Rome was the largest and greatest city of the ancient world, and a roll-call of its most famous classical monuments today immediately conjure up splendid visions of a glorious antique past: who could imagine visiting the Eternal City without following in the footsteps of the gladiators at the awe-inspiring Colosseum, or exploring the ancient imperial palaces on the Palatine Hill? No trip to Rome would be complete without immersing yourself in the daily life of antiquity in the Forum, meanwhile, or standing in the centre of the yawning Circus Maximus, where daredevil chariot races were cheered on by crowds of over 300,000 spectators.

But in Rome, these world-famous landmarks really are just the beginning. Traces of the ancient world are everywhere you look here. Indeed, it’s difficult to walk more than a few paces without coming across some new ruin, whether it’s an ancient temple dedicated to some obscure pagan god, a gateway into the city or a fabulously decorated antique sepulchre. Coming across these lesser-known ancient remains is one of the great pleasures of visiting the Eternal city, and it’s why you’d need a lifetime or more to uncover all the surprises Rome has to offer. This week on our blog we’re counting down 11 of our favourite off-the-beaten-track ancient monuments in the city. How many have you seen?

Ancient Rome Tours

Visit Ostia Antica

Just inside the Aurelian walls, picturesquely hemmed in by the tram tracks on one side and the train tracks on the other, lies the beautiful but erroneously named temple of Minerva Medica – for centuries thought to be a sacred space dedicated to the goddess Minerva in her guise of doctor. Named for a statue of Minerva holding a snake that was erroneously thought to have been found on the site in the 16th century, this imposing 12-sided brick building featured a covered domed hall punctured by semi-circular niches and windows. Amazingly, the 25-metre diameter dome was the third largest in the ancient city after the Pantheon and the Baths of Caracalla.

In reality, it seems that the edifice had nothing whatever to do with Minerva, and probably wasn’t even a temple at all; instead, latest scholarship suggests that the the building was a nymphaeum in the Horti Linciani complex, a lavish 3rd century villa featuring landscaped gardens that was built under the emperor Licinius Gallienus. Hardly anything is actually known about the building, but it is has for centuries been admired as one of the most impressive and best-surviving examples of late-imperial Roman architecture in the city – such is it’s picturesque character that artists from Piranesi to JWM Turner have immortalised it with their pens. Whatever its original function, it’s one of the city’s most impressive and under-visited ancient monuments.

The mad, bad and egomaniacal Nero is one of history’s most notorious characters, his tyrannical reign the stuff of legend. But the emperor certainly knew how to live in style. His vast palace – known as the Domus Aurea because its every surface glittered with gold – was ancient Rome’s most spectacular building, and scarcely believable highlights included a rotating dining room open to the starry night sky and a massive artificial lake.

The centrepiece of Nero’s Golden House was a massive artificial lake ringed by columns, before which stood a colossal 120 foot tall statue of the emperor himself. But the good times didn’t last long, and when the egomaniacal Nero was finally deposed his successor Vespasian unsurprisingly sought to make a clean break from his wicked predecessor. And so mere decades after its construction, Nero’s immense party pad was pulled down and its lake drained and filled in. On the site of the private lake that so vividly symbolised the contempt Nero held for the city’s populace, Vespasian erected a public arena as a gift to the people, known as the Flavian amphitheatre. It is more than a little ironic, then, that in the 11th century the abandoned structure started being referred to as the Colosseum in reference to the colossal statue of Nero that once stood there.

And the Domus Aurea itself? Magnificent remains lay buried and forgotten underground for centuries, until it was rediscovered during the Renaissance as part of a wider craze for antiquarianism and the revival of the city’s ancient splendours. Artists were amazed at the beauty of the decorations that still decorated the long-forgotten halls underground, and the building was to have a huge impact on the development of aesthetic ideals during the Renaissance.

Today you can walk the halls of the Domus Aurea and see this incredible space for yourself on a special guided tour – one of the most exciting off-the-beaten-path experiences in Rome!

“Will anybody compare the idle Pyramids, or those other useless though renowned works of the Greeks with these aqueducts, with these many indispensable structures?”

