Although a visit to the Sistine Chapel and Michelangelo’s awe-inspiring frescoes is probably at the top of your list of what you need to see at the Vatican Museums, there is plenty more to see in Rome’s most incredible museum. The marvellous frescoes that Raphael painted in what are now known as the Raphael Rooms, commissioned by Pope Julius II at the same time as Michelangelo was working in the Sistine Chapel, provide a unique insight into the culture of the High Renaissance and are a spectacular highlight of the Vatican Museums in their own right. Read on to discover what to look out for in these stunning masterpieces of Renaissance art!

Raphael and the Vatican

Known as the ‘Prince of Painters,’ Raphael was idolised during his lifetime and treated with a reverence enjoyed by few artists before or since. Amazingly precocious, the Urbino-native was recognised for his marvellous abilities as a painter from a very early age. He was apprenticed to the renowned Renaissance artist Perugino (a key figure in the first decorations to adorn the Sistine chapel) when he was a boy, but it wasn’t long before Raphael became famous in his own right.

The pupil soon eclipsed his master, and by the time Raphael was in his 20s his paintings were in high demand all over Italy and beyond. Unlike the cantankerous Michelangelo - the posterboy for the artist as troubled genius, cast adrift from the easy pleasures of the world - Raphael was at ease rubbing shoulders with cardinals and aristocrats, princes and popes. His youthful good looks and charm made him a natural at court, and Raphael soon rose to a position of influence and prominence in the Vatican.

If you’ve joined us in the Sistine Chapel on one of our in-depth Vatican tours, then you’ll know the story of how Pope Julius II cajoled, threatened and bribed Michelangelo to redecorate the papal chapel during his reign. But the insatiable Julius wasn’t content with leaving his patronage there; deciding that his own living quarters weren’t up to scratch, he called on the young hotshot Raphael and his workshop to decorate them with splendid paintings.

It was by this time common practice for Popes to attempt to outshine their predecessors’ commissions, and in this case Julius was surely inviting comparison with the suite of rooms that the Borgia pope Alexander VII had frescoed by Pinturicchio only a decade earlier. Julius loathed his predecessor with a passion, and was apparently unwilling to breathe the same air as the notorious Borgia pope. No doubt he relished the opportunity to upstage him in the fineness of their designs as well (Julius died in 1513, and the work continued under his successor Leo X).

It was by this time common practice for Popes to attempt to outshine their predecessors’ commissions, and in this case Julius was surely inviting comparison with the suite of rooms that the Borgia pope Alexander VII had frescoed by Pinturicchio only a decade earlier. Julius loathed his predecessor with a passion, and was apparently unwilling to breathe the same air as the notorious Borgia pope. No doubt he relished the opportunity to upstage him in the fineness of their designs as well (Julius died in 1513, and the work continued under his successor Leo X).

The four rooms decorated by Raphael and his assistants are known as the Sala di Costantino, the Stanza di Eliodoro, the Stanza della Segnatura and the Stanza dell’Incendio del Borgo, and each is home to some of the most beautifully painted frescoes of the Italian Renaissance.

The Stanza della Segnatura

The Stanza della Segnatura is the most important room in Raphael’s Stanze: the hall was the first to be decorated by the artist after being commissioned by the Pope in 1508, and the frescoes here are considered by many to signal the beginning of the Golden Age of the High Renaissance. The room is named after the Segnatura Gratiae et Iustitiae, the Vatican’s high court that used to sit here in the mid 1500s, but at the time of Julius the stanza was used as a private library. The paintings followed a precise theological programme articulating the importance of Truth and Beauty to humankind.

Raphael’s rational, harmonic style can be best appreciated in the Stanza’s School of Athens, a meditation on the elevating role of reason for the human spirit. Here the ancient philosophers Plato and Aristotle debate the nature of the universe surrounded by other philosophers of the classical world. Plato gestures towards the sky as he declares his belief in the existence of ideal forms beyond the visible world, whilst Aristotle points to the ground, staking a claim for his materialist conception of the nature of being.

