Home to arguably the greatest collection of mosaics anywhere in the world, Ravenna is an absolutely unmissable stop for art-lovers on a trip to Italy. The series of churches and baptisteries that house these precious artworks are testament to Ravenna’s glorious golden age at the tail end of the Roman empire, when the Imperial capital was moved here in 402 AD. Despite the decline and fall that the Roman world was suffering in this period, the glories of Ravenna remained undimmed for fully three centuries, and the architectural and artistic remains from this time provide the most fascinating documentation of the tumultuous phase between the heyday of the Roman empire and the rise of medieval Europe.

From eastern empresses to Gothic warriors, Roman senators and heretical bishops, a diverse cast of characters were responsible for the unique cultural heritage that has led the city to be justifiably inserted on the Unesco World Heritage list. Discover them with us this week as we find out where to see the incredible mosaics of Ravenna!

The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia

The figure of Galla Placidia looms large in the story of Ravenna’s transformation into an Imperial capital in the 5th century AD. The daughter of Emperor Theodosius I, the princess was kidnapped and made hostage by the invading army of the Ostrogoth king Alaric, and married to the general Ataulf. After various vicissitudes, killings and conspiracies, Galla Placidia was returned to the protection of her brother Honorius, who married her off to his general Constantius III. Constantius rose to the position of emperor before dying in 421, leaving Galla Placidia as Empress of the Western Roman empire.

Although Galla Placidia’s power waned somewhat when her son Valentinian III came of age, she remained an important figure in the Imperial court and adorned Ravenna with magnificent sacred and secular buildings, throughout her life. Amongst these is the building erroneously known as the mausoleum of Galla Placidia. In fact, the edifice originally served as a church for the Imperial palace, and only came to house her tomb centuries later (or according to some sources not at all - the identity of the figures in the three monumental marble sarcophagi is open to dispute).

