Magnificent Westminster Abbey is one of the finest examples of Gothic architecture in England, and is arguably the most important church in the nation - a spectacular stage for historical events for nearly 1,000 years. The soaring abbey - officially not a cathedral as it is not the seat of a bishop but instead managed directly by the Crown itself - was built during the reign of King Henry III in the 13th century to replace Edward the Confessor’s 11th century house of worship on the same site. It is a vast temple to living history, a history that continues in the series of royal coronations, weddings and funerals that have taken place here for centuries - every monarch since William the Conqueror has been crowned here. A new chapter will be etched into its stones in 2023, when King Charles III officially takes the throne. It’s easy to lose your bearings in the vast interior, so we’ve put together a list of things you need to see when visiting Westminster Abbey.

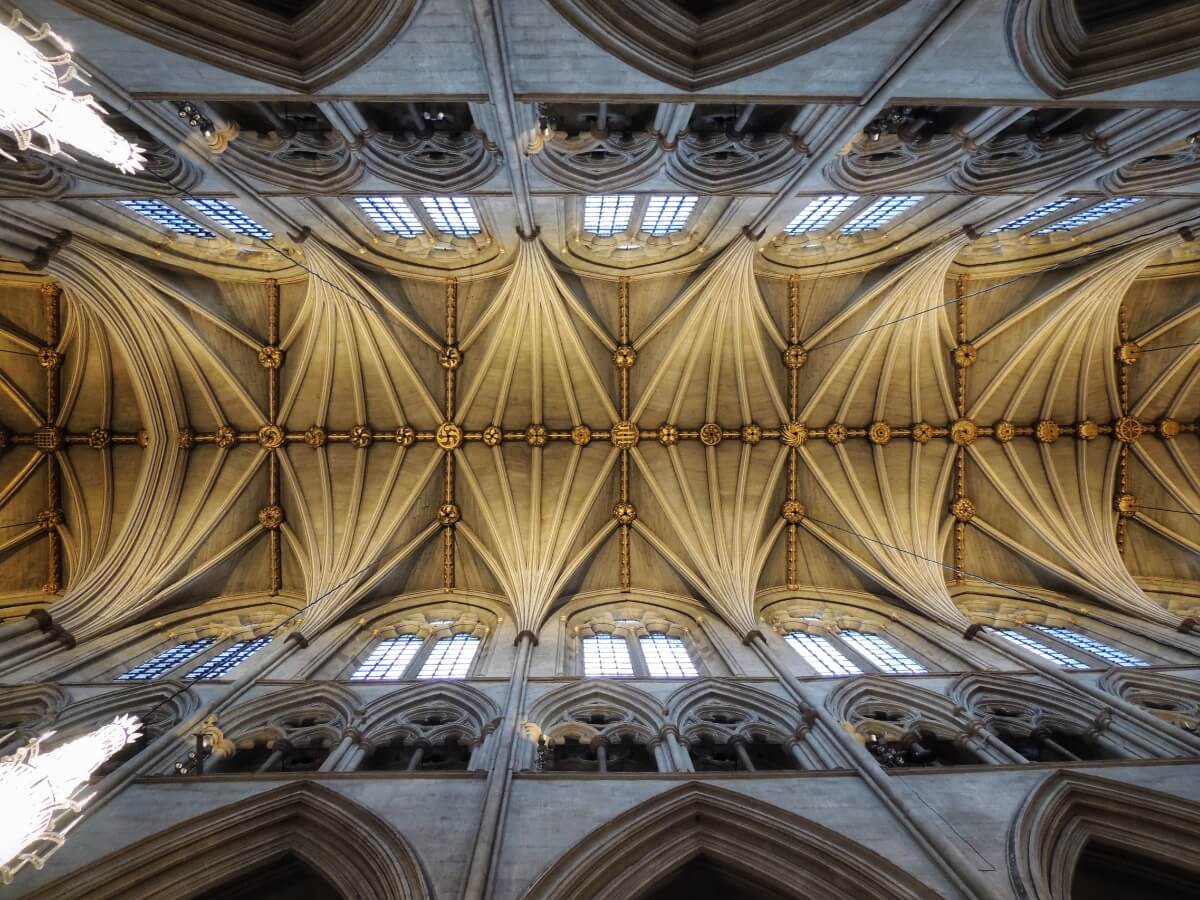

The Nave

The soaring nave of Westminster Abbey is the tallest Gothic nave in England, rising 101 feet from the church’s floor. Originally built by Edward the Confessor in the 1040s, the nave that we see today is the product of Henry III’s rebuilding, although when the king died in 1272 works were far from complete. It was only when master mason Henry Yevele took up his chisels in 1376 that the work on the nave restarted once again, and it took a further 150 years to complete. The soaring height of the nave is made possible by a series of flying buttresses on the exterior of the abbey, supporting the huge outward pressure being exerted on the walls of the church. The nave extends for 166 feet from the Great West Door as far as the choir.

