500 years ago today, on April 6th, 1520, the world of art lost one of its favourite sons. Struck down by a fever at the peak of his powers at just 37 years of age, the extraordinary perfection and unmatched realism of Raphael’s paintings ensured his reputation alongside Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci at the summit of the pantheon of Renaissance art, shining exemplar of the heights that human creativity scaled during a glittering Golden Age. To celebrate the 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death, we’ve come up with a virtual guide to the master’s artworks in the Eternal City.

The Prince of Painters

For contemporaries, Raphael was more than just a painter. One of the first true superstars of the art world, the man that history would come to know as the “Prince of Painters” was widely thought to be touched by the hand of the Divine himself. Shortly after Raphael’s death, a poem penned by Antonio Tebaldeo summed up the superhuman esteem in which he was held: “What wonder if you, like Christ, perished in the fullness of your days? That one is the God of Nature, while you were the God of Art.”

Raphael’s popularity was almost universal during his lifetime; handsome and eloquent in equal measure, the painter was blessed with an easy charm lacking in his great rival Michelangelo, perfectly at home in the rarefied company of the popes and princes who commissioned him to beautify their palaces and chapels. Born into the world of the Renaissance court in the spectacular hill town of Urbino, from his earliest years the precocious Raphael was amply endowed with the gentilezza required of the Renaissance courtier.

After a highly successful apprenticeship with the Umbrian master Perugino, the ambitious Raphael naturally made his way south to Rome and the Papal Court of Julius II, who was to become arguably the greatest patron of art the Renaissance had ever known. Rome was kind to the young painter, who was destined to spend the remainder of his life here. Before contracting the mystery illness that cut him down in his prime, Raphael had left behind a string of masterpieces in the Eternal City.

Many of them still survive in their original surroundings 500 years after his death, and traipsing through Rome in search of Raphael’s iconic artworks is one of the Eternal City’s greatest pleasures. As you can’t make it to Rome right now to toast half a millennium of Raphael’s enduring legacy in person, we’ve come up with a virtual guide to the master’s work in the Eternal City.

1. The Raphael Rooms, Vatican Museums, 1508-1520

In 1508 Raphael, still only in his mid 20s, was given the opportunity of a lifetime:

Not content with commissioning Michelangelo to redecorate his private Sistine Chapel, the worldly Pope Julius II decided that his own apartments weren’t up to scratch, and so called on Raphael to adorn them all over with frescoes. Julius was keen to upstage the suite of rooms that Pinturicchio frescoed for the notorious Borgia Pope Alexander VII only a decade earlier, whom Julius loathed with a passion. Raphael was to amply repay his faith.

The huge commission was to make Raphael’s career, and the paintings that he came up with to adorn the suite of 4 rooms – the Stanza della Segnatura, the Stanza d’Eliodoro, the Stanza dell’Incendio and the Stanza di Costantino - would occupy him on and off for the remainder of his life. Running the gamut from historical scenes lauding the limitless power and authority of the Pope to contemplative allegories of learned humanist endeavour, Raphael’s Vatican frescoes are the most vivid evocations of life at the Renaissance court in existence.

Each of the works that adorn the walls of the Raphael Rooms are masterpieces in their own right, but the Stanza della Segnatura’s iconic School of Athens is the undisputed showstopper. In the deeply recessed fictive space of a magnificent but apparently unfinished classical structure – probably meant to invoke the new St. Peter’s Basilica that was being constructed by Raphael’s friend Bramante nearby - dozens of ancient philosophers are locked in debate concerning the nature of knowledge and being.

At the centre, just at the perspectival construction’s vanishing point, are the unmistakeable figures of Plato and Aristotle. Plato points towards the sky, indicating his belief in a world of ideal celestial forms; Aristotle meanwhile gestures stubbornly downwards towards the ground in demonstration of his materialist terrestrial philosophy. One of the most fundamental fault-lines of Western philosophy summed up in just a few, masterful brushstrokes.

It seems that Raphael couldn’t resist painting the philosophers with the faces of his contemporaries, linking Renaissance thought with classical ideals: Plato bears the features of Leonardo da Vinci, whilst the great geometer Euclid has been cast as Bramante, whose own grasp of geometry was fundamental to Renaissance architecture.

Michelangelo meanwhile makes an appearance as the melancholy Herodotus lounging on the steps in the foreground. The story goes that Raphael was so overcome by what he saw in a sneak-preview of the Sistine Chapel that he felt compelled to add this last-minute homage to his rival. One portrait is not in doubt – the dapper young man in the green cap on the right of the scene who locks his gaze on ours is Raphael himself.

