The blood of San Gennaro is examined in Naples cathedral (credit - Paola Magni, CC BY 2.0)

The blood of San Gennaro is examined in Naples cathedral (credit - Paola Magni, CC BY 2.0)

Naples can rest easy tonight, for its saint still bleeds. Writing about any other city, such a sentence would no doubt seem strange. But Naples isn’t just any other city. This is a place where tangled secrets, legends and religious cult maintain a powerful grip on the population, guiding the rhythms of its social life with unwavering regularity. It is a mysterious place, dark and fascinating, that can be difficult for outsiders to fully understand. It’s a city of skulls and bleeding statues, of black humour and high art.

But amidst this confusing landscape, in this world of processions and rituals, one sacred rite stands above all others in importance. Three times a year, on the first Saturday in May (recalling the translation of the saint’s relics from Pozzuoli to Naples), the 19th of September (in honour of his feast day), and the 16th of December (commemorating an event in 1631 when an intervention from beyond the grave miraculously stilled a devastating eruption of Mount Vesuvius), the preserved blood of Naples’ patron saint Gennaro miraculously liquefies before a faithful and ecstatic crowd in the city’s great cathedral.

Louis Finson, San Gennaro with his head and ampoules of blood, 1610

Louis Finson, San Gennaro with his head and ampoules of blood, 1610

San Gennaro (or Januarius in his English-language iteration) might be at the top of Naples’ jam-packed saintly pantheon, but he remains something of an obscure figure. No contemporary accounts of his life survive, but according to later sources Gennaro hailed from the city of Benevento to the east of Naples, where he rose to the rank of archbishop. Unlucky enough to be alive during the reign of the criminally insane and excessively anti-Christian emperor Diocletian, Gennaro apparently lost his head during a purge sometime in the early 4th century after being caught in the act of preaching to the Christian faithful in Pozzuoli.

The Catacombs of San Gennaro, where the saint's body was housed until the 9th century

The Catacombs of San Gennaro, where the saint's body was housed until the 9th century

Amidst the throes of her grief, a pious local woman by the name of Eusebia had the presence of mind to collect some blood from the saint’s freshly dismembered corpse, depositing it in two ampoules which she carried with her everywhere she went. When the bishop Severus transported Gennaro’s relics from the place in which they were secretly interred to the Neapolitan catacombs some decades later, he encountered Eusebia en-route; in the presence of the saint’s decapitated head, the by-now long dried blood in the ampoules spontaneously liquefied - and so the legendary miracle was born. The importance of the miracle to the people has grown ever since, culminating in the huge spectacle that we see today.

The Chapel of San Gennaro, Naples Cathedral

The Chapel of San Gennaro, Naples Cathedral

The debates have long raged between the faithful, who are convinced that the miracle is a direct sign from an omniscient higher-power, and those who believe it to be either a hoax or a natural phenomenon. Far more interesting, however, is what the whole institution of this curious ritual tells us about this eccentric city and her people. Gennaro is not the only Neapolitan saint whose blood continues to outlive his body. A vial of Santa Patrizia’s dried blood apparently liquefies every Tuesday morning in the monastery of San Gregorio Armeno, and the sanguineous remains of Saints Pantaleone and Stephen occasionally get in on the act as well. Not for nothing is Naples known as Urbs Sanguinum – Neapolitans, it seems, are obsessed with blood.

This is a liquid so precious that it verges on the miraculous even when it is not mysteriously changing state. It is the substance that links the living to the dead, and symbolises both in equal measure. For a society fascinated by the twin poles of this powerful dichotomy and the liminal world between them, its symbolic power is obvious. From the ritual cleansing of decaying corpses to the once widespread practice of skull worship, many of the city’s most curious customs, macabre rituals bordering on the fetishistic in the eyes of many, are really attempts to negotiate this purgatorial borderland.

