‘Come let me divert you with an old wives’ tale, one that makes a pretty story.’

– Apuleius, The Tale of Cupid and Psyche from The Golden Ass

The bawdy story of the star-crossed love of Cupid and Psyche was one of the ancient world’s most popular tales. Detailing the ups and downs of the forbidden romance between the divine god of desire and a mortal princess, the yarn comes from Apuleius’ Metamorphoses (popularly known as the Golden Ass), the only Roman novel in Latin to survive in its entirety from antiquity.

Apuleius’ novel received a number of retellings in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and seems to have been on everyone’s lips in the second decade of the 16th century. Macchiavell himself wrote a satirical poem based on the work in 1517, and an Italian language translation that had been circulating for years in manuscript was finally published the following year. But no version, no matter how florid the text or loquacious the language, could match the magisterial envisioning wrought by Raphael and his workshop (including future stars in their own right like Giuliano Romano and Giovanni da Udine) on the walls and ceilings of Agostino Chigi’s opulent riverside palace in that same year.

Best Rome Tours

Explore the Best of Rome

As the 16th century dawned in the Eternal City, there were few characters as grand as Agostino Chigi. Banker, financier and business magnate extraordinaire, Agostino had amassed an eye-watering fortune thanks to his monopoly of the alum mines north of Rome and his rise to the position of Vatican treasurer. Employing over 20,000 people in his vast business empire, he was easily the city’s richest man, and his private life was no less lavish.