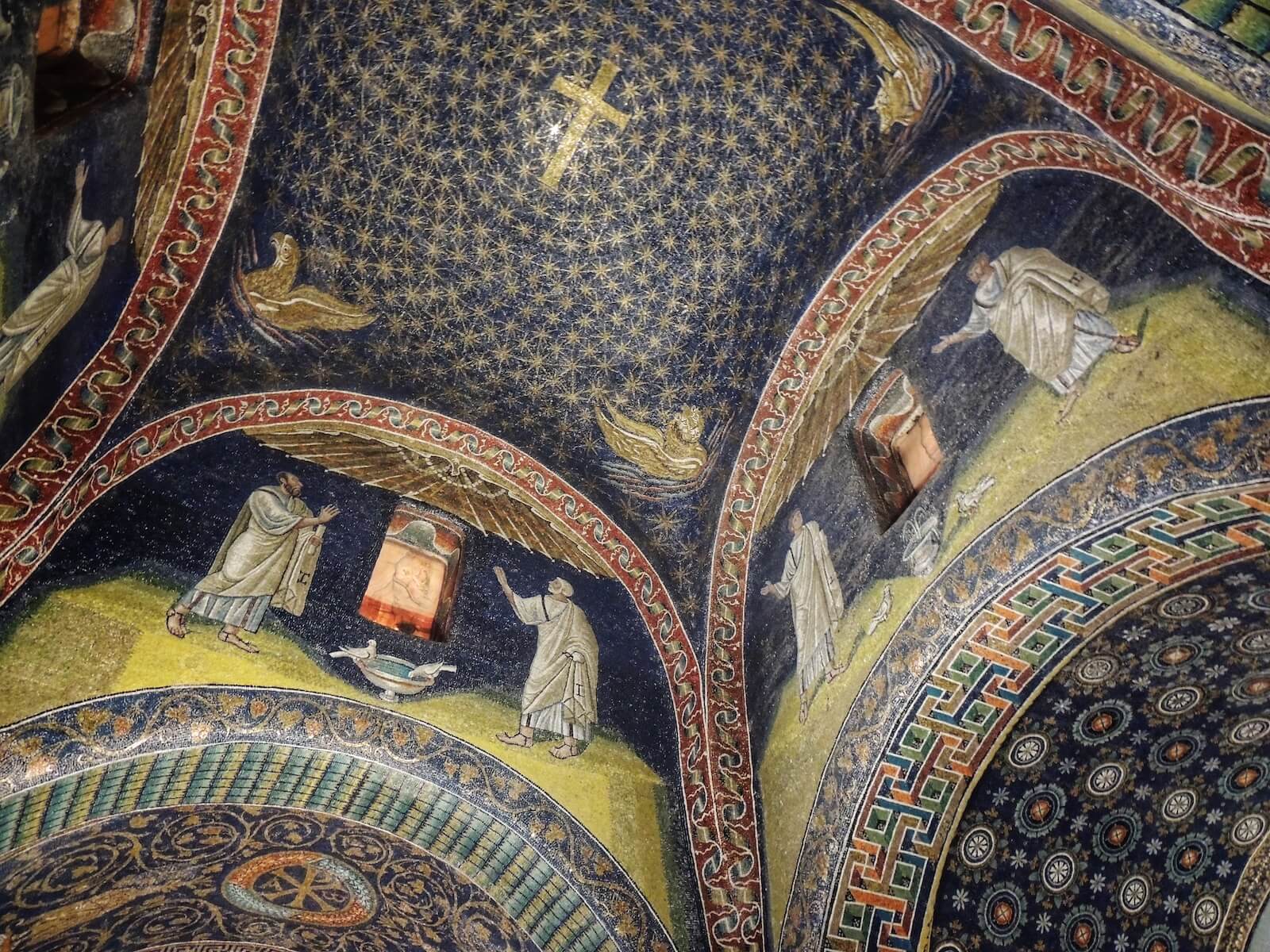

The simple, rather austere brick exterior gives little clue as to the opulent decorative delights that lie in wait within the cross-shaped edifice, where splendid mosaics cover every inch of the interior. The simple barrel-vaulted roof seems to transport us to another world: a deep blue ground of azure tiles is punctuated with white daisies and circular motifs of red, green and blue, like some abstract vision of a divine meadow.

Rich festoons of flowers and overflowing baskets of fruits meanwhile express an extraordinary superfecundity. Above the entrance, a narrative mosaic depicting Christ in the guise of the good shepherd surrounded by his contented flock in a pastoral landscape makes clear that he is the source from which all this abundance springs.

More celestial visions take place in the apse, where a dizzying array of golden stars surround a cross on another midnight blue sky as the emblematic animals of the Evangelists look on. More toga-clad apostles gesture from the lunettes below, awaiting the second coming of Christ. At their feet, white doves slake their thirst from flowing fountains. The spectacular details, vibrant colours and superb craftsmanship of the tiny tesserae make the mosaics of the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia unforgettable.

