death. Picasso painted, sculpted and drew his wife countless times, and Jacqueline appears regularly in Barcelona’s Picasso Museum - perhaps most memorably in this 1957 portrait, where she is pictured in elegant profile, hair wreathed in a green headdress.

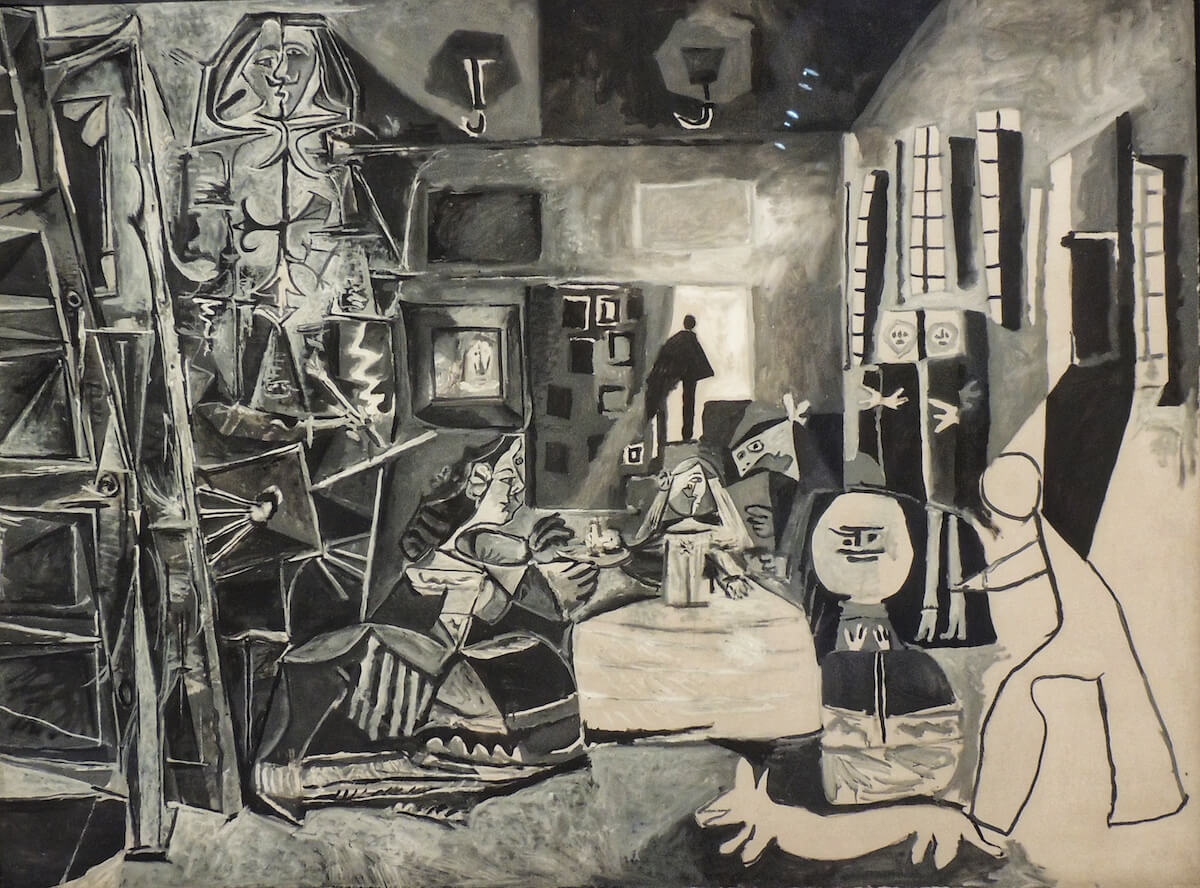

Las Meninas (Group), 1957

Although Picasso is justifiably considered one of the 20th century’s most innovative artists, a painter whose reconceptualisation of represented space expanded the imagined limits of the visual arts, the modernist master was nonetheless a great student of the history of art. So much so that during an intense period of creativity over the course of 5 months in 1957, Picasso set himself the daunting task of revising and re-imagining Velazquez’s iconic 17th-century royal portrait Las Meninas in a way that would simultaneously remain faithful to the original and reflect his own artistic principles. As Picasso himself described the task:

If one were to copy Las Meninas in perfectly good faith, upon reaching a certain point if I were the one copying I would say to myself: ‘what if I just placed this a tiny bit more to the right or left?’ I would try to do it in my own way, forgetting about Velázquez. The challenge would surely make me modify or change the light, due to having changed the position of a figure. In this way, little by little, I would paint a Meninas that would seem detestable to a pure copyist – this Meninas would not be the one he thought he saw on Velázquez’s canvas, but it would be my Meninas.’

The result of the artist’s method was no fewer than 44 separate studies in which Velazquez’s Meninas did indeed slowly metamorphosize into something unmistakably and uniquely the work Picasso. Occupying pride of place in a dedicated gallery, the Meninas studies are arguably the Museum’s magnificent highlight.