Tip: Other frescoes in the suite of apartments are hardly less impressive. The Expulsion of Heliodorus and Fire in the Borgo ushered in a new language of dramatic drama, whilst The Liberation of Peter from Prison is a masterpiece of darkness and light - the ultimate expression of the chiaroscuro technique in Renaissance art.

2. The Deposition, Galleria Borghese, 1507

As the 16th century dawned over the rolling Umbrian hills, Perugia was in a ferment. The Baglioni and Oddi families were engaged in a brutal turf war for control of the city, and their bitter rivalry was spilling out onto the city streets. Blood was being shed with alarming regularity, culminating in the knifing of the thuggish young Baglione scion Grifonetto in broad daylight one July day in 1500 at the hands of his own cousin Gian Paolo (in mitigation, Grifonetto had attempted to murder his assailant and much of his family the night before in a failed family coup).

Grifonetto bled out in the arms of his weeping mother Atalanta, who moments before had refused him refuge so disgusted was she by his family betrayal; still grieving, some years later she called on Raphael to paint an altarpiece depicting the Entombment of Christ for the family chapel in Perugia’s San Francesco al Prato in honour of her murdered son.

The young Raphael jumped on the chance to paint a large-scale narrative painting, the istoria which was the height of painterly ambition according to Leon Battista Alberti’s theory of Renaissance art. After an innumerable series of preparatory drawings, the final composition Raphael came up with was as original as it was unforgettable.

Two men struggle mightily with the dead weight of Christ in the foreground as they haul his body off to the tomb from the distant hill of Golgotha, where the crosses of martyrdom are still visible in the background. A series of biblical figures express varying stages of grief around the Messiah’s lifeless body. Beautiful Mary Magdalene takes Christ’s hand in hers with an expression of infinite sadness; St. John stares at the empty eyes of Jesus, his hands clasped in prayer, whilst the elderly Nicodemus involves us in the ancient scene by fixing us with his penetrating and despairing gaze.

Most touchingly of all, the Virgin Mary collapses in a swoon of anguish, entirely overcome by the sight of her dead son – the scene must no doubt have evoked in Atalanta Baglioni the moment she held the body of her own dying son on the streets of Perugia half a decade earlier. The striking young man at the centre of the composition struggling with Christ’s legs is probably even an idealised portrait of Grifonetto himself.

The painting was immediately hailed as a stone-cold masterpiece, and remained one of the most prized works in all of Italy when the avaricious and unscrupulous Cardinal Scipione Borghese had a gang of heavies strip the painting from its altar in 1608 and hauled back to his Roman Villa, where you can still see it to this day in the magnificent Borghese Gallery.

3. Portrait of Andrea Navagero and Agostino Beazzano, Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, 1516

In addition to his talents as a painter of epic historical frescoes, pious altarpieces and riotous scenes from ancient mythology, Raphael was also one of the greatest portraitists to have ever picked up a brush. His extraordinarily realistic depictions of popes and cardinals, poets and diplomats are probing psychological analyses that still bring their distant sitters vividly to life 500 years later.

One of the finest is the remarkable double portrait of Agostino Beazzano and Andrea Navagero now housed in Rome’s Palazzo Doria Pamphilj. The fashionably attired sitters were both Venetian men of letters and diplomats who had come to Rome in 1516, and Raphael’s painting captures them looking up from their learned chitchat to stare us directly in the eye.

The portrait was intended as a gift for the renowned humanist Pietro Bembo, who could thus virtually take part in the discussion with his magnificently portrayed friends, each pulsing with individualism.

4. La Fornarina, Palazzo Barberini, c. 1518-19

Here’s to the baker’s daughter. Raphael’s startlingly realistic portraiture wasn’t just limited to the rarefied circles of powerful men. The startlingly intimate portrait known as La Fornarina now hanging in Rome’s Palazzo Barberini shows a dramatically different side of the painter.

A young woman wearing an exotic headdress stares frankly out at us as she ineffectually covers her bare breasts with a transparent veil, whilst a bracelet on her left arm bears Raphael’s own signature. The intimacy of the portrait is just about unlike anything else in Raphael’s oeuvre, and for good reason – the sitter is widely thought to be Margarita Luti, the daughter of a local baker and Raphael’s lover at the time of his death in 1520.

Some contemporary sources salaciously suggested that Raphael’s untimely demise was brought on by a particularly over-eager lovemaking session with Margarita, and it has even been suggested that the two had been secretly married on the basis of the ring the sitter wears on her finger. Whatever the truth, the ambiguous Fornarina is one of the great portraits of Renaissance art, and a fascinating insight into the private world of Raphael.