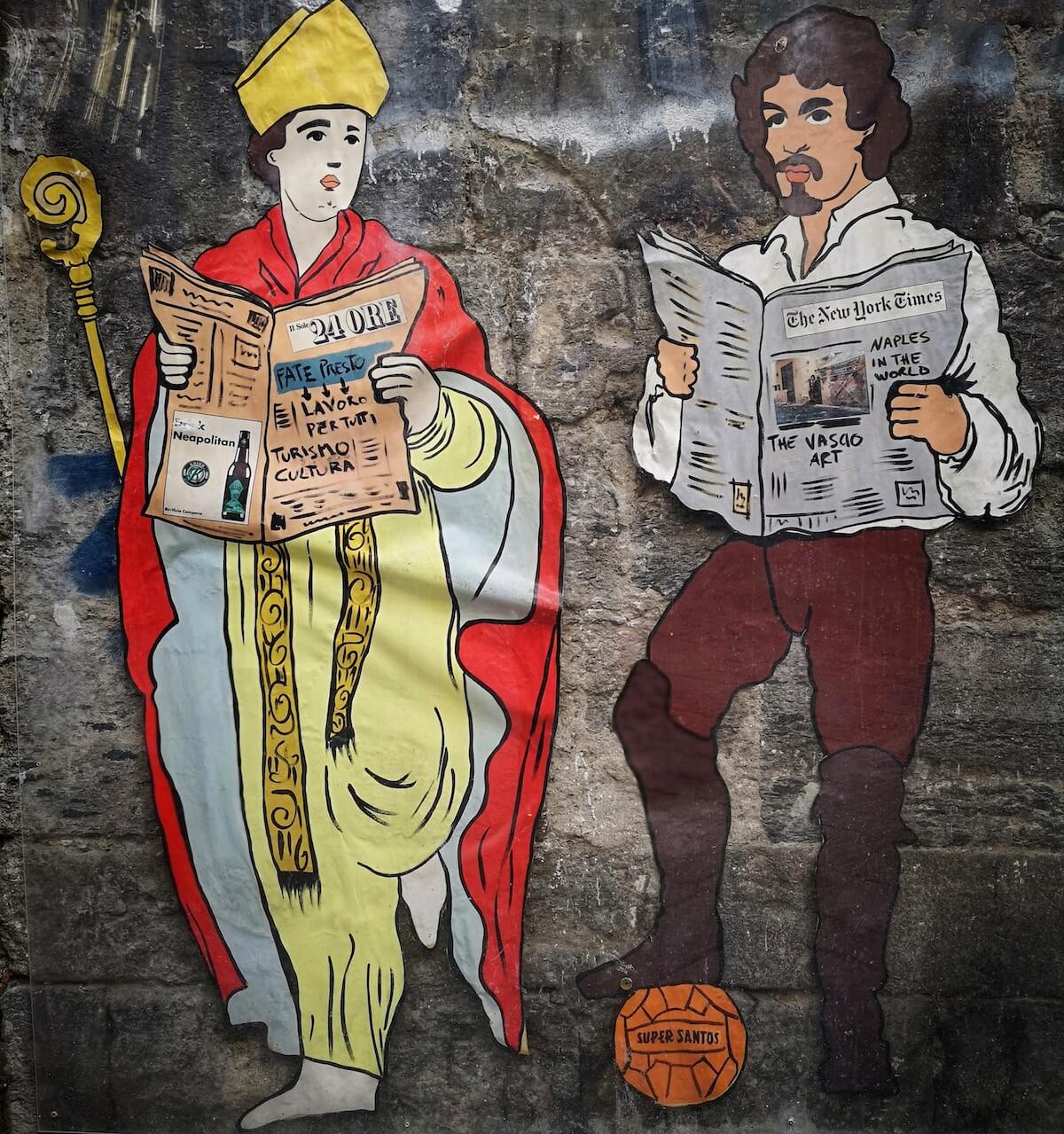

San Gennaro and Caravaggio hanging out in a Neapolitan mural by street artist Roxy in the Box.

San Gennaro and Caravaggio hanging out in a Neapolitan mural by street artist Roxy in the Box.

To get a sense of just how much the miracle of San Gennaro means to the people of Naples, you really need to attend the events in the cathedral for yourself. Push your way into the crowd and you’ll be surrounded by people of every age and background imploring, cajoling, and demanding that Gennaro do his civic duty by consenting for his blood to liquefy and thus protect the city. “Fai presto San Genna, fai presto!” (do it quickly Gennaro, quickly!) yells one; “Gennaro ci ama, Gennaro ci vuole bene!” (Gennaro loves us, he wants the best for us!) intones another. And Neapolitans haven’t been above offering bribes to their patron saint in order to ensure his continuing benefaction: historical records show that Gennaro has been in receipt of a slew of ex-voto offerings over the centuries, from wax statuettes to precious simulacra in silver and gold.

Skull decoration outside the church of Purgatorio ad Arco, Naples

Skull decoration outside the church of Purgatorio ad Arco, Naples

This near obsessive preoccupation with the successful realisation of the miracle is well founded. The miracle of San Gennaro proposes nothing less than a Christian triumph over death, a visceral reminder that Gennaro continues to look benevolently over the people of Naples. For as their patron saint he is an intercessor with the divine, a direct line to God operating on their behalf. The failure of his miracle means the link between the terrestrial world of Naples and the celestial world above, symbolised in the still flowing blood of San Gennaro, has been severed - and terrible events are in store for the city. The city lies unprotected, exposed to the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.

Whilst their ancient forebears might have augured the future in the entrails of some unfortunate animal or in the flight of the birds wheeling overhead, it is the blood of San Gennaro that today acts as a divining rod for Neapolitan fortunes. In 1980, the miracle’s non-event presaged a horrific earthquake in nearby Irpinia, where 3,000 people died. Vesuvius’s last eruption in 1944 predictably followed a non-liquefaction, whilst the blood also failed to liquify in 2020, at the height of the Covid pandemic. Perhaps most seriously of all in calcio obsessed Naples, a failure of the blood in 1988 preceded a disastrous football loss to Milan that sent the entire city into mourning.