Take a close look at the cast of philosophers who crowd the fresco: Raphael painted the figures with the faces of his contemporaries, positioning his own generation as the natural heir to the golden age of antiquity. In Plato’s features we can recognise those of Leonardo da Vinci, whilst Euclid doubles for Raphael’s friend Bramante, one of the great architects of the Renaissance. Heraclitus meanwhile, lounging on the steps in distinctive leather boots, is probably none other than Raphael’s greatest rival, Michelangelo himself.

The story goes that Raphael was so overcome by what he saw in a sneak-preview of the Sistine Chapel that he felt compelled to add this last-minute homage to his rival. Keep an eye out too for the dapper young man in the green cap on the right of the scene who locks his gaze on ours - this is Raphael himself.

On the opposite wall of the stanza, The Disputation of the Holy Sacrament reads like a Christian mirror-image of the School of Athens, expounding on the nature of theological rather than rational truth. The painting unfolds on both heaven and earth: Christ reigns in the celestial sphere, where he is joined by the Virgin and John the Baptist. Key players from both the Old and New Testaments surround them: dam crosses his legs as he chats to St. Peter, whilst Moses holds open the stone tablets of the law entrusted to him atop Mount Sinai as he exchanges a sidelong glance with St. Lawrence.

On the opposite wall of the stanza, The Disputation of the Holy Sacrament reads like a Christian mirror-image of the School of Athens, expounding on the nature of theological rather than rational truth. The painting unfolds on both heaven and earth: Christ reigns in the celestial sphere, where he is joined by the Virgin and John the Baptist. Key players from both the Old and New Testaments surround them: dam crosses his legs as he chats to St. Peter, whilst Moses holds open the stone tablets of the law entrusted to him atop Mount Sinai as he exchanges a sidelong glance with St. Lawrence.

Arrayed around the dove of the Holy spirit, four winged angels hold open the four gospels - the divine word of God is seemingly accessible to the faithful only through the mediation of these holy figures. Illuminating everyhthing is God himself, who appears in a celestial sky of blinding gold, rows of cherubim bursting forth from the clouds like so many rays of divine light.

Beneath, in the world of men, an altar at the painting’s perspective centre plays host to a golden monstrance containing the holy host, the unleavened bread that miraculously transforms into the body of Christ and is the centrepiece of the mass in Catholic religious ceremony. Ascending the steps in their attempts to get closer to the altar, the great theologians and doctors of the Church engage in learned debate about the true nature of the miracle of transubstantiation. One points to the celestial vision in the sky, as another gestures to the earthly presence of God in the sacrament.

Where the School of Athens featured the portraits of Raphael’s fellow artists, amongst the popes and prelates populating the Disputa further famous faces can be made out. Look out for the chiselled features of Dante, depicted in sober profile, wearing a laurel wreath in recognition of his reputation as Italy’s greatest poet. Half-hidden in the pious throng, here too is the hooded form of the firebrand Florentine preacher Savonarola. Burned at the stake only a decade earlier, he is probably included here as a mocking gesture from the Pope towards the hated Borgia Pope Alexander VI, who had ordered the monk’s immolation.

Much lighter in theme, finally, is the room’s third great painting, the Parnassus. Here the Greek god of music Apollo strums cheerily on his lyre on the slopes of Mount Parnassus, surrounded by august poets both ancient and contemporary: look out for blind Homer and Sappho, who holds a scroll bearing her name. Dante features once more, again recognisable ini his distinctive cap and laurel wreath.

The Stanza di Eliodoro

Painted by Raphael and his workshop immediately after work was completed in the Stanza della Segnatura, the Room of Heliodorus functioned as an audience chamber for the Pope, and the frescoes on its walls are all devoted to showcasing the supreme power of the pontiff.

In the Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple Heliodorus steals from Jerusalem’s temple and is duly punished for the breach. As recounted in the Book of Maccabees, the Syrian king Seleucus sends Heliodorus to pilfer the treasures of the temple. The high priest Onias is having none of it, and implores God to intervene, who does so in the form of a rampaging knight who chases the would-be thief out of town. Underlining the message of the fresco, Pope Julius himself watches on from a sedan chair to the left.

In the dramatic Liberation of Saint Peter, meanwhile, the chained apostle is freed from prison by an angel in a blinding moonlit night as the armoured guards snooze on their spears in a divinely-instigated slumber. The scene is painted with jaw-dropping virtuosity, and one of the most memorable in the Raphael Rooms.