Las Meninas (Infanta Margarita María), 1957

The figure to recur most frequently in the Meninas cycle in the Picasso Museum Barcelona is that of the five year old daughter of King Philip IV of Spain, the Infanta Margarita Maria. She is in many ways the star in Velazquez’s original painting, staring maturely out of the frame, clad in a dainty white dress and attended to by a pair of ladies in waiting. Here, despite being given the full-on Picasso treatment - wild coloristic transformations and formal abstractions, distortions of proportions and a flattening of dimensions - the elegant young noble is still instantly recognisable in her sweet features and sumptuous garments. The mimetic force of Velazquez and the sheer expressive power of Picasso seem to harmoniously coexist in this wonderful canvas.

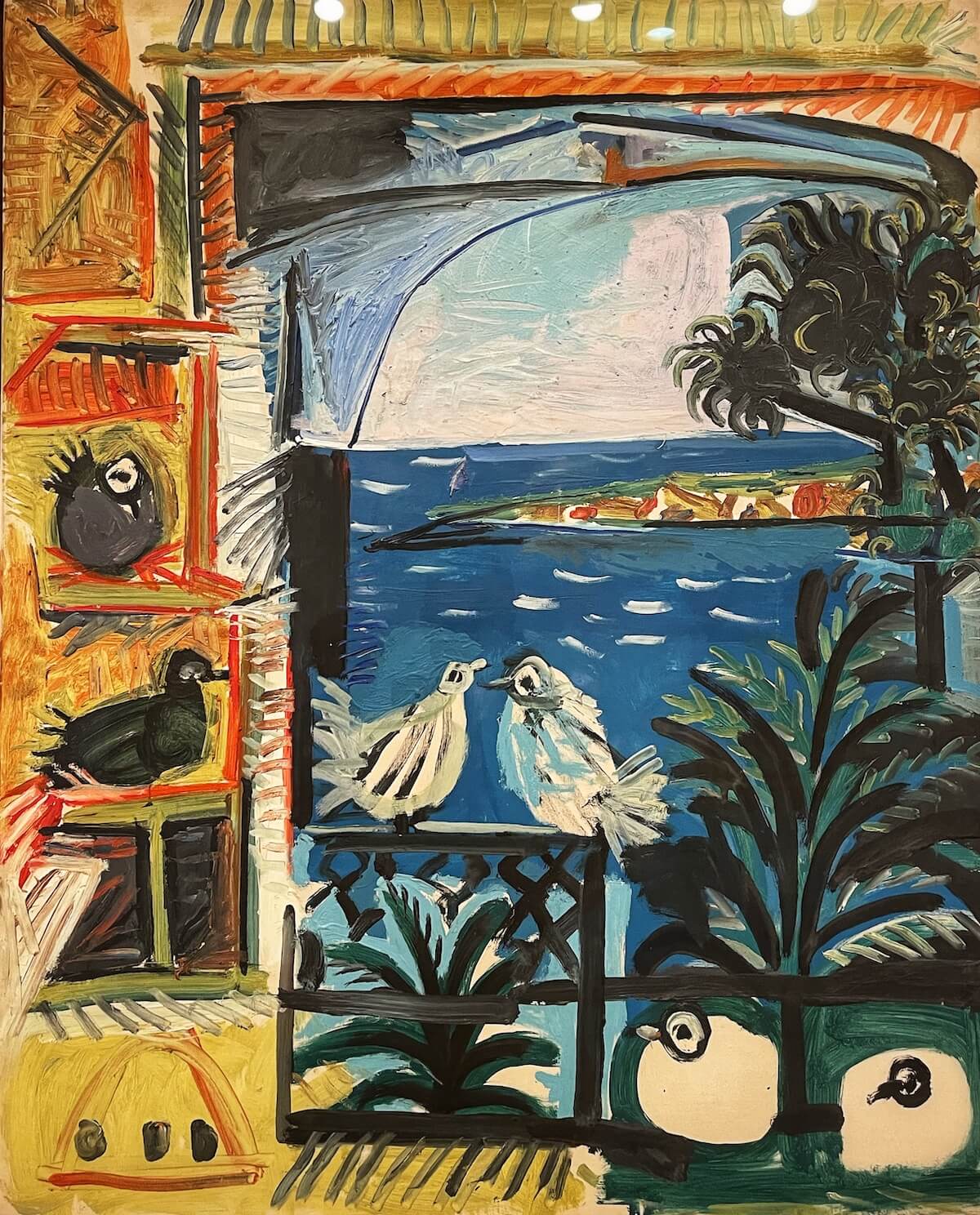

The Pigeons, Cannes, 1957

In the midst of his obsessive re-imagining of Velazquez’s Las Meninas, Picasso decided to engaged in a brief artistic reset: from the 6th to 14th of September 1957, the painter would produce no fewer than nine paintings of the pigeons that perched on the third-floor balcony of his sea-facing studio in Cannes. These vibrant canvases are a riot of colour, land and water bathed in the warm light of a Mediterranean summer, and speak to one of Picasso’s most enduring fascinations: the artist’s father was as pigeon fancier, and some of Pablo’s earliest drawings (also in Barcelona’s Picasso Museum) are detailed studies of the birds. Pigeons and doves recur frequently as a motif in the artist’s work throughout his long career, including the now iconic lithograph that was adopted as a symbol for the Paris Peace Conference in 1949.