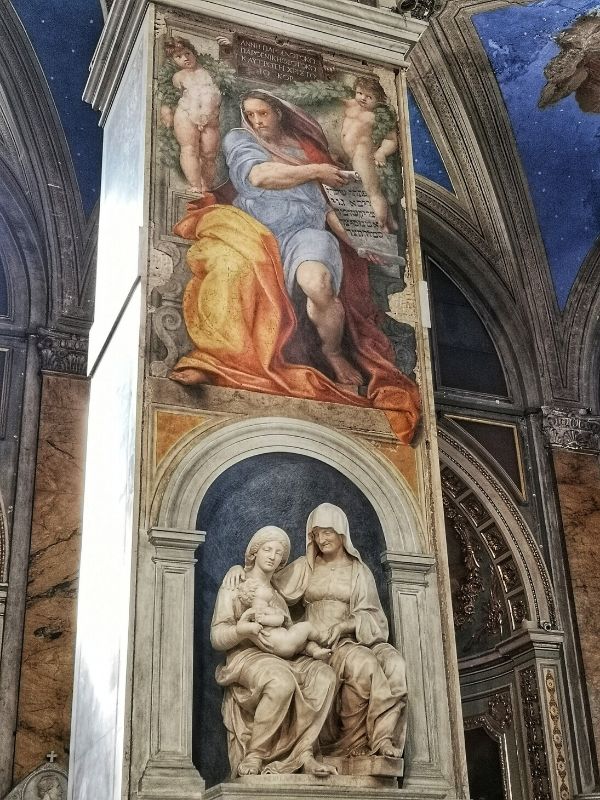

5. Isaiah, Sant’Agostino, 1513

Whilst he was working on the Vatican frescoes, the amazingly industrious Raphael also found time to paint a fresco depicting the prophet Isaiah for the altar of the learned German Augustinian monk Johann Goritz in the church of Sant’Agostino, across the road from Piazza Navona. Andrea Sansovino had already provided a beautiful sculpture of St. Anne, the Virgin Mary and the Infant Christ for Goritz’s altar, and Raphael’s thundering prophet was a worthy addition to the ensemble.

Isaiah is an awe-inspiring figure, obviously influenced by the monumental style pioneered by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. Twisting powerfully as taut muscles and sinews stretch and strain beneath his garments, the prophet’s exposed left leg has given rise to one of the great quips in the history of art. According to legend, Goritz complained to Michelangelo of the high price Raphael charged for the fresco, to which the great master irritably replied: ‘ the knee alone is worth the price.’

6. The Villa Farnesina, 1514-18

What happens when the vast wealth of the Pope’s personal banker joins forces with the talents of the greatest painter of the Italian Renaissance? The spectacular answer is the Villa Farnesina, a sumptuous pleasure palace built on the banks of the river Tiber for the fabulously wealthy Agostino Chigi, financier to the popes, at the start of the 16th century. Blessed with a limitless supply of ready cash, Chigi spared no expense in realising his vision of a relaxing country retreat on the very doorstep of the city, a ‘suburban villa’ from where he could effectively run his business empire and throw lavish parties that epitomised the bella figura of a golden age.

Chigi engaged Raphael to provide the interior decorations, and the fresco of Galatea provided by the artist for the entrance hall is one of his most enduring creations. Raphael’s first foray into the world of classical mythology, the story of Galatea comes from Homer’s Odyssey. In it, the blundering one-eyed Cyclops Polyphemus falls hopelessly in love with the flighty nymph Galatea, who predictably rejects the clumsy paeans of amor he plays her on his panpipes. Galatea leaves the lovelorn and furious monster far behind as she flees over the waves in a shell powered along by a troupe of dolphins, as putti and sea gods herald her journey.

As stunning as the Galatea fresco is, the Raphael-designed Loggia of Psyche leading out into the Villa’s garden might be even more spectacular. Depicting the love story of Cupid and Psyche from Apuleius’ Golden Ass, the elaborate fresco cycle weaves through illusionistic pergolas of fruits and flowers as it traces the fortunes of the star-crossed lovers that ultimately lead to their being welcomed into the ranks of the Gods.

Raphael and his assistants decorated the loggia when Chigi was finally preparing to marry his mistress Francesca Ordeaschi, and the magnificent scene of the celestial wedding banquet of Cupid and Psyche is a brilliant foreshadowing of the upcoming nuptials – one of the most important social events in 16th-century Rome attended even by the Pope himself.

