When the doctor and avid collector Sir Hans Sloane donated his massive collection of 71,000 artefacts to the British State in 1753, the world’s first public national museum was born. Originally sited in the palatial Montagu House, the collection was free and open to ‘all studious and curious persons’ from the outset. The collection quickly grew, and a massive new neo-classical building designed by Robert Smirke was constructed between 1825 and 1857 to house the museum. As the British Empire reached the peak of its power and extent, objects kept flooding in from across the globe, and today the museum is home to a staggering 8 million objects. From ancient Greece to Egypt, Mexico, Nigeria and beyond, whatever you’re interested in you’ll find it here. You could easily spend weeks or months in the sprawling collection without seeing everything, but if you’re looking for somewhere to start then check out our guide to 10 highlights of the British Museum below!

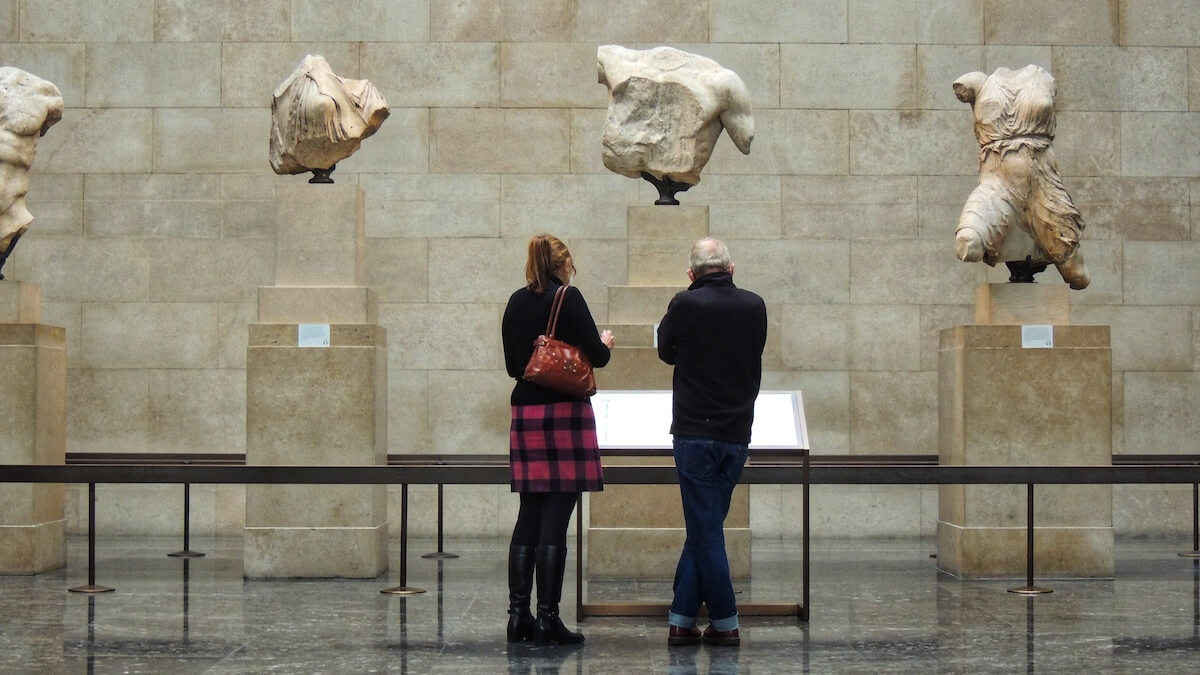

The Parthenon Marbles

Also known as the Elgin marbles, this collection of Greek sculptures taken from the Parthenon in Athens is possibly the most important grouping of classical sculpture in existence. The Parthenon is the centrepiece of the Athenian Acropolis, and was decorated with sculptures by the renowned ancient sculptor Phidias and his assistants between 443 and 437 BC. The majority of the sculptures in the British Museum come from the 160 metre-long frieze that ran around the building, and features scenes from ancient war and mythology. Comprising hundreds of human, animal and mythological figures, the highly naturalistic Parthenon marbles are widely considered the high-point of the High-Classical period of Greek sculpture. The Earl of Elgin, Thomas Bruce, removed a large proportion of the Parthenon frieze between 1801 and 1812 and had them carted back to Britain in a move whose legality has been questioned ever since. The marbles remain amongst the British Museum’s most controversial objects but are an absolute must-see for anyone interested in Classical art.