The opposite wall portrays the miraculous events of the Mass of Bolsena: according to the narrative, a visiting priest from Bohemia had his doubts about the real nature of transubstantiation (the doctrine according to which wine and wafer transform into the body and blood of Christ during mass) quashed when the holy host he was holding started bleeding Christ’s blood during the ceremony. Pope Julius again has a role, kneeling across the altar despite the fact that the miracle took place in 1263.

More time-bending papal aggrandisement is on show in the Encounter of Leo the Great with Attila, although the identity of the pontiff has changed. This fresco was painted after the death of Julius and the accession of his successor Leo X, who put his stamp on the proceedings by ordering Raphael to depict this scene were his namesake Pope Leo X (with a little help from an airborne St. Peter and St. Paul) miraculously stalled the advance of Attila the Hun’s marauding hordes as they prepared to march on Rome in 452 AD. Unsurprisingly, Leo X has had himself painted in the guise of Leo the Great. Look out for the cityscape of Rome in the background, complete with the Colosseum.

The Stanza dell’Incendio del Borgo

Frescoed during the reign of Leo X, the Stanza dell’Incendio del Borgo was used as the Pope’s dining room, and the decorations recount the events of illustrious previous popes with whom the Medici pontiff shared his name. In each of the frescoes, the popes bear the distinctive features of the reigning Leo rather than his historical antecedents.

Frescoed during the reign of Leo X, the Stanza dell’Incendio del Borgo was used as the Pope’s dining room, and the decorations recount the events of illustrious previous popes with whom the Medici pontiff shared his name. In each of the frescoes, the popes bear the distinctive features of the reigning Leo rather than his historical antecedents.