7. Chigi Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo, 1516

The sumptuous Villa Farnesina wasn’t the only commission entrusted to Raphael by the fabulously wealthy Chigi. If the riverside mansion was a magnificent expression of Chigi’s lust for life and terrestrial verve, then the brooding mortuary chapel that he had Raphael design for him in the beautiful church of Santa Maria del Popolo is testament to the banker’s concern for his eternal soul. This time Raphael wasn’t just responsible for the decorations – the painter had become architect.

Where the Villa Farnesina is light, airy and full of the joys of love, the Chigi chapel is dark and sombre, weighed down with the spectre of death. The innovatively designed mausoleum is surmounted by a miniature version of the Pantheon’s dome - in place of the oculus at its centre, here a mosaic of God the Father sets the world in motion. The tomb of Chigi himself takes the form of a flattened pyramid of marble – traditional symbol of eternity. To Raphael we also owe the design of the sculpture of Jonas, although the chapel’s most impressive statues – those of Daniel and Habbakuk - were added by Baroque master Bernini over a century later, who completed the chapel.

When Chigi died in April 1520, he was interred here amongst the incredible variety of coloured marbles and mosaics, of masterful sculptures and beautiful frescoes - the Chigi Chapel is one of the great masterpieces of Raphael’s imagination. Incredibly, the painter himself had died just five days before his most illustrious patron.

8. Sibyls, Chigi Chapel, Santa Maria della Pace, 1514

Continuing the dynamic partnership between the most in-demand painter of the Renaissance and the 16th-century’s richest man, Chigi also employed Raphael to fresco the family chapel in Santa Maria della Pace in 1514. The pint-sized church itself is tucked away in one of the historic centre’s most charming piazzas, and is notable for Pietro da Cortona’s elegantly curving Baroque façade as well as Bramante’s stunning Renaissance cloister. Inside, what the church lacks in size it more than makes up for in artistic heritage, boasting works from the likes of Baldassare Peruzzi, Orazio Gentileschi, Antonio da Sangallo and, most impressively, Raphael himself.

On the outer wall of the Chigi chapel, the first on the right as you enter the church, Raphael painted the ancient Sibyls - Greek mythological seers who according to Christian thought predicted the coming of Christ to the pagans of antiquity. The four sibyls (the Cumaean, the Persian, the Phrygian, and the Tiburtine) surround the chapel’s upper entrance arch, studiously taking down prophecies dictated to them by angels swooping from heaven above.

The Sibyls had been immortalised in the story of art with the unveiling of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling just two years earlier, and the long shadow of Michelangelo is apparent in Raphael’s work. The more harmonious Raphael has however tempered the exaggerated musculature of Michelangelo’s monumental prototypes, painting the Sibyls as young women in billowing garments - powerful and yet still imbued with the artist’s ever-present sense of grace and beauty as they float charmingly above the Chigi chapel.

Tip: climb up to the upper floor of Bramante’s adjacent cloister to find one of the city’s most evocative aperitivo bars at the top. Make your way into a side room and be rewarded with a great view of Raphael’s frescoes from a window looking down into the interior of the church.

9. The Transfiguration, Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican Museums

‘Christ was transfigured before them, and his face did shine as the sun, and his raiment was white as light.’

The last work Raphael was destined to paint in his illustrious but tragically short career is considered by many to be his finest. Commissioned by Giulio de’Medici – the future Pope Clement VII - the massive altarpiece was intended to adorn the cathedral of Narbonne in France, where Giulio was archbishop.

The subject matter is a rather ambiguous moment in the New Testament where Jesus has gone with his disciples to pray on a mountainside. The Messiah is suddenly surrounded by a halo of blinding white light and levitates heavenward along with the apparitions of Moses and Elijah, as a voice from the sky greets him as the son of God. In order to depict this fundamentally abstract miracle, Raphael resorts to a virtuoso harnessing of the power of light – we can almost feel the blinding celestial rays that light up the mountain top, knocking over Peter, James and John with their superhuman force.

Raphael in fact combines the events of the Transfiguration with the subsequent Gospel narrative, when Christ’s apostles struggle in vain to cure a young boy possessed by demons – the boy would have to wait for Jesus’ return from the mountain to be successfully exorcised. A masterpiece both of composition and colouring, the contrast between the celestial world of divine revelation, suffused with blinding white light, and that of the terrestrial world where extraordinarily realistic figures gesture from the miracle of Christ’s Transfiguration to that of the exorcised boy, shows Raphael as the master of both artistic registers.

When the raging fever that carried Raphael to his grave struck the painter, the Transfiguration was all but finished. According to legend it stood at the foot of his deathbed as Raphael’s condition worsened, silent last will and testament to the man that would be hailed as the “God of Art” on his demise.