Where to find it: Room 18, Ground Floor, Level 0

The Nereid Monument

This monumental tomb was likely constructed on the orders of Erbinna, the ruler of Xanthos in present-day Turkey. Although Xanthos was part of the Lycian empire, the influence of Greek models of classical architecture and sculpture were widely adopted in its monuments, and Erbinna’s tomb strongly recalls the form of a Greek temple. The monument is named after the highly expressive sculptures that were located between the tomb’s columns, which depict the Nereids - sea nymphs that provided protection to sailors on the stormy high seas. Although the temple’s reconstruction at the British Museum is hypothetical and the location of the individual sculptures open to debate, the Nereid monument gives a vivid sense of the refined culture of the Lycians.

Where to find it: Room 17, Ground floor, Level 0

Coffin of Hornedjitef

Most visitors coming to the British Museum make a beeline for the Egyptian rooms, and for good reason. The museum’s display of mummies, sarcophagi and funerary objects from the ancient empire on the Nile are truly jaw-dropping, none more so than the coffin and mummy of the Egyptian high priest Hornedjitef, who was responsible for the Temple of Amun at Karnak in the Ptolemaic period. For ancient Egyptians like Hornedjitef, the mummification of the body was central to one’s chances of life after death. The delicately decorated inner case of the priest’s coffin is a masterful example of Egyptian art, and features a map of the celestial sphere to help him on his journey through the afterlife. It’s an eerie experience indeed to lock gazes with this powerful figure from across the centuries, his eye shining out from the golden features of his sculpted face. Also belonging to Hornedjitef’s funerary objects is a fascinating papyrus Book of the Dead, a collection of spells and invocations that were intended to aid the defunct priest’s difficult journey through the underworld and into the afterlife beyond.