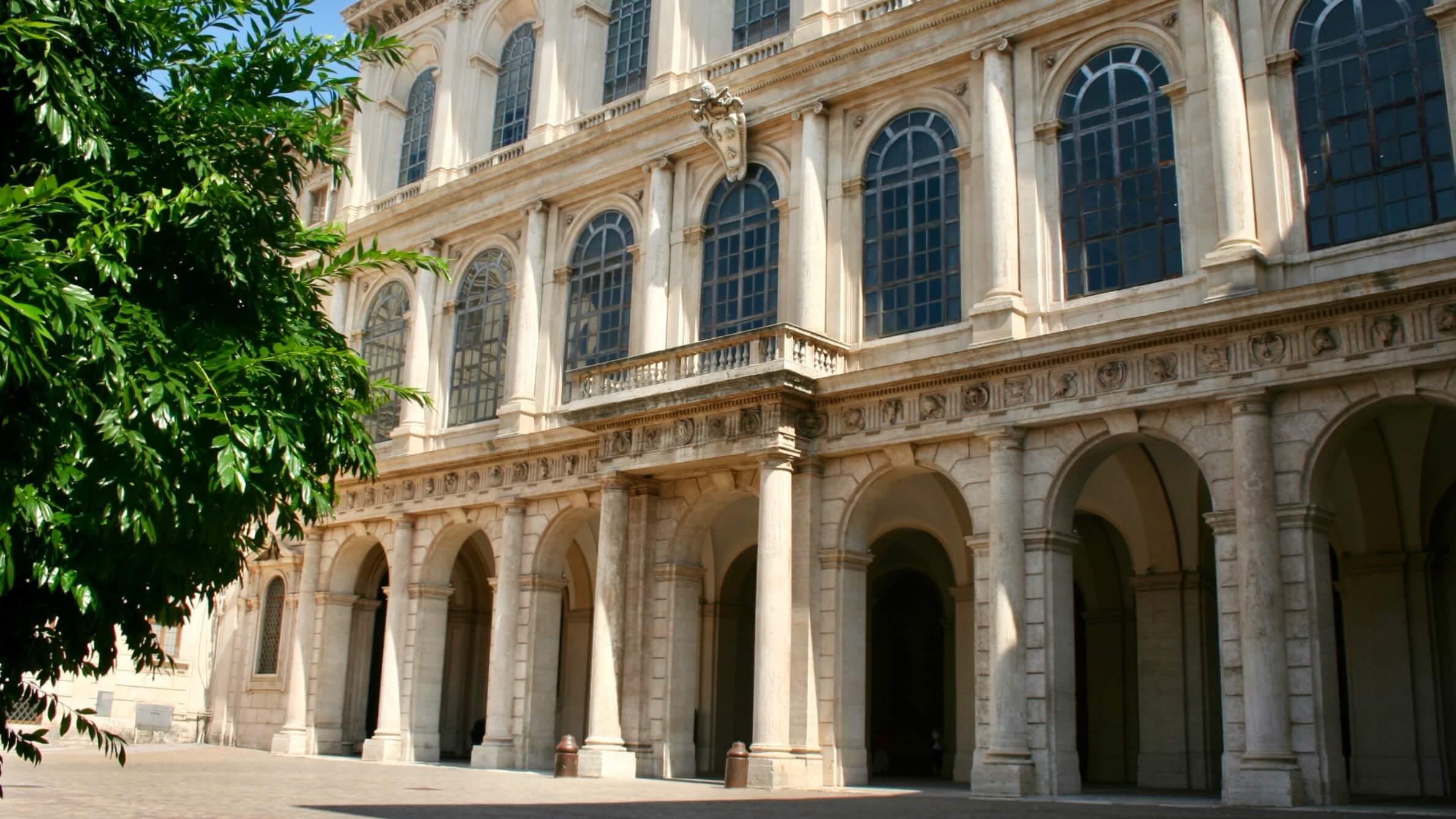

Seeking to combine his love of culture and pleasure with the need to have a base of operations in the heart of the city, Chigi decided to have a ‘suburban villa’ constructed on the banks of the Tiber. Employing the finest architects and painters of the age to bring his plans to fruition, the result was the truly stunning Villa Farnesina – one of the finest testaments to the Renaissance in Rome and premier showcase of Raphael’s art.

Flaunting the norms of the time, Chigi somewhat scandalously lived at the villa with his long-time lover Francesca Ordeaschi, a young Venetian woman from a humble background with whom he shared four children. Finally, Agostino decided to make things official by marrying Francesca in 1519, and it’s in the context of their upcoming nuptials that we need to look at the tale of Cupid and Psyche depicted in the Villa’s airy entrance loggia, framed by fantastical festoons of vegetables, fruits and flowers, where birds flit in and out of the foliage. Guided by the text of Apuleius, let’s look at these extraordinary frescoes in more detail!

The story of Cupid and Psyche is set up like many classic fairy tales. Psyche, the third daughter of a royal household, is possessed of a preternatural beauty ‘so delightful, so dazzling, no human speech in its poverty could celebrate them.’ Rumours soon spread that Psyche is none other than Venus in disguise, and devotees of the goddess quit her temples to pay homage to what they think is her fleshy earthly avatar.

But Psyche’s unearthly good looks cause her nothing but sorrow. Gawped at and admired as one might admire ‘a perfectly finished statue,’ no man would dare approach her asking for her hand in marriage and she came to despise that ‘beauty of form the world found so pleasing.’ Desperate, her parents sought advice from an oracle, whose dark portents lead them to shamefully abandon her to an unknown fate at the edge of a cliff.

And it seemed that the gods too had it in for her. Venus, the vain and haughty goddess of love, soon hears of the neglect of her shrines and abandonment of her cult, and is enraged that the praises due to her are being directed instead to a mere mortal. It must be said that Venus had something of a track-record for jealousy (kickstarting the Trojan war after bribing her way to victory in a beauty contest was just the most notorious example), and here she fully lives up to type.

Calling her son Cupid to her, she tasks him with the ruin of her earth-bound rival. By strategically piercing Psyche with one of his arrows, Cupid is to ensure that the young princess will fall in love with some hopeless and unsuitable oaf, leading to her embarrassment and social demise. Venus points out Psyche from on high, and the winged agent of love sets out after his quarry.

But there’s a snag: Cupid, ‘a winged and headstrong boy’ who by his nature was far from immune to the charms of beautiful women, immediately falls head over heels for his intended victim. Enlisting the help of the Three Graces, Cupid hatches a plan to bring the doomed earthly beauty to his luxurious palace, there to seduce her himself. They make love, and feelings kindle too in young Psyche.