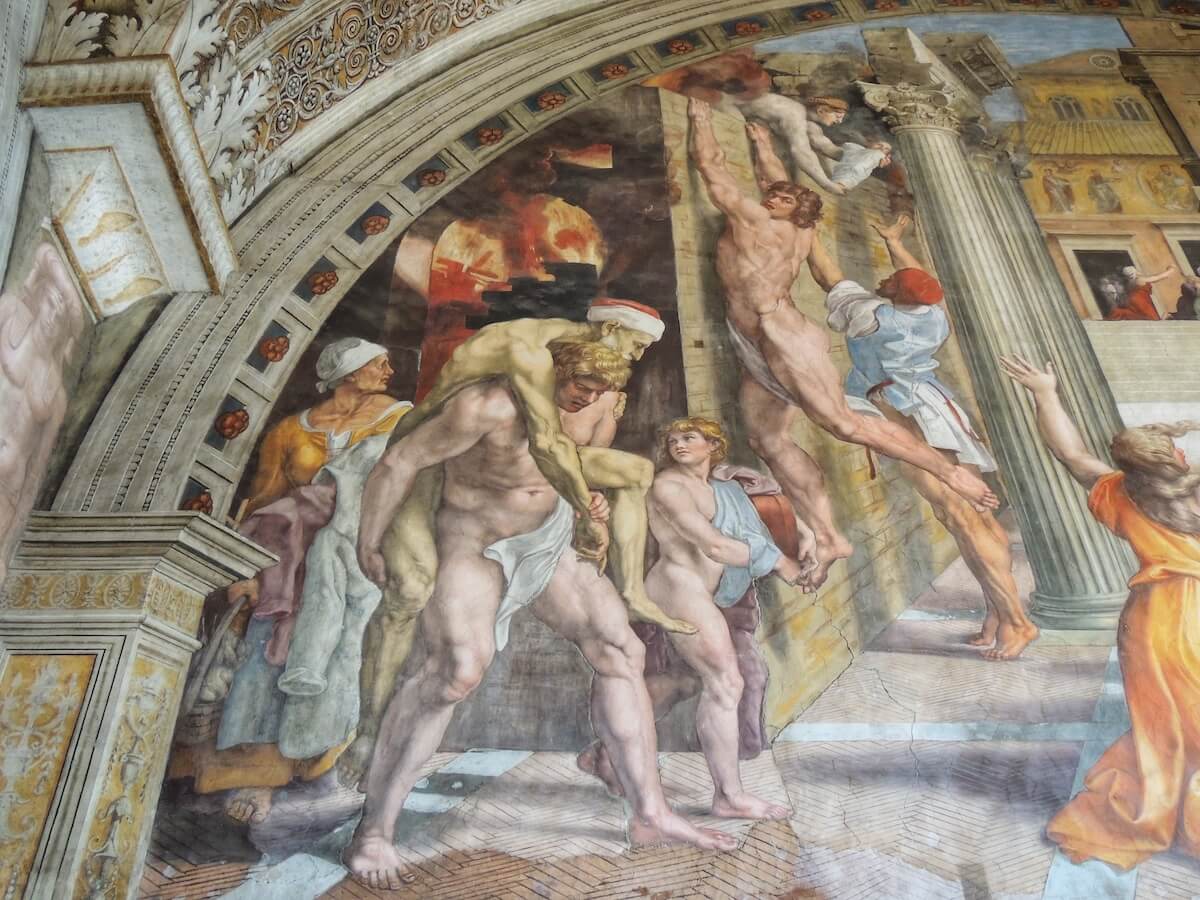

In the painting after which the room is named, the theatrically action-packed Fire in the Borgo depicts a fire in the Borgo, the neighbourhood surrounding the Vatican, in 847 AD. As the city’s citizens desperately flee the flames or fall to their knees in supplication, Pope Leo IV appears on the loggia of old St. Peter’s basilica, quenching the conflagration with a single swipe of his benedicting hand.

Look out for the massively muscular naked man clinging desperately to a wall in the foreground, a clear homage to the art of Raphael’s rival Michelangelo, as well as the young man carrying an elderly figure in a cap on the left: this depicts the Greek hero Aeneas escaping Troy with his father, a key moment preceding the mythological founding of Rome (one of the first masterpieces sculpted by the Baroque master Gianlorenzo Bernini is inspired by Raphael’s group - it’s a must see on a tour of the Borghese Gallery).

The other frescoes in the room see the Battle of Ostia in full flow, where Leo IV’s army defeat the apparently invincible Saracen fleets against all the odds, and the fabulous Crowning of Charlegmagne in which the French king is crowned as the newly minted emperor of the Holy Roman Emperor in St. Peter’s on Christmas Day in the year 800 by Pope Leo III.

The other frescoes in the room see the Battle of Ostia in full flow, where Leo IV’s army defeat the apparently invincible Saracen fleets against all the odds, and the fabulous Crowning of Charlegmagne in which the French king is crowned as the newly minted emperor of the Holy Roman Emperor in St. Peter’s on Christmas Day in the year 800 by Pope Leo III.

The crowning of Charlegmagne would herald the rise of Rome as a powerful force once again in the Middle Ages, but the fresco also had a more contemporary resonance: Pope Leo X had recently come to an agreement with the current King of France Francis I (whose unmistakable portrait takes the place of that of Charlegmagne), heralding a new alliance between church and state.

The Sala del Constantino

The final room to be painted, the decorations of the Hall of Constantine were largely undertaken by Raphael’s assistants to designs by the master after the latter’s untimely death in 1520. Recounting great deeds in the life of the first Christian emperor of Rome Constantine the Great, we first encounter Constantine the night before the decisive battle against his rival Maxentius, when the still pagan emperor is granted a vision of a cross in the sky at his camp accompanied by the inscription ‘in this sign you will conquer.’

The final room to be painted, the decorations of the Hall of Constantine were largely undertaken by Raphael’s assistants to designs by the master after the latter’s untimely death in 1520. Recounting great deeds in the life of the first Christian emperor of Rome Constantine the Great, we first encounter Constantine the night before the decisive battle against his rival Maxentius, when the still pagan emperor is granted a vision of a cross in the sky at his camp accompanied by the inscription ‘in this sign you will conquer.’