Where to find it: Room 63, Upper Floors, Level 3

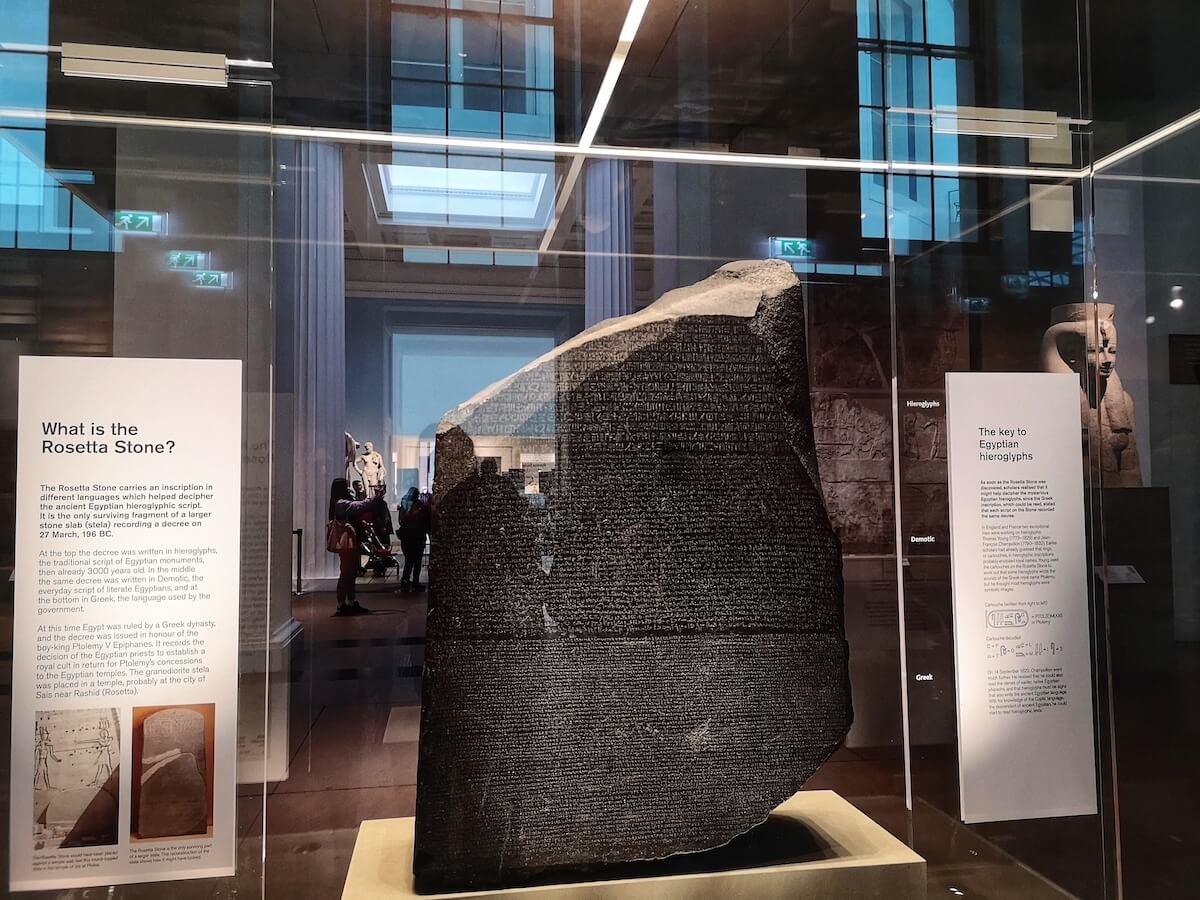

The Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is one of the most important objects in the story of ancient Egypt, and was the final key to deciphering the hieroglyphic language that was for centuries one of the most enduring mysteries of Egyptology. The massive stone was originally part of a larger slab known as a stela, and has an official decree voicing support from the priests of Memphis for king Ptolemy V inscribed onto its surface. Crucially, the decree is recounted in three languages - hieroglyphics, or the official language of state, Demotic, or the popular script used in everyday Egyptian life, and Ancient Greek - the language of bureaucracy. As Ancient Greek was known to scholars when the stone was found at the end of the 18th century, it became possible to crack the code of the hieroglyphs by comparing the texts. The painstaking process was completed by French philologist Jean-François Champollion, paving the way for a new understanding of Egyptian history, society and culture.

Where to find it: Room 4, Ground Floor, Level 0

Winged Lions of Nimrud

With developed societies extending as far back as 10,000 BC, the Middle East was the cradle of ancient civilisation - it’s to the ancient Mesopatamians that we owe vital human discoveries such as the wheel, agriculture, writing, mathematics and much more. Between the 10th and 7th centuries BC the Neo-Assyrian empire was the world’s most powerful state, extending all the way from the Mediterranean in the west to the Persian Gulf in the east and the Caucasus Mountains in the north, and a number of colossal sculptures surviving to this day are testament to the wealth and grandeur of this lost civilisation. These enormous 9th-century BC sculptures of winged lions with stylised human heads and long beards originally guarded the throne room of King Ashurnasipal the city of Nimrud (now in northern Iraq), and were believed to protect the city from harm.

Where to find it: Room 6, Ground Floor, Level 0

Bronze Portrait of the Emperor Augustus

Source: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0, author Aiwok

Source: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0, author Aiwok

The ancient Roman empire was one of the greatest and most powerful civilizations the world has ever known, and its story is inextricably tied up with the empire’s first and longest-serving emperor - Augustus. Rising to power in the aftermath of the bloody civil war that was unleashed in the wake of Julius Caesar’s assassination, Augustus proved to be a brilliant statesman and popular ruler. This remarkable bronze portrait captures the charisma, dignity and commanding nature of the man: his magnetic gaze will be sure to stop you in your tracks as you make your way through the museum. The sculpture was originally part of a full-body statue of the emperor that stood near the Roman empire’s southern border in Egypt. The area was captured by the Sudanese Kushite kingdom in 25 BC, and the Augustan statue dismembered, decapitated and buried. Augustus would only see the light of day again nearly 2,000 years later, when it was excavated by English archaeologist John Garstang in 1910.