So said Frontinus, Rome’s water commissioner in the 1st-century AD, justifiably proud of the incredible aqueducts which still stand as majestic icons of ancient ingenuity even today. To see the achievements of the ancient Roman engineers at their best, head to Rome’s beautiful Parco degli Acquedotti, where the extensive remains of the massive Acqua Claudia meander picturesquely through umbrella pines and wildflower meadows.

One of the four great aqueducts of ancient Rome, the Aqua Claudia was begun by Caligula in 38AD and completed by his successor Claudiu, bringing fresh water into the ancient city and making its massive population growth possible. Travelling 69 kilometres across the Lazio countryside, the aqueduct brought 190,000 cubic metres of water to Rome every 24 hours. Playing to character, Nero diverted the water into a new aqueduct that brought the endless supply of water required for his artificial lakes and fountains in his opulent Golden House, or Dumus Aurea.

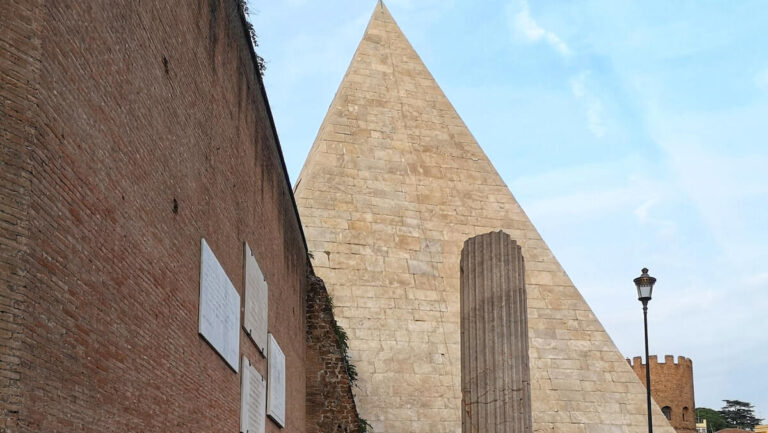

Staking a strong claim for ancient Rome’s most unexpected monument is this pristine pyramid hiding in plain sight in the bustling Ostiense quarter, just across the road from one of the city’s busiest train stations. After Egypt was conquered by the Roman legions in the final decades of the first century BC, a craze for all things Egyptian swept the capital of the ancient Empire, from temples to exotic gods and massive obelisks, which you can still see marking important piazzas and crossroads across Rome.

Perhaps the most ostentatious example is this, the magnificently preserved funeral monument of one Caius Cestius built between 18 and 12 BC. Cestius held the important political offices of praetor and tribune during his lifetime, and resolved to immortalise himself with this 36-metre-high pyramid made from massive slabs of Lunense marble and decorated with frescoes inside.

No it’s not the Colosseum, but a too-hasty glance at Rome’s Teatro Marcello has deceived many first-time visitors to the Eternal City. The ancient Roman theatre does somewhat resemble a mini Colosseum, but the events that took place here were of an altogether less bloody nature – plays and music recitals being the order of the day. The nearly 20,000 capacity venue was begun by Julius Caesar and completed around 13 BC by the Emperor Augustus, who named it after his favourite nephew and presumptive heir Marcellus – whose untimely death at age 19 left the emperor grief-struck.

Thanks to its strategic location near the river, after the fall of the Roman Empire the edifice was transformed into a fortress by the Pierleoni family; a Renaissance palace was built atop the remains in the 16th century to designs by renowned architect Baldassare Peruzzi, which you can still see surmounting the ancient arcades today.

One of Rome’s most important – and surprisingly little-visited – archaeological complexes, the tombs of the Via Latina comprise a series of beautifully preserved antique sepulchres lining a stretch of an ancient Roman road hidden away in plain sight in a southern Roman suburb. Many of the tombs date from as far back as the 1st century AD, including the Barberini or Corneli tomb, a split-level affair that includes an underground hypogeum surmounted by a richly decorated vaulted upper story featuring winged victories, marine animals and various fantastic creatures. No less impressive are the Pancrazi tomb, also decorated with vibrant frescoes, polychrome stuccoes and mosaic floors, and the Valerii tomb, complete with 35 medallions featuring Dionysian scenes.

In any other city in the world this archaeological park would be considered a must-visit highlight, but such is the nature of Rome that hardly anyone comes here. Get there by taking the A line of the metro as far as Arco di Travertino – from there it’s an easy 5-10 minute walk. Entrance is free.