Cupid remains invisible during their lovemaking, and, fearful that the news of their illicit liaison might reach the ears of his jealous mother, cautions Psyche not to seek to see his face or uncover his identity. The horny young god’s best laid plans soon fall apart however, when Psyche is unable to resist sneaking a peek of her paramour’s visage as he sleeps. Cupid abandons Psyche in fright, and sure enough Venus gets wind of her son’s naughty defiance. What’s more, she’s furious.

Venus heads to the goddesses Juno (identifiable by the peacock at her feet) and Ceres, (wearing a garland of ears of wheat) to enlist their help in punishing Cupid and her mortal lover. The pair are less than accommodating, however, seeing little wrong in the actions of the young lovers. The faces of the goddesses here are the direct work of Raphael himself (much of the actual painting in the cycle was left to the great man’s assistants), and their resplendent profiles are amongst the most beautiful profiles that the great master would ever create.

The goddess of love seeks Psyche’s whereabouts in vain across all the lands of the earth. Hopping in her golden chariot, a wedding present from her husband Vulcan, she speeds across the sky borne by teams of white doves to remonstrate with her father Jove, chief of all the gods.

The meeting of Venus and Jove is one of the most charming paintings in the cycle. Venus, nude and exceptionally beautiful, uses her feminine charms to convince her father to allow her to send the messenger god Mercury to announce across the world that there’s a price on Psyche’s head, and that whoever brings her to Venus will earn a reward of seven kisses from the goddess of love as well as ‘one deeply honeyed touch of her caressing tongue.’

Next to their meeting, Mercury himself appears in somewhat startling full-frontal nudity – a sign of the enlightened and liberal climate of Rome in the early 16th century as well as proof of the different rules of decorum that governed the sacred and secular realms. You can recognise the messenger god from his distinctive attributes – the sceptre in his hand, the wings on his ankles and the winged helmet he wears. The prominence of Mercury in the villa’s decorations is significant – as the ancient god of commerce and trade, he was an appropriate guardian for the city’s wealthiest businessman and banker.

Curiously, at this point in the cycle there’s a large gap in the narrative as recounted by Apuleius. In the story, Venus finally gets Psyche into her clutches. After subjecting the girl to various torments at the hands of her thuggish henchwomen Anxiety and Sorrow, Venus decides to stick the knife in further by forcing ever-more-put-upon Psyche to perform a series of seemingly impossible tasks – a trope much beloved by ancient authors.

First she must sort a vast pile of seeds and legumes into separate piles; secondly, she is sent to gather a handful of golden wool from a flock of particularly aggressive magical sheep; next up is collecting a vial of water from a raging torrent sourced straight from hell; finally, in the most difficult task of all Psyche is sent down to the bowels of the underworld itself to collect an ampoule of eternal beauty from the goddess Proserpina.

To Venus’ amazement, Psyche passes all the tests with flying colours – but with a little help from some unlikely sources: a troupe of ants, an anthropomorphic river reed, a divine eagle and a particularly wise tower all lend some invaluable help. After collecting her precious cargo from the underworld, Psyche is borne to heaven on the wings of angels to meet with Venus, which is where the frescoes in the Farnesina Loggia take up the tale once more.

But what of our chastised young horn-god Cupid? Still madly lost in his desire for Psyche, he finally overcomes his fear of his mother’s rebukes and decides to turn to his indulgent grandfather Jove, asking him to set things right. Seeing a bit of himself in the lovelorn youth, Jove tweaks his cheek affectionately and and agrees to convoke a council of the gods to find a way forward.

Mercury, once more in his birthday suit, is tasked with bringing Psyche up to meet her destiny in the celestial realm. For many scholars this scene demonstrates the similar fate of Francesca Ordeaschi, for whom a new world of luxury, possibility, and even immortality is opened up thanks to her upcoming betrothal – an extraordinary change of circumstances for the Roman courtesan as much as it was for the mythical princess of legend.

