Just over 800 years ago, young King Philippe II Auguste (he was just 22 years old) was called to arms by Pope Gregory VIII for the reconquest of Jerusalem. Set to join Philippe on this Third Crusade were Emperor Frederic Barbarossa of the Holy Roman Empire and the king of England, Henry II. While the Germanic Emperor was a source of some irritation, it was the English king who caused Philippe to lose sleep at night. Henry, you see, was also the Duke of Normandy and – through astute diplomacy, dynastic claim, and strategic marriage – controlled the entire western half of the kingdom of France. As duke, Henry might technically owe fealty to King Philippe, but in reality he conducted his own policy, usually to the detriment of the French king.

Philippe put off his departure for 3 long years, during which he constructed a formidable fortress to protect Paris from any threat of incursion from the northwest. According to the most common theory, the castle (or château) was built on the spot of an old barracks for hunters whose job it was to protect the crops and livestock to the west of the city from roaming wolves. The French word for wolf is loup, the hunters’ quarters were referred to as the louvrerie, and this, according to legend, is how the Louvre got its name.

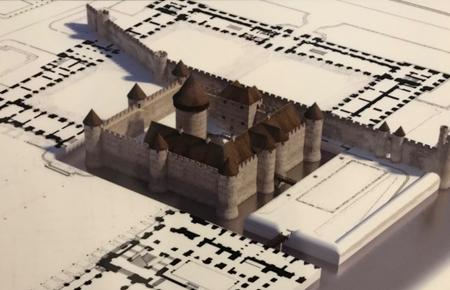

Just before setting off for the Holy Land, King Philippe arranged for the construction of imposing defensive walls around the entire city, with the great château du Louvre at the western extremity on the right bank of the River Seine. This was no luxury palace. It was effectively an army base, with a mighty tower rising high into the sky from the central courtyard of the compound. Another similar series of structures was built along the eastern walls, the château de Vincennes. (It’s still there, by the way, the gothic glory of the central tower nearly intact. It is certainly worth a visit and is easily reachable by RER A (Vincennes) and Metro Line 1 (Château de Vincennes, the western terminus.) The Louvre complex was mighty indeed. It covered an area 72m by 78m (236ft x 256ft), had 10 great towers surrounding its walls, with the central tower (in French, donjon, which is the source of the English word dungeon) rising up a staggering 32m (105ft).

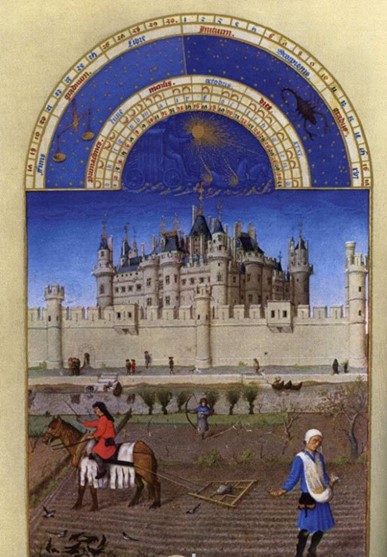

Throughout this period and into the early 1500s, the royal residence in Paris was the Palais de la Cité (the City Palace). It was located on the Ile de la Cité, the island at one end of which stands the cathedral of Notre Dame. By the middle of the 14th century, Paris had outgrown its walls, wrapping itself around the old Louvre fortress. King Charles V, though retaining the island palace as the principal royal residence, decided to convert both the château de Vincennes and the château du Louvre into swish kingly suites. The exterior was softened as well, taking on the appearance of a fairytale castle. The results of Charles V’s remodeling can be admired in the Limbourg Brothers’ magnificent early 15th-century calendar, Les très riches heures du duc de Berry. The month of October shows scenes of autumn harvest outside the walls of the city, with the creamy white stone and blue-tinted towers of the Louvre proudly proclaiming the glory of France and her king.

François I and the Sweet New Style

A hundred years later, King François I chose the Louvre as his principal residence, making substantial alterations that reflected his admiration for the innovations of the Italian Renaissance. He had ascended to the throne in January 1515 at the tender age of 20 and immediately pressed his dynastic claim to the duchy of Milan. In this endeavor, François was wildly successful, clinching the decisive victory in September of that same year, just about the time he was celebrating his 21st birthday. The diplomatic groundwork for an accord granting papal recognition of the conquest was laid in the northern Italian city of Bologna in December 1515.

Accompanying Pope Leo X as part of his entourage was 64-year-old Leonardo da Vinci. Through various encounters and conversations, the young French king eagerly absorbed the great Florentine master’s ideas on everything from art and architecture to military technologies and flying machines. Upon François’ invitation, da Vinci relocated to France, taking a few dedicated students, faithful friends and the portrait of a certain Monna Lisa Gherardini with him. Over the next 3 years, the final ones of da Vinci’s life, King François plumbed the depths of the great man’s knowledge, feverishly applying what he was learning to his various residences. Da Vinci left 4 paintings in addition to the Mona Lisa, as well as 22 drawings, to the French king. This work, now housed at the Louvre, constitutes the largest collection of works by da Vinci anywhere in the world.

In 1546, King François engaged an architect to oversee the monumental project of transforming the Louvre into a royal residence that reflected the luxury and opulence of the great Renaissance palaces he had seen in Italy. Unfortunately, François died the following year. It would fall to his son and heir, King Henri II, to complete his father’s work.