The magnificent and massive Baths of Diocletian was the largest public baths complex in ancient Rome, built between 298 and 306 AD on the orders of the emperor Maximian in honour of his co-emperor Dicoletian. The baths could hold 3,000 people at one time and took up an incredible 120,000 square metres, spreading across the valley between the Viminal and Quirinal hills.

Baths were fundamental to Roman life, where bathing was a daily activity vital for both health and socialising. Even thugh only a small part remains intact today, they give a vivid sense of how awe-inspiring the original complex must have been. The main rooms were aligned on a central axis. First came the caldarium, where a pool was kept at scalding temperatures by an elaborate system of air ducts and pipes; the caldarium led to the tepidarium, where the temperature was less extreme; bathers would finish their spa routine by plunging into the icy waters of the frigidarium. Others features of the complex included a massive open-air swimming pool known as the natatio, as well as a series of gyms.

Today part of the baths are visitable once again as part of Rome’s National Museum (another part was transformed into a church by Michelangelo). The Baths are hidden away just across the road from Termini station, an oasis of calm that takes you back in time to the splendours of the ancient world just moments from the modern traffic.

Built way back in the second century BC, the imposing Portico d’Ottavia is one of the most recognisable landmarks in Rome’s Jewish quarter. The spectacular colonnaded portico is named after Octavia, the sister of the Roman emperor Augustus who reconstructed the monument during his reign. In antiquity the Portico d’Ottavia was studded with magnificent bronze equestrian statues, but after the fall of the Roman empire the portico took on an altogether humbler role in the life of the city, becoming the site of medieval Rome’s fish market.

Look closely and you’ll see a record of the now defunct fish-market in a Latin sign on the right hand side of the monument, mandating that ‘the heads of any fish that measure longer than this slab must be handed over to the conservatori’ (powerful city administrators) – the heads were considered delicacies perfect for making fish soup, and the city hall fat cats made sure they got their share.

One of the few Roman streets that appears today almost exactly as it did in antiquity, the Clivus Scauri formed part of the route that led from the Circus Maximus to the Colosseum. The road is recorded in written sources from as far back as the 6th century, and was created under the auspices of a prominent member of the well-to-do Aemilii Scauri family – probably Marco Emilio Scauro, censor in 109 BC. The Clivus Scauri is still flanked by residential buildings from ancient Rome (which you can visit) and the remains of the ancient temple of the Divine Claudius. The arches that surmount the road and support the buildings on either side were built between the 3rd century AD and the Middle Ages.

Located just a few steps from the Mouth of Truth, the arch of Janus is the only quadrifrons arch surviving from ancient Rome. A quadrifrons arch features four facades rather than two, which means it faces in every direction. The name of the arch derives from Janus, a many-faced god in the ancient Roman pantheon who presided over beginnings and transitions. The squat arch is punctured by 48 niches designed to carry statues of ancient gods, and occupied an important position at the edge of the Forum Boarium, ancient Rome’s bustling cattle market.

The largest park in ancient Rome, the Horti Sallustiani were owned by the historian Sallust, who purchased them from the estate of Julius Caesar after the latter’s assassination in 44 BC. The nature-loving historian transformed the property into a beautiful series of landscaped gardens, orchards and groves, a paradisiacal retreat from the chaos and squalor of the ancient metropolis where he could pursue his studies in splendid isolation.

The urban oasis proved popular with the creme-de-la-creme of Roman society, and after Sallust’s death the site passed into the hands of a series of emperors, who expanded and elaborated the historian’s property. With the rapid modern expansion of the city in the late 19th century most traces of the ancient gardens were erased, with the exception of these ruins that can be seen in Piazza Sallustio, fully 14 metres below the current street level.

We hope you enjoyed our guide to some of ancient Rome’s most fascinating hidden sites! Through Eternity Tours offer expert-led group and private itineraries to all of Rome’s major archaeological sites, including exclusive visits to the Colosseum. If you’d like to visit any of the sites mentioned in this list with one of our resident archaeologists, get in touch with our team of travel experts today and we’d be delighted to plan your perfect itinerary!

Book Your Ancient Rome Experience