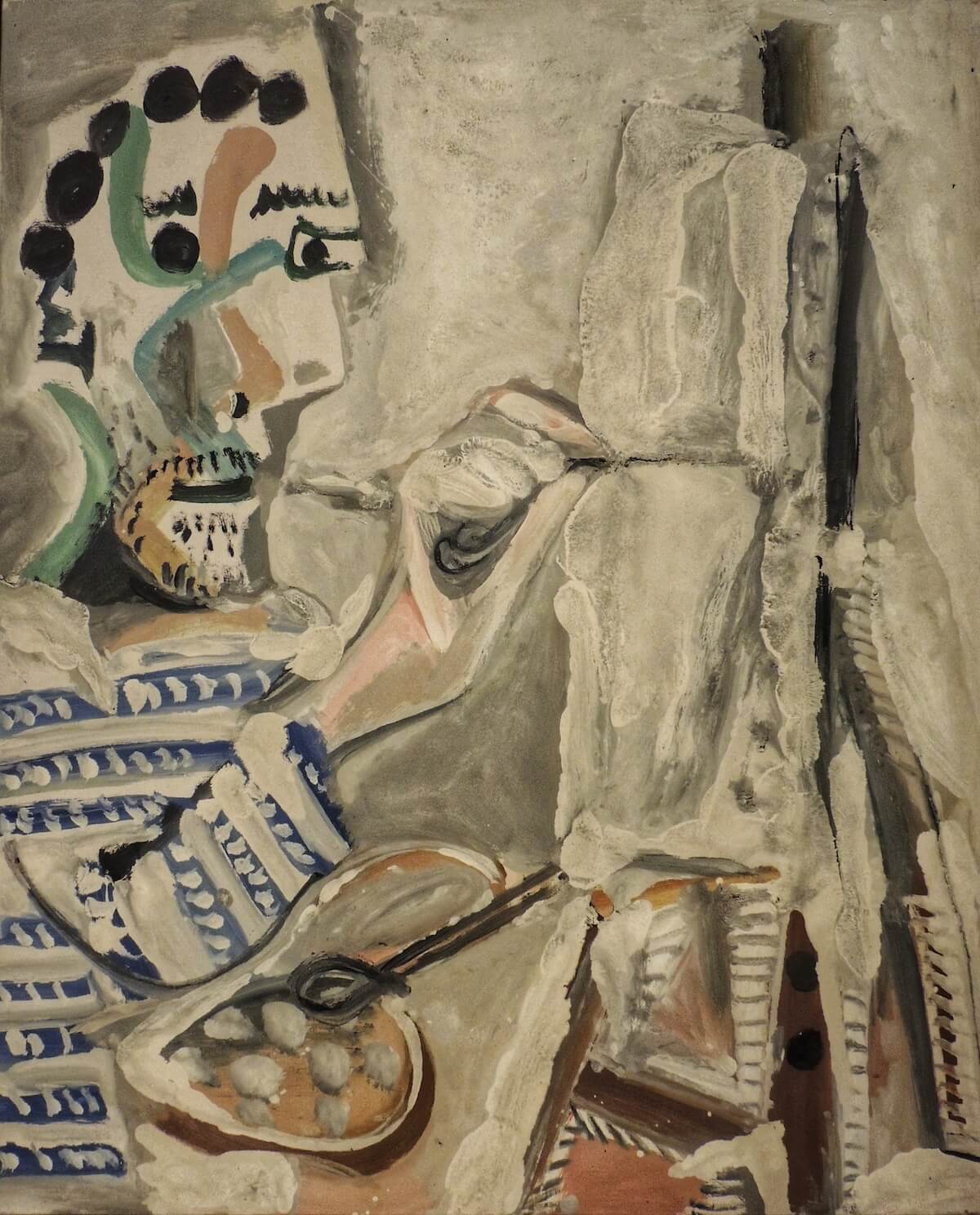

Painter Working, 1965

Picasso had always been fascinated in the act of creation as a physical process, and in this late painting we are treated to an intimate insight into the artist at work. At this late point in his career Picasso had broken free of the rigorous formal concerns that characterised much of his earlier output, replaced with a spontaneous, free-flowing style that seems to celebrate both the freedom of the creative process and the materiality of paint and canvas. Jauntily clad in a signature blue and white striped Breton sailor shirt, the artist holds his easel in one hand as he raises a brush towards the canvas he is working on in the other. For some, there is something childlike about the aged artist apparently abandoning the rigour of his craft, whilst for others the sheer expressionistic joy of the painting’s bold forms and colours convey Picasso’s remarkable ability to reinvent himself as an artist well into his 80s.

Through Eternity Tours offer expert-led guided itineraries in Barcelona. To learn more about how the Catalan city shaped the career of one of the twentieth century’s greatest artists and gain a unique insight into the collection of the Picasso Museum, check out our Picasso in Barcelona Tour: In the Footsteps of the Master.