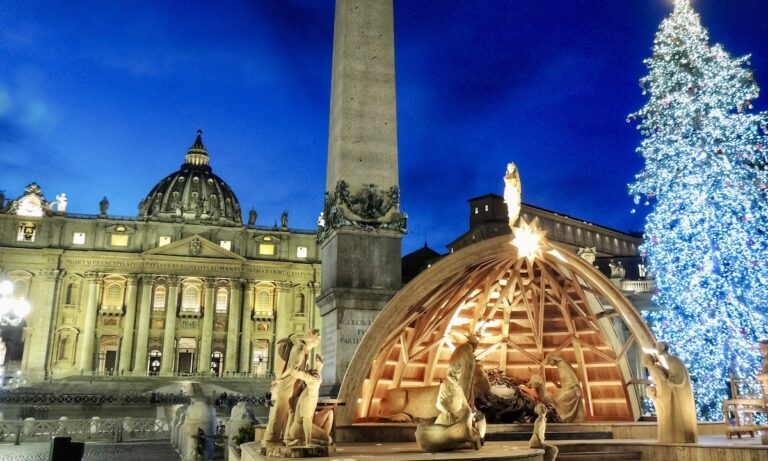

It’s mid-December in Rome, and the charming cobbled streets of the city’s historic center are swarming with shoppers on the hunt for the perfect gift. Via del Corso is bright with Christmas lights, while Piazza del Popolo and Saint Peter’s Square are dominated by gigantic Christmas trees brought down from distant Alpine forests. A buzzing Christmas market on Piazza Navona brims with festive cheer, whilst gorgeous Nativity scenes grace Rome’s most beautiful churches. Yes, the festive season is a truly wonderful time of the year to visit the Eternal City!

But the holiday merriment that characterizes the dying days of the year has a much longer history here than you might think. Before tinsel and fairy lights, before yuletide carols and advent calendars, before, indeed, the birth of Christ in a faraway Bethlehem stable, there was Saturnalia.

Rome Religious Tours

Visit the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore

Described by the Roman poet Catullus aso optimo dierum, or ‘the best of all days,’ this Roman festival began life as a one-day festival celebrated on the 17th of December to honor Saturn, the ancient god of agriculture and the harvest. Over time the celebration took on a life of its own, eventually becoming a wild week-long party from the 17th to the 23rd of December. Saturn was believed to have ruled over a Golden Age in the distant past, a simpler and more peaceful time, and Saturnalia was celebrated in this spirit.

Saturnalia began with a sacrifice of pigs in front of the Temple of Saturn in the Roman Forum. Like all pagan temples in Ancient Rome, the interior of the temple was inaccessible to the general public, so ordinary Romans would not have been able to see the remarkable hollow statue of Saturn inside, which was filled with olive oil. Unlike the Christian churches of Rome – which are open to everyone – the secrets of the ancient Roman temples remained behind closed doors.

In December, however, the Temple of Saturn became a symbol of revelry and role reversal that heralded the temporary postponement of the strict hierarchies that usually defined the social world of ancient Roman civilization. Romans who gathered on the temple steps may not have been permitted to enter, but they could witness the sacrifice that heralded the beginning of an extraordinary period of festivities, and take part in a public banquet of the slaughtered pigs the following day.

After the sacrifice, public rituals included a lectisternium, where an image of Saturn was placed on a couch and offered food, as well as the much-anticipated public banquet. At home Romans bathed early and sacrificed a suckling pig in honour of the god. Some aspects of the holiday, like the closure of schools, resemble modern holidays, while others were more unconventional.

In a brilliant passage, the ancient satirist Lucian imagines Saturn himself describing the prevailing atmosphere of Saturnalia:

During my week, the serious is barred; no business allowed. Drinking and being drunk, noise and games and dice, the appointing of kings and the feasting of slaves, singing naked, clapping of tremulous hands, an occasional ducking of corked faces in icy water – such are the functions over which I preside.

