One afternoon sometime in the 1480s, not far from the Colosseum, the renowned Renaissance painter Pinturicchio was swallowed by the earth. He wasn’t the victim of a rogue sinkhole or out-of-the-blue seismological disaster: Pinturicchio's was a willing descent, a daring journey towards the centre of the earth worthy of Jules Verne’s 19th-century classic of subterranean sci-fi. But unlike the unhinged professor of Verne’s imagination, Pinturicchio didn’t embark on his hazardous spelunking in the name of science.

No, the Umbrian master was after a far greater prize: the long lost splendors of ancient art. This was one of the first times in over a thousand years that mankind had laid eyes on what was perhaps the most amazing and controversial monument of the ancient world, a building that had been revered and reviled in antiquity in equal measure. Pinturicchio was being winched down into the subterranean remains of the Domus Aurea, the emperor Nero’s notorious Golden House.

A Monument to Ancient Decadence

The halls of Nero's Domus Aurea

The halls of Nero's Domus Aurea

Nero’s amazing palace was a vivid symbol of his almost boundless ego. After fire devastated the city in 64 A.D. (famously rumoured to have been started by Nero himself, or at least his henchmen), the emperor had his architects fashion an immense palace consisting of hundreds of rooms.

Scarcely believable highlights included a rotating dining room open to the starry night sky and a massive artificial lake, all built over the charred remains of the metropolis. Just four short years after works began, the palace was already nearing completion: delighted at the progress, Nero famously quipped that here he could finally begin to live like a human being.

Unfortunately for the emperor, his newfound humanity wasn’t to last long. In 68 A.D. Nero’s chequered past caught up with him and he was forced to commit suicide at the tender age of 30, lamenting with his final breath what an artist died in him. Nero’s immense party pad was bulldozed in an attempt to erase the memory of the despised despot almost before the paint had even dried, and his artificial lake filled in: in its place the ancient world’s greatest monument was erected only a few years later: the Flavian amphitheatre, known to posterity as the Colosseum.

The Decorations of the Domus Aurea

Frescoes in the Domus Aurea

Frescoes in the Domus Aurea

The ancient chronicler Pliny tells us that the Golden House had been spectacularly decorated by Famulus, ‘a floridly extravagant artist’ who insisted on always painting in his toga regardless of the jaw-dropping laundry bills this inevitably entailed. The Golden House, as Pliny poetically puts it, ‘was the prison that contained his productions.’

Famulus' fantastically dreamlike paintings were pure flights of the imagination: solid architecture capriciously metamorphosed into willowy plants and tangled flowers; horses were painted with legs of leaves, and unholy animal-human hybrids lurked amidst weird fictional architectures of impossible columns and scrolls, creeping vines and theatrical masks – all rendered in incredibly vivid shades of ancient Technicolor.

With the dismantling of the Domus, it seemed that Famulus’ paintings too were lost forever. But the villa’s destruction wasn’t as complete as it seemed, and in fact much of it remained startlingly intact below the ground - filled with earth, it was adapted as the supporting substructure for the baths complex that the emperor Trajan built on the site. And so it remained, with Famulus’ magical frescoes hidden in their earthen prison for 14 centuries.

The Renaissance Rediscovery of Nero's Golden House

Vivid colors in the Domus Aurea

Vivid colors in the Domus Aurea

We don’t know exactly when the underground remains of the Golden House were finally rediscovered, but by the 1480s the exciting trip downwards was one of the hottest tickets in town. Daredevils, artists, early-modern spelunkers and the incurably curious were all gingerly lowered into the yawning darkness of the abandoned palace through tunnels excavated into the earth.

The palace wasn’t properly excavated until the 18th-century, and the men of the Renaissance instead had to crawl through the uppermost portions of rooms still mostly filled with soil, their noses pressed tight to the curves of the barrel vaults. To move between rooms, they had to literally bore their way through the upper parts of the original walls. But this meant that they got incredible close-up views of the decorations that lit up every wall and ceiling in a way that would have been impossible from the original floor level.

It’s difficult to fully imagine the excitement of Pinturicchio and his colleagues as the narrow flames of their torches flickered and danced over the amazingly preserved frescoes, here a snatch of face revealed, there the yawning maw of some mythical beast.