The Neonian Baptistery

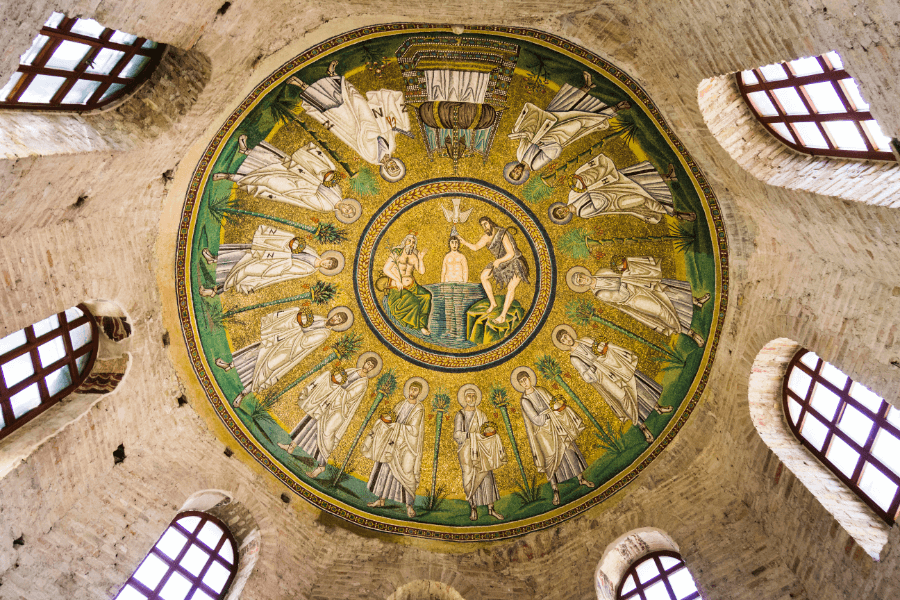

Also known as the Orthodox Baptistery, this beautiful octagonal brick building is the most ancient building still standing in Ravenna. Scholars think that the edifice originally formed part of a Roman baths complex, before the bishop Orso transformed and adapted it into a dedicated baptistery adjacent to the grand basilica (now sadly destroyed) that he built here at the end of the 4th century. Construction wasn’t completed until about a century later, however, when the bishop Neone added the dome, with its extraordinary mosaic decorations.

Appropriately enough, the mosaic in the cupola centres around a representation of Christ being baptised in the river Jordan by John the Baptist. Interestingly, the river itself is personified by a very pagan-looking river god. Surrounding the central roundel is a procession of the twelve apostles, each carrying a crown of martyrdom and identifiable by an inscription in gold lettering by their heads. The figures are highly classical in appearance, and remind us that at this early stage the line between Christian and Roman art had not yet been drawn. Also classical is the fictive architecture that covers the walls beneath the apostles, strongly recalling the frescoes of Pompeii.

The Arian Baptistery

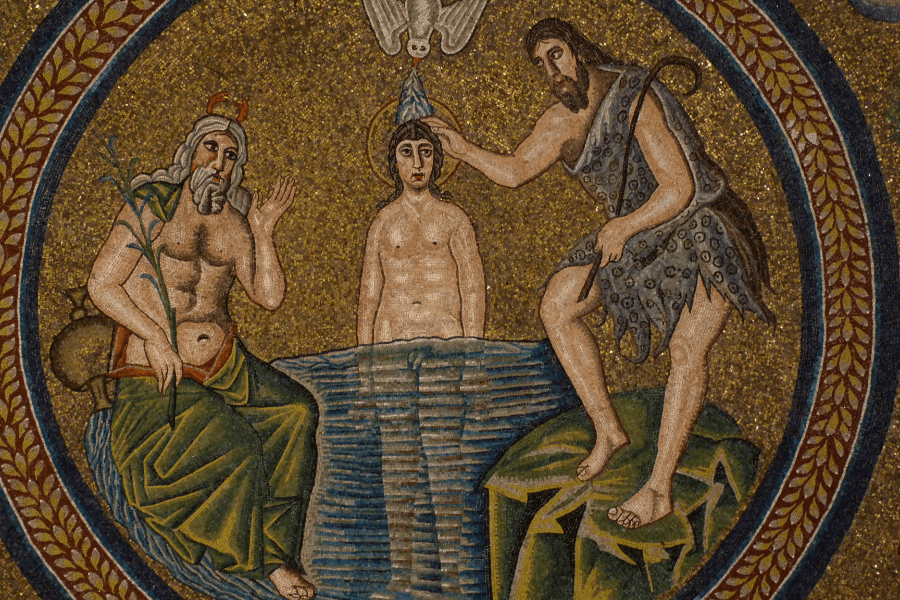

The highly complex and changeable political climate that characterised Ravenna in late antiquity had an impact on the city’s architectural fabric. When the Gothic king Theodoric took control of Ravenna in the year 493 after splitting his rival Odoacer in two at a feast, he had a number of monuments built in the city to ensure his legacy. Theodoric and his tribe followed the Arian branch of Christianity (a theology that was later declared heretical by the church for its elevation of God the Father above Christ in the holy hierarchy), and so the king commissioned a new baptistery to cater for them.