Indeed, part of the fun of Saturnalia was that social norms and hierarchies were temporarily turned upside down; most famously, slaves feasted like their masters and were allowed to dine first in their households, waited on by their owners. The author Macrobius tells us how families “first of all honour the slaves with a dinner prepared as if for the master; and only afterwards is the table set again for the head of the household.” Slaves could also speak freely without fear of punishment and wear clothing that was usually the preserve of free citizens.

Unsurprisingly, Saturnalia was one of the most popular Roman holidays. Citizens and slaves alike revelled in the opportunity to run wild, speaking, dressing, drinking and gambling – a practice usually strictly forbidden but actively encouraged during the seven days of Saturnalia – without restraint.

People may have worn masks, like in modern day carnival celebrations, while gifts were exchanged on the 23rd of December in a ritual known as the Sigillaria – perhaps the strongest echo of our own Christmas customs. The most popular gifts for this occasion were little figurines of gods made out of clay, which were then put on display on domestic altars: some scholars see the origin of the Italian tradition of the Nativity crib in this practice. The poet Martial provides a long list of other gifts that might be appropriate, including modern stocking filler classics like quill pins, pipes, decorative hairpins, drinking flasks and even slippers!

Yet not everyone embraced the hedonistic spirit of Saturnalia. The ever-studious Pliny the Younger retreated to some quiet rooms in his villa outside of Rome when the chaos of the festivities became too much: “This way I don’t hamper the games of my people and they don’t hinder my work or studies.” Seneca, meanwhile – never exactly a barrel of laughs even at the best of times – observed disapprovingly in a letter to his confidante Lucilius that “the whole mob has let itself go in pleasures,” vomiting in the streets and generally carrying on in a matter wholly unbefitting of Roman dignity.

These days of hedonistic pleasures and excess were inevitably viewed as a convenient distraction by those with dark intentions. The Catiline conspiracy, which involved plans to commit arson and murder senators in an attempt to overthrow the Roman Republic, was deliberately scheduled for Saturnalia. Catiline, the senator who led the conspiracy, must have hoped that the majority of Romans would be too drunk and distracted to notice that he was up to no good. Unfortunately for Catiline, Cicero remained alert even during the dissipation of Saturnalia. The plot was exposed, and Catiline was forced to flee Rome.

For most of us these days, the holiday period is a valuable opportunity to spend time with loved ones; but Roman emperors tended to be less sentimental about family time. In AD 211 Caracalla plotted the assassination of his younger brother Geta during Saturnalia, arranging a bogus “peace meeting” with his sibling rival which ended with Geta dying in his mother’s arms.

Yet for ordinary Romans who were not embroiled in politics and power play, Saturnalia was characterized above all as a cheerful and peaceful period of relative tolerance. Even the most outspoken slaves or debauched parties were not really considered a threat to society, as everyone in Rome knew that the fun would come to an end within a week, and everything would go back to normal.

The connection between Saturnalia and Christmas has always been a subject of dispute. There are some striking similarities; both festivals occurred at the same time of year and involved feasting and gift-giving. However, the differences are pretty striking too. Thankfully, there has never been a Christmas equivalent of the Saturnalia tradition where dead gladiators were given as offerings to Saturn!

It is now generally agreed that the festival of dies natalis solis invicti (“birthday of the unconquered sun”), which was celebrated on 25th December, is more closely connected with Christmas than Saturnalia itself. The celebration of Christmas as we know it – the commemoration of the birth of Christ on 25th December – really took off in the centuries after the Roman Empire largely converted to Christianity. The first official mention of a Christmas festival comes from the year 336 AD, although it was celebrated on the 6th of January instead. We have to wait until around the year 360 AD for the adoption of the date we know today.

Saturnalia, Sol Invictus, and other pagan beliefs and traditions were gradually forgotten over time and morphed into Christian celebrations. But as you walk through Rome, past churches and lavishly decorated shop windows, take a detour to the Roman Forum and the still stunning remains of the Temple of Saturn to reflect on another kind of festive spirit that existed in this city so many centuries ago!

Book Your Ancient Rome Experience