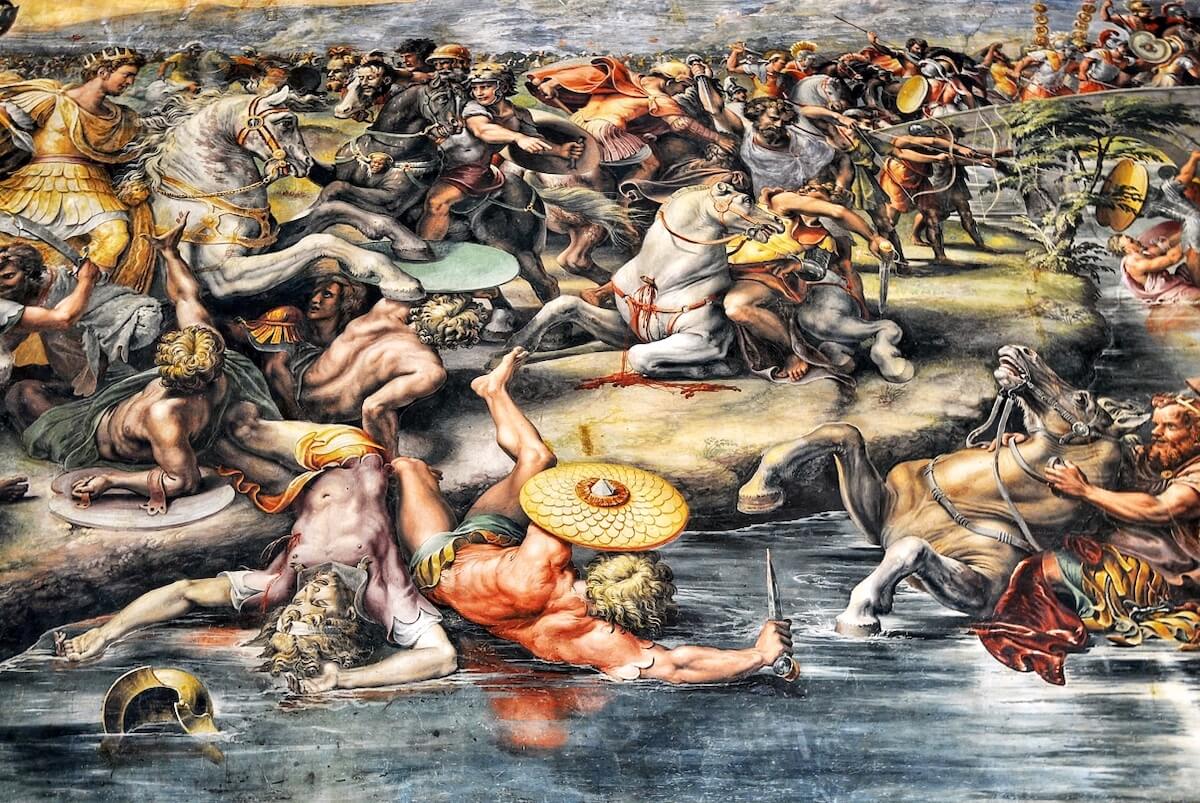

The story continues with the Battle of the Milvian Bridge the following day, one of the most dramatic paintings in the entire suite of apartments. Here a great tangle of bodies and horses combine to form a highly convincing battle scene; the crown-wearing Constantine rides high on a horse at the banks of the Tiber, whilst Maxentius topples desperately from his own steed into the water. The sprawling work was painted by Giulio Romano to drawings executed by Raphael himself.

The final two frescoes in the Sala del Constantino depict Constantine’s ever-increasing ties with the church. The emperor is officially inducted into Christianity in the Baptism of Constantine in the recognisable surroundings of the basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano (founded by Constantine himself).

Finally, Constantine cedes control of the city of Rome to Pope Sylvester in the Donation of Constantine. The emperor is pictured kneeling before the Pope offering him a golden statue, signifying his desire that the church, and not the emperors, would govern the city in the future. The Donation of Constantine was mobilised as a justification for the Catholic Church’s grip on temporal power for centuries. The only problem? The Donation never happened, and the text that documented the event was an entirely fictitious medieval forgery.

We hope you enjoyed our guide to the fabulous frescoes of the Raphael Rooms! If you’d like to see these masterpieces of the Renaissance for yourself in the company of an expert art-historian, then be sure to check out Through Eternity’s range of small-group Vatican tours and private Vatican itineraries!