Like the nearby Neonian baptistery, the Arian baptistery is octagonal, and features equally impressive mosaic decorations within. Once again we see John the Baptist, clad in his distinctive animal skins, baptising Christ at the centre. The youthful messiah is naked and immersed to the waist in the waters of the river Jordan as an elderly but impressively built river god watches on.

The Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo

Initially built as a grand house of worship for the Arian church under Theodoric at the start of the 6th century, the church of Christ the Saviour was reconsecrated to the Catholic rite and dedicated to Saint Martin in the year 561, and only received its current denomination of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo with the arrival of the relics of Ravenna’s first bishop Apollinare in the 9th century. Despite its shifting identities, the basilica remains a glittering testament to the splendours of Theodoric's hybrid Romano-Gothic court.

The airy interior features a wide nave and two side aisles, divided by 12 Greek marble columns. But it is the decorations above the arcades that most visitors come to see - and for good reason. The tiers of glittering mosaics conferred upon the church the moniker of ‘The Golden Heaven’ shortly after its construction, and so dazzling are they that according to legend Pope Gregory the Great ordered that they be dulled down because they were distracting the congregation. But nothing could dim their lustre.

All along the upper tier of the left wall, 13 rectangular mosaics depict scenes from the miracles and parables of Christ, part of Theodoric's original decorative campaign. Fascinatingly, for those of us used to the mature, bearded Jesus familiar from the Middle Ages and Renaissance, here Christ is a callow, clean-shaven youth clad in a toga of Imperial purple. Look out for the Wedding Feast at Cana, Peter and Andrew fishing, and the Resurrection of Lazarus amongst other vibrant scenes.

Across the nave on the right hand side on the same level, scenes from the Passion and Resurrection of Christ continue the story. Highlights include a Last Supper where the apostles are arrayed around a massive platter of fish, as well as exceptionally dramatic envisionings of the Kiss of Judas, Pilate washing his hands and Christ on the way to Calvary.

In the register beneath the narrative scenes from Christ’s life 16 massive, statuesque figures of saints and prophets flank the windows of the basilica. Once again, the worlds of Ancient Rome and Christianity combine in these austere bearded figures, clad in white togas like so many Roman senators.

In the lowest and largest register, we encounter the most famous mosaics in the church. To the left, a stately cortege of early-Christian virgin martyrs, dressed in the sumptuous finery of Byzantine princesses with jewel-studded cloaks and headdresses, carry crowns and palms towards the enthroned figures of Christ and the Virgin Mary. They are joined by the figures of the three magi, the exotic kings from the east who bring offerings of gold, frankincense and myrrh to the newborn Christ. Facing them on the right side of the church is another procession, this time of 26 male martyrs making their way towards a stately Christ seated on a throne flanked by angels.

Near the entrance, two fascinating depictions of urban spaces face each other: on the right is Theoderic’s opulent palace, a splendid and complex edifice of columns and arcades, bright red roofs and fluttering curtains - portraits of Theodoric and his retinue were replaced by the curtains when Arianism was denounced the following century. To the left, meanwhile, is the port city of Classe, its high walls glittering with gold as three ships lie at anchor in the nearby bay.

The Basilica of San Vitale

In the apse mosaic of the spellbinding Basilica of San Vitale, the bishop Ecclesius proudly presents a model of the revolutionary domed church that he first commissioned in the final years of Theoderic’s reign to an indulgent Christ seated on a globe. Although Ecclesius was a Catholic, the Arian king pursued a policy of religious toleration which meant that commissions like this destined for the city’s Catholic community could go ahead. And so with the aid of a massive bequest of 26,000 soldi from the money-changer Giuliano l’Argentario, around the year 530 Ecclesius set about constructing a house of worship dedicated to local saint Vitalis, inspired by the grandiose buildings he had seen on diplomatic missions to Constantinople.