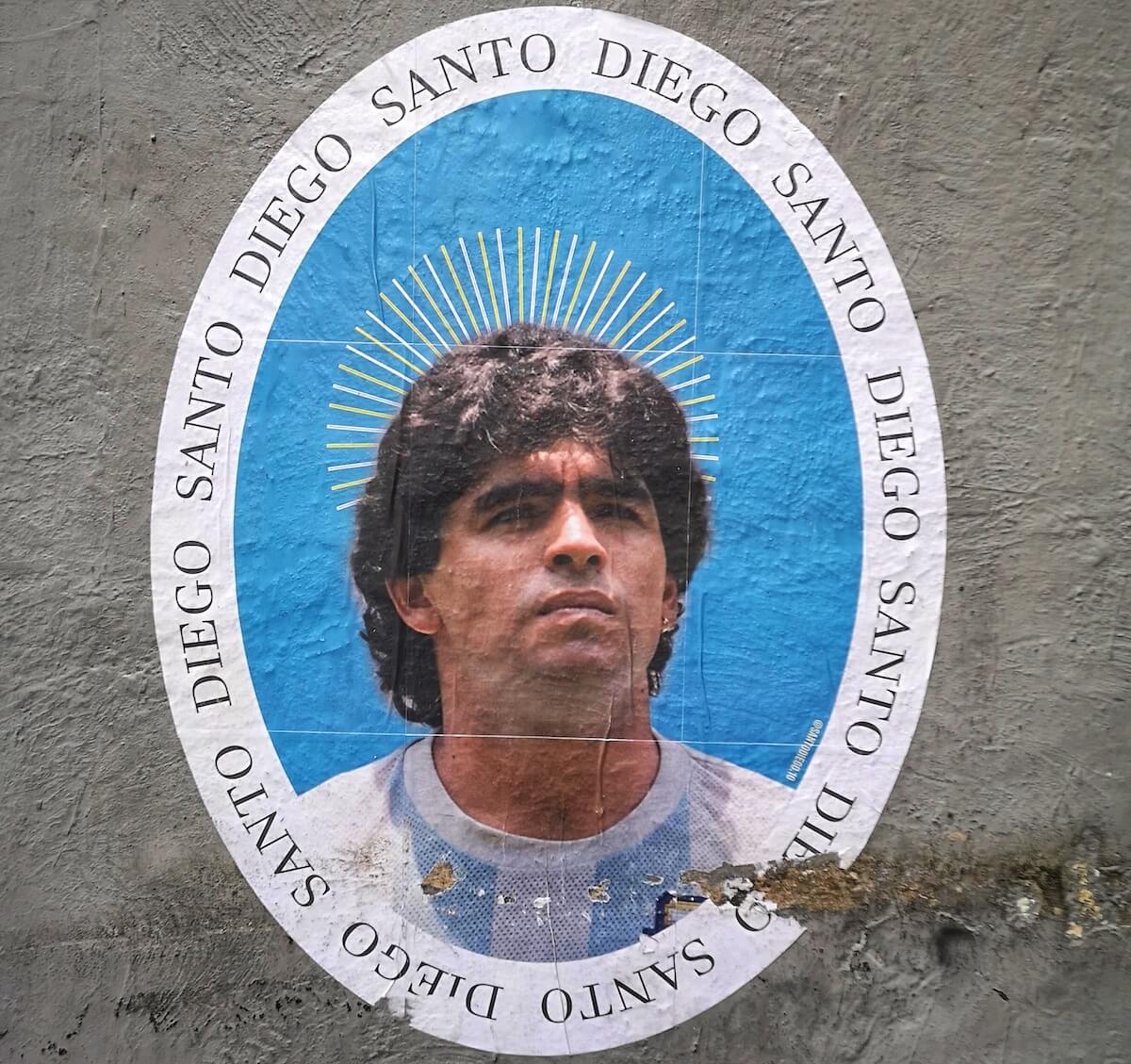

Sticker dedicated to "Saint Diego", Naples

Sticker dedicated to "Saint Diego", Naples

When Naples ended 60 years of heartbreak by winning the title the year before, by contrast, their unoffically (and sacrilegeously) sanctified hero Diego Maradona was depicted in the embrace of none other than San Gennaro (whose blood had obligingly liquefied that year) on walls all over the city. This year, incidentally, Naples head into the Christmas break with an unprecedented eight point lead over their nearest rivals for the Scudetto, with the team in pole position to end another painful drought. Locals are praying that Gennaro and the sadly departed Diego are smiling down from them on high. And the indications drawn from the sacred blood, for the next five months at least, are positive.

A massive mural of San Gennaro by street artist Jorit Agoch greets passersby in the Forcella district

A massive mural of San Gennaro by street artist Jorit Agoch greets passersby in the Forcella district

When the archbishop of Naples opened the safe that contains the famous receptacle at 9am, San Gennaro’s ancient blood remained stubbornly solid. But not to worry - the miracle is known to take some time in its winter installment, perhaps due to the harsher environmental conditions. After an anxious wait of nearly two hours in the spectacular Chapel of San Gennaro, the good news finally came through at 10.56 when the cardinal announced that the miracle had taken place, to cheers and sighs of relief. Naples can rest easy tonight, for the watchman is at his post. Life-blood continues to flow through the veins and arteries of the city.

Evviva San Gennaro!