Early-Modern Graffiti

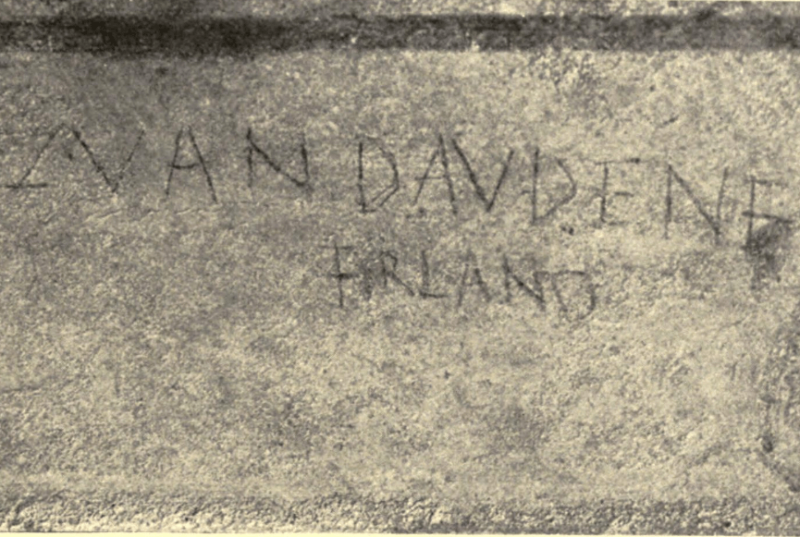

Giovanni da Udine's graffiti signature

Giovanni da Udine's graffiti signature

So awestruck was he by what he saw, Pinturicchio felt compelled to incise his name onto the damp and sweating walls. And it wasn’t just Pinturicchio. All of a sudden the finest artists of the age were obsessively copying and adapting the motifs of the ancient Domus in their own cutting-edge works in Rome, Florence and beyond, from Michelangelo’s teacher Ghirlandaio to Filippino Lippi and Perugino, the master of the young Raphael. Raphael's own student Giovanni da Udine too left his John Hancock down here.

Each made their own perilous journey downward into the dark of the abandoned palace, scrawling their names onto the walls and resurfacing with their minds full of antique inspiration that would change the course of art forever. The rather severe ancient architect Vitruvius had famously complained that with the Domus Aurea the world had fallen prey to a depraved taste for ‘painting monsters in frescoes rather than reliable images of definite things’ - but to the painters of the Renaissance, these shape-shifting monsters were the harbingers of a stylistic revolution.

A Milanese poet perfectly captured the frenzied atmosphere, describing how ‘in every season the rooms of the Domus are full of painters.’ Ironically immortalising the artists’ obsession with this subterranean temple of art, he writes how ‘we crawl along the ground on our stomachs, armed with bread, ham, fruits and wine, looking more bizarre than the grotesques.’

What Influence did the Domus Aurea have on Renaissance artists?

Grotesque decorations by Pinturicchio in Santa Maria del Popolo

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of the rediscovery of Nero’s Domus. This was the first major find of well-preserved painting to come down to the Renaissance from antiquity, and finally artists could see what before they could only visualise from the descriptions of ancient books.

No-one knew that this was actually Nero’s Golden House - most thought it to be instead part of Trajan’s later baths - but whatever it was it offered a window into the world of ancient art that had literally never been encountered before. The splendours of Pompeii were still centuries away from being unearthed, and the decorations’ bright colours and capricious flights of fancy were a world away from the pristine but sterile classicism that the Renaissance had up until now associated with antiquity.

Where can I see Golden House Inspired Artworks in Rome?

Ceiling decorations in Castel Sant'Angelo

Once you know what to look for, you’ll soon start to see these strange ancient decorations everywhere in Rome. It was, naturally enough, Pinturicchio who started the craze, framing a pious image of the Holy Family with the pagan ornament in a chapel at Santa Maria del Popolo. He repeated the trick a few years later in the magnificent della Rovere chapel in Santa Maria Sopra Minerva. In 16th-century Rome there was hardly a palace in the city that didn’t get the ‘grotesque’ treatment, from Palazzo Venezia to the luxurious Villa d’Este in Tivoli.

Even the popes developed a taste for this most pagan of decorations. If you visit Castel Sant’Angelo you’ll see spectacular examples in the fortress’ papal apartments, whilst Raphael himself decorated the Vatican loggias with grotesques that could easily be the work of ancient painters. Perhaps most spectacular of all were the decorations that Pinturicchio provided for the notorious Borgia pope Alexander VI in his own spectacular Vatican living quarters.

As the 16th century drew to a close and a more conservative religious climate descended on Rome, the wholesale adoption of such bizarre pagan taste began to be frowned upon, and the diatribe of the Counter-Reformation Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, in which he described the grotesques as allowing the pagan gods of darkness into the temples of a Christian God hastened their decline. But if you want to get to grips with what drove Renaissance artists in their quest to revitalise 16th-century Rome, then pay attention to these weird designs that snake across the walls and ceilings of palaces and churches all across the city.

Can I Visit Nero's Golden House?

Going underground on a tour of Nero's Golden House

Going underground on a tour of Nero's Golden House

Yes! These days you can get a first-hand look at exactly what so excited Pinturicchio, Raphael and all the rest more than 500 years ago - after a long and meticulous restoration the surviving rooms of Nero’s Golden House are open to visit once again, only on specially accredited tours such as our Domus Aurea Tour.

Today the journey downwards isn’t quite as precarious as the one undertaken by Pinturicchio, and in place of his flickering torch we’ll be armed with the latest in virtual-reality technology that allows us to envisage the Domus in all its original glory. So if you want to walk in the footsteps of the greatest and most adventurous painters of the Renaissance, book your place on our Nero’s Golden House tour today!

MORE GREAT CONTENT FROM THE BLOG:

- The Fascinating History of Nero's Domus Aurea

- How to Visit the Colosseum in 2025

- A History of the Colosseum

- 5 Fascinating Facts About the Colosseum's Arena Floor

- The Colosseum Underground: The Deadliest Show on Earth

- Wild Animals in the Colosseum

- Where to Stay in Rome in 2025: Areas and Hotels Guide

For 25 years, Through Eternity have been organizing expert-led tours to the Colosseum, Ancient City and other amazing sites in Rome. If you're planning a visit to the Eternal City, check out our range of itineraries here!!