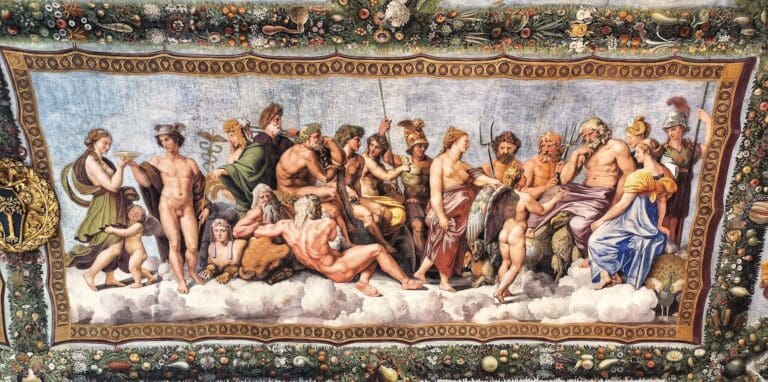

At the centre of the vault, in the first of two large rectangular fields, the gods have all convened at Jove’s command. And what a motley crew they make! Winged Cupid flaunts his shapely rear as he makes his case to a pensieve Jove, a now placated Venus leaning a motherly hand on the youngster’s plumage. All around, a series of muscle-bound old geezers include Neptune, god of the sea, and drunken Bacchus, god of wine.

At the left we recognise Mercury once again, in all his scandalous nudity, who is in the process of handing Psyche a cup of immortal nectar. And so we are apprised of the gods’ decision: by elevating Psyche to the ranks of the gods, the problem of Venus’ injured pride and Cupid’s illicit love for a lowly mortal can both be resolved at a stroke.

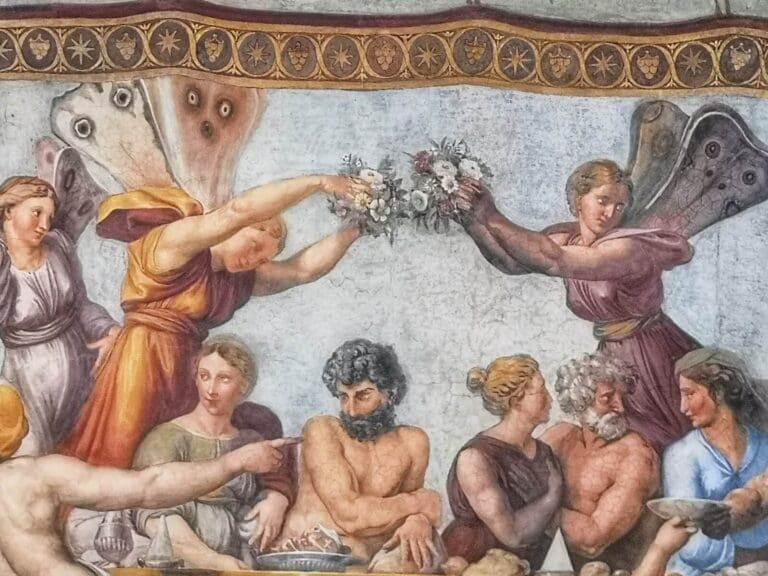

The deed being done, the issues resolved, there was nothing left to do but to have a party. This, the culmination of the elaborate fresco cycle, is the wedding feast of Cupid and Psyche, now joined in divine matrimony. For any contemporary visitor, the parallels between the love-match of the besotted god and a beautiful mortal with that of Agostino and Francesca would have been blindingly obvious. And we can take the link further. The nuptials taking place on Mount Olympus as imaged in the Farnesina are certainly impressive, but the actual wedding and subsequent celebrations that took place right here in Rome on August 28th 1519 were no less opulent, a knees-up for the ages presided over by Pope Leo X Medici himself.

Agostino sadly didn’t last much longer, dying on April 11 1520, just 5 days after the tragically premature death of Raphael himself. But the great temple of art and good taste that they fashioned here more than 500 years ago still still stands as perhaps the finest testament to the world of Renaissance Rome.

Visit this jewel of the Roman Renaissance located in the heart of Trastevere at Via della Lungara 230 from Monday to Saturday, 9am to 2pm. Or to get the most out of your visit, reserve a private tour of the Villa Farnesina in the company of one of our expert art-historian guides!

Book Your Rome Experience