Standing opposite Vitalis, Ecclesius looks justifiably smug about his exalted position in Ravenna’s most impressive church; but the bishop sadly wouldn’t live to see it completed. Work continued under the bishop Victor and finally Archbishop Massimiano (who also features in the decorations) after his death; but more importantly for the story of Ravenna was Theoderic’s own demise after more than 30 years of rule, which led to a decade of strife before the troops of the Eastern Emperor Justinian captured the city under the command of general Belisarius, ending Gothic control of Italy.

These events are captured in the most famous mosaics in the church, stunning twin portraits of the emperor Justinian and the Empress Theodora alongside their courtly retinues that have done much to define the visual trappings of power in art ever since. Despite the stunning details of their portraits and costumes, however, the Imperial couple never actually set foot in their new dominion. The man who did the dirty work on the ground, Belisarius, also features.

Every surface of San Vitale glitters and shimmers with countless designs, narratives and motifs picked out in thousands of tiny coloured tiles. Look out for the scenes from the Old Testament, including Abraham readying himself to sacrifice his son Isaac and Cain’s murder of his brother Abel. The works are all of the highest quality, and rival the craftsmanship evident in the most exalted early-Christian churches in Rome and Constantinople - vivid symbols of Ravenna’s key role in these febrile years.

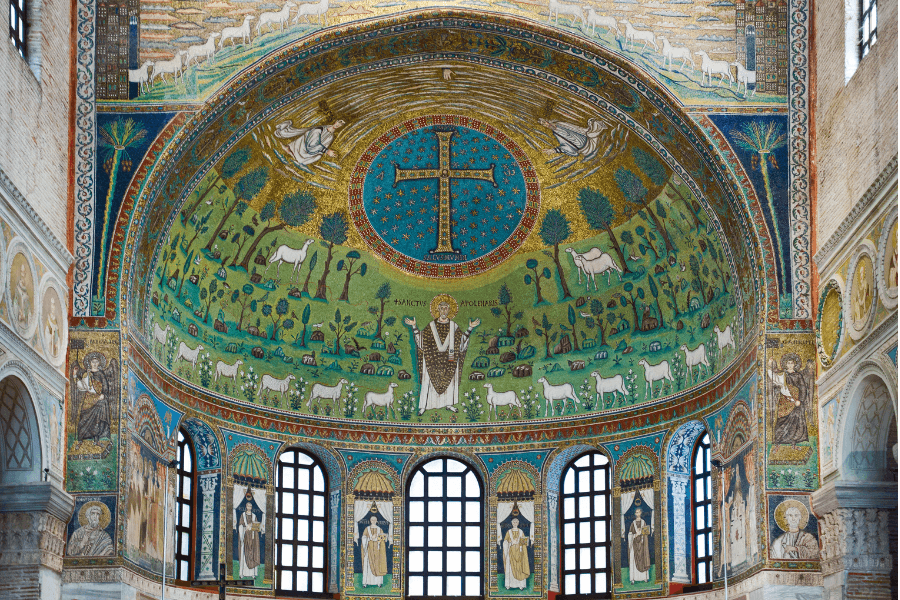

The Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe

Situated five kilometres outside Ravenna, the massive paleo-Christian basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe was commissioned by the bishop Ursino in the middle of the sixth century, and financed by the massive wealth of the banker Giuliano l’Argentario, who also ponied up the cash to fund the construction of San Vitale.

The church was built to glorify the burial site of Ravenna’s patron saint, and like the church of Sant’Apollinare, the beautiful light-filled interior consists of a wide central nave divided from side aisles by marble columns. Originally the walls would have been covered by precious marbles, which were stripped and stolen by the unscrupulous Sigismondo Malatesta to be re-used in Leon Battista Alberti’s Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini.

Today the most impressive artworks in the church are the mosaics in the apse. Christ and the zoomorphic animals of the Evangelists watch from the Triumphal entrance arch. In the niche below, the hand of god descends from the heavens towards a massive gem-studded cross on a blue field punctuated by 99 golden stars. Saint Apollinare himself appears directly beneath the cross, arms raised in prayer and standing in the midst of a lovely green meadow rich with cypress, pine and olive trees as well as daisies, lillies and other flowers. He is surrounded by twelve sheep - the apostles of Christ.