Where to find it: Room 70, Upper Floor, Level 3

Lewis Chessmen

With its complex tactics and constantly shifting strategies, chess is one of the world’s most popular board games. It’s also one of the oldest, with origins extending back to 7th-century India. This set of ivory pieces is perhaps the most spectacular medieval chess set in existence, named after the Isle of Lewis in Scotland where they were discovered in the early 19th century. The figures are fabulously expressive and individualistic: look out for a warder (the equivalent of a castle or rook piece today) biting nervously on his shield, an apparently gloomy and contemplative queen and a king with a sheathed sword across his lap. The original owner of the set is unknown, but it has been theorised that they were in the possession of a Norwegian trader intent on selling them in Ireland, who was forced to bury them for safekeeping while en-route in Scotland. Whatever the truth, the Lewis Chessmen offer a fascinating insight into medieval European culture.

With its complex tactics and constantly shifting strategies, chess is one of the world’s most popular board games. It’s also one of the oldest, with origins extending back to 7th-century India. This set of ivory pieces is perhaps the most spectacular medieval chess set in existence, named after the Isle of Lewis in Scotland where they were discovered in the early 19th century. The figures are fabulously expressive and individualistic: look out for a warder (the equivalent of a castle or rook piece today) biting nervously on his shield, an apparently gloomy and contemplative queen and a king with a sheathed sword across his lap. The original owner of the set is unknown, but it has been theorised that they were in the possession of a Norwegian trader intent on selling them in Ireland, who was forced to bury them for safekeeping while en-route in Scotland. Whatever the truth, the Lewis Chessmen offer a fascinating insight into medieval European culture.

Where to find it: Room 40, Upper Floors, Level 3

Sutton Hoo Helmet

The Anglo-Saxon ship burial discovered at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk in 1939 was one of the most exciting archaeological discoveries of medieval British history, recently immortalised in Netflix drama The Dig. Amongst the hoard’s highlights is this jaw-dropping decorated helmet. It’s one of only four complete helmets to survive from the Anglo-Saxon period, and dates from the 6th or 7th century. Constructed from iron covered in copper alloy panels, designs on the helmet depict scenes of warriors and zoomorphic motifs, indicating that the helmet was a highly prestigious object, equal parts functional and aesthetic.