The effects can be most magnificently appreciated in the Louvre’s Room of the Caryatids. Enormous windows were installed to flood the hall with light, and a broad arched ceiling served to heighten the sense of open space. There had certainly been no lack of fine art in the royal residence before this, but it had always been used merely as decoration. Now entire rooms were given over to the display of art, from ancient statuary to paintings in what the pope in Rome was calling il dolce stil novo, the sweet new style.

Diana, Goddess of the Hunt

Dominating the center of the Room of the Caryatids is an imperial Roman copy of an earlier Greek bronze original of Artemis accompanied by a doe. A gift from Pope Paul IV to King Henry II, it seemed to be a cheeky wink and a knowing nudge referencing the king’s mistress, Diane de Poitiers. In fact, it originally stood prominently in the Queen’s Garden at the château de Fontainebleau to the southeast of Paris. One can only imagine the irritation of Henry’s queen, Catherine de’ Medici, who indeed spent quite a lot of time here, where she gave birth to most of their 10 children. This elegant and powerful vision of Diana, among the very first ancient statues to be brought to France, was considered to rival even the best pieces in the Roman collections at the remarkable Villa Borghese and the Vatican palaces themselves.

As Queen Mother, Catherine de’ Medici had the new Tuileries palace built west of the Louvre. Her son-in-law, King Heni IV, connected the two palaces with a Grand Gallery more than half a kilometer long. Though Louis XIV transferred the court to Versailles, he still contributed to the ongoing modernization and beautification of the Louvre. He permitted the former royal apartments to be used by a series of newly-created Academies (e.g., the Academy of Sciences, the Academy of Painting and Sculpture, etc.). Eventually, even the extensive Grand Gallery was converted for use as studios for artists to live and work in, a kind of incubator for talent and experimentation.

It was in the final years of the reign of Louis XVI and his consort Marie-Antoinette that the project of establishing a properly curated museum within the Louvre was developed, though the project was fated to be realized only after the fall of the monarchy. In fact, the new Central Museum of the Arts of the Republic was officially opened to the public on 21 September 1793, on the first anniversary of the vote in the National Convention that gave birth to the First Republic. The new museum’s principal exhibits were installed in the Grand Gallery, featuring elements from the former royal collections, including the Mona Lisa and the sculpture of Diana, Goddess of the Hunt – both taken from Versailles – as well as some recent additions to the State’s treasures.

Michelangelo’s Slaves

In Rome almost 3 centuries earlier, Michelangelo had given a certain Roberto Strozzi from Florence two sculptures that had been intended for Pope Julius II’s tomb but ultimately rejected. After a long perigrination, they had found their way into the collections of a descendent of the (in)famous Cardinal Richelieu. In a bid to make money for a presumptive escape from the dangers of the French Revolution, the wife of the last Marshal of Richelieu attempted to sell them. The government got wind of this and swooped in to arrest the poor woman and confiscate her precious property. Thus did the great master’s Dying Slave and Rebellious Slave find themselves on display in the halls of the Louvre.

The tumultuous 19th century brought the triumphs and the tragedies of the Napoleonic era, the great social movements of the 1830s and late 1840s, and the theatrical return of the Bonaparte dynasty. Inevitably, these events were reflected in the arts, sometimes offering bitter commentary. There is no better example of this than Théodore Gericault’s heartbreaking canvas depicting The Raft of the Medusa. The collapse of the Napoleonic regime in 1815 led to the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, whose king and councilors proved to be not only inexperienced bit tragically inept. The wreck of the naval frigate Medusa, caused by the arrogance and ignorance of its captain, left 147 people adrift on a makeshift raft for 13 days. Only 15 survived. The desperation and despair of the innocent victims of incompetence served as a fitting metaphor for the shipwreck of state under Louis XVIII.

This period also saw the expansion of the nation’s military, political and economic influence around the globe. France was now in prime position to capitalize on Europe’s fascination with the cradle of Western Civilization. French archeologists led some of the most ambitious digs in the Mediterranean world and brought home works of ancient art that still beguile us today. The Venus de Milo has been prominently displayed at the Louvre since shortly after she was discovered in 1820, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace has graced the grand stairway of the museum since 1884. These sculptures, both from the 2nd century BCE, are radically different female figures, depicting almost diametrically opposed attitudes and emotions. There is, though, a remarkable convergence, each one complementing the other. The triumphant winged Victory is eminently graceful in her overwhelming power, while Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, is undeniably powerful in this posture of sensuous grace.

With these magnificent women – indeed, with everything that we see and experience at the Louvre – we are reminded of the complexity of the human experience and of the ties that bind us to our ancestors. In an entirely modern idiom, the pyramids in the Napoleon Courtyard of the Louvre call us to be informed by our past but never imprisoned by it. The structure of a pyramid, evocative of ancient Egypt, is one of the most stable in the physical world. This teaches us that without knowledge, understanding and appreciation of our history, we are anchorless and rudderless in the turbulent seas of life on Earth. The spectacular glass and steel of these particular pyramids, though, point us onwards and upwards into our future. At the heart of the Louvre, the very embodiment of the identity of a nation rich in history and ripe with potential, it is difficult to imagine a more fitting image.