Where to find it: Room 41, Upper Floors, Level 3

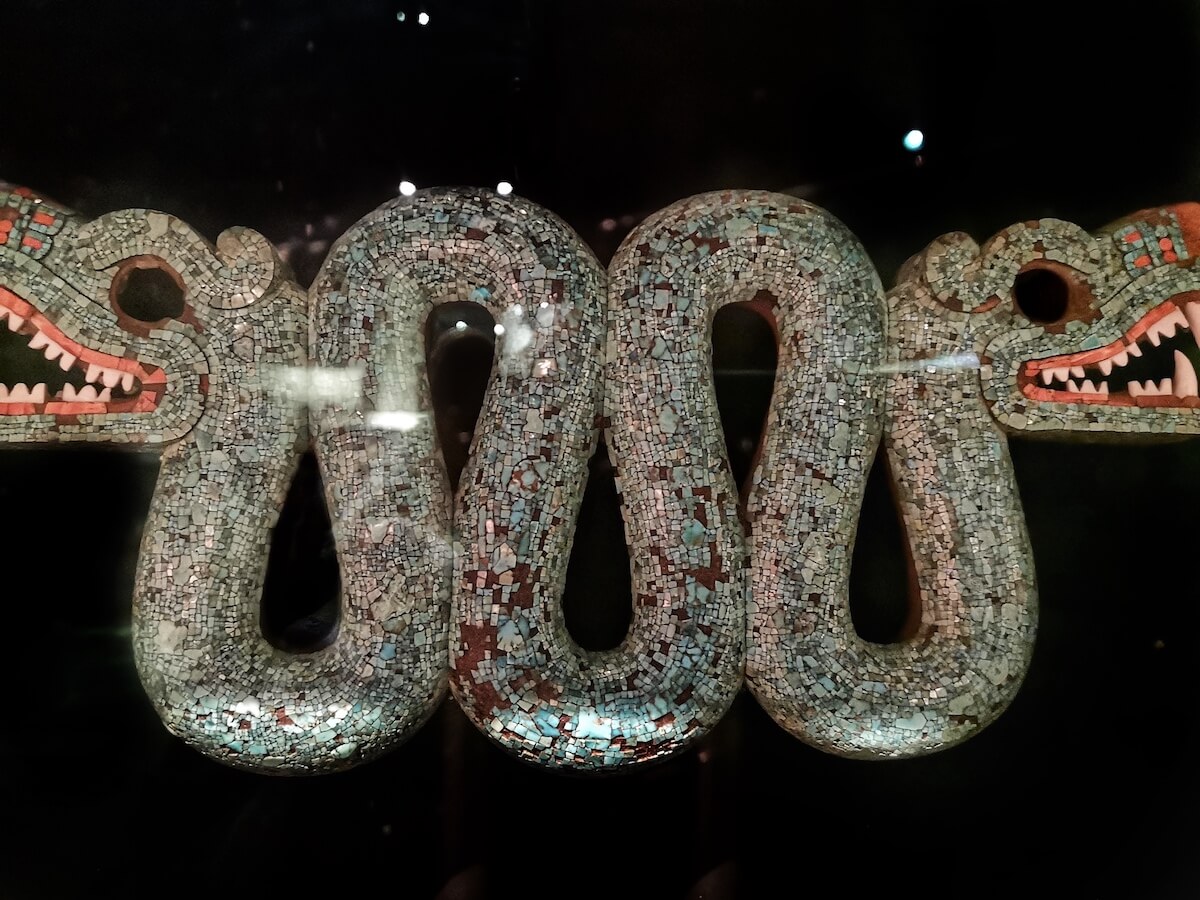

Mexican Serpent Mosaic

An iconic example of central-American art, this stunning double-headed serpent was meticulously crafted from over 2,000 pieces of turquoise mosaic and shells attached to a wooden framework. The snake was sculpted sometime in the 15th or 16th century, and reflects the religious significance that the reptile held for the Aztec people, whose most important god, Quetzlcoatl, took the form of a feathered serpent. The Aztec empire was the most extensive and largest in the Americas before the arrival of European invaders, and serpent sculptures survive from across their vast territories. The shimmering turquoise tiles and gleaming bared teeth seem to make the snake come alive, and it’s not hard to imagine the powerful effect this object would have had when worn during rituals and religious ceremonies.

Where to find it: Room 27, Ground Floor, Level 0

The Ife Head

Source: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0, author Saliko

Source: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0, author Saliko

This magnificent brass sculpture depicts the portrait of an Ooni, or sacred ruler of the Yoruba-speaking Kingdom of Ife in modern-day Nigeria wearing an elaborate headdress. The beautiful head dates from the 14th-century, and its striking naturalism and psychological intensity is characteristic of Ife sculpture. When this stunning object first went on display in the Museum in the 1930s it caused something of a controversy, with many viewers refusing to accept that 14th-century West African artists were capable of such realism. Today however the object is accepted for what it is - one of the shining cultural examples of a highly developed African kingdom.

Where to find it: Room 25, Lower Floor, Level -2

Through Eternity Tours offer expert-led guided itineraries through the colllections of the British Museums as well as many other sites in London. To find out more, check out the full range of our London tours here!