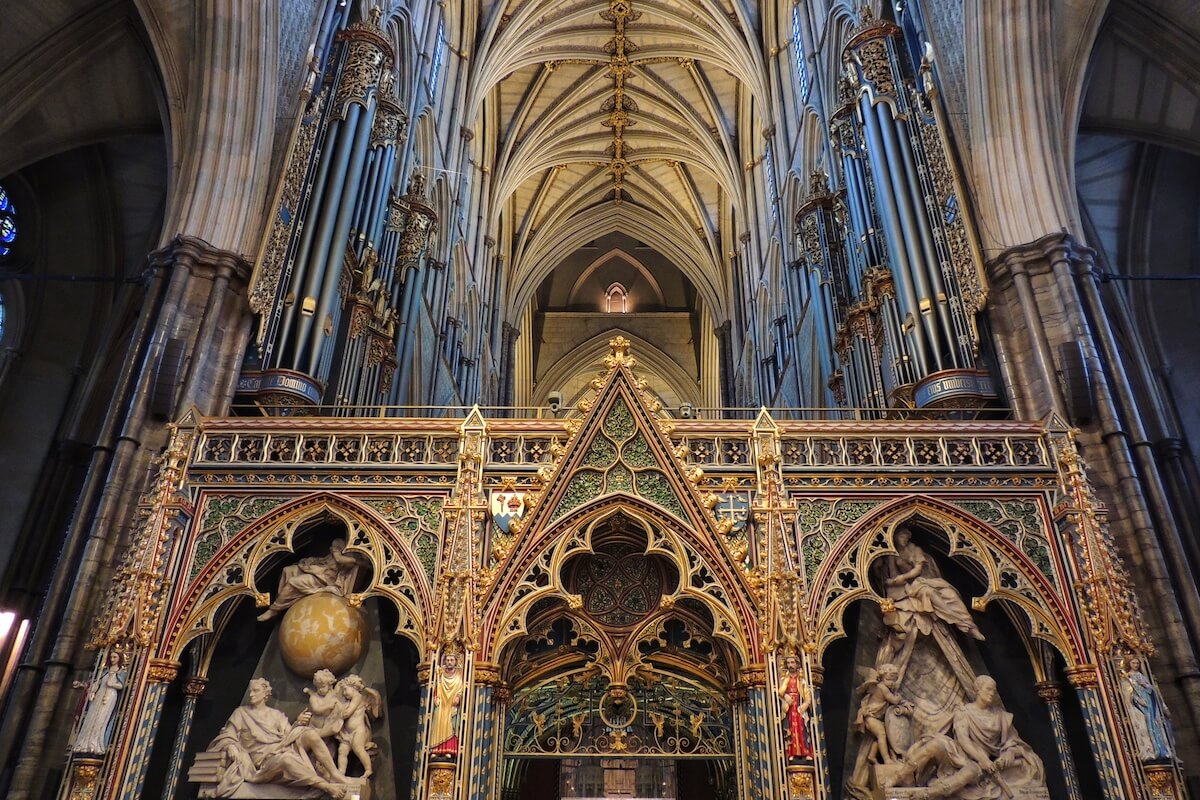

The Rood Screen

Dividing the nave from the Quire, this fabulously decorated choir screen is a masterpiece of English church architecture, and features a series of pointed arches, quatrefoil cutouts and spires studded with sculptures. The rood screen was a common feature of medieval church architecture, and served to provide a barrier between the nave, where the congregation would gather, and the chancel, where the sacred rites and offices would be carried out - a metaphorical division between the sacred and profane worlds. Set into the screen on the left is a monument to the scientist Sir Isaac Newton, who is buried here. To the right, a matching monument memorialises James Stanhope, an 18th century soldier and politician. Above the choir screen is the Abbey’s famous organ.

The Quire

The performance of sacred music is a central aspect of life in Westminster Abbey, and the church’s iconic Quire is where the musical magic happens. Members of the choir occupy a series of beautifully decorated choir stalls running along both sides of the abbey’s central aisle, 19th century replacements of the original stalls. Important state officials and members of the church hierarchy also have stalls here, which they occupy during services. The choristers are taken from the students of Westminster Abbey Choir School, a boarding school adjacent to the abbey where choir boys have been educated since the Elizabethan era.

Poet’s Corner

Over 100 eminent authors are either buried or have memorials dedicated to them in this characterful corner of Westminster Abbey that has become an essential pilgrimage destination for literature lovers from around the world. The tradition of Poet’s Corner began in the year 1400, when the great poet and author of the Canterbury Tales Geoffrey Chaucer was buried here - not in honour of his literary abilities but rather due to his employment as Clerk of the King’s Works. Two centuries later, the poet and favourite of Queen Elizabeth Edmund Spenser requested that he be buried in the Abbey beside Chaucer, and numerous eminent English writers have followed. Here you’ll find the graves of Ben Johnson and John Dryden, Robert Browning and Samuel Johnson, Charles Dickens and Rudyard Kipling, Thomas Hardy and Alfred Lord Tennyson amongst many others. Breaking the writers’ monopoly, you’ll also find actor Laurence Olivier and composer George Friedrich Handel here.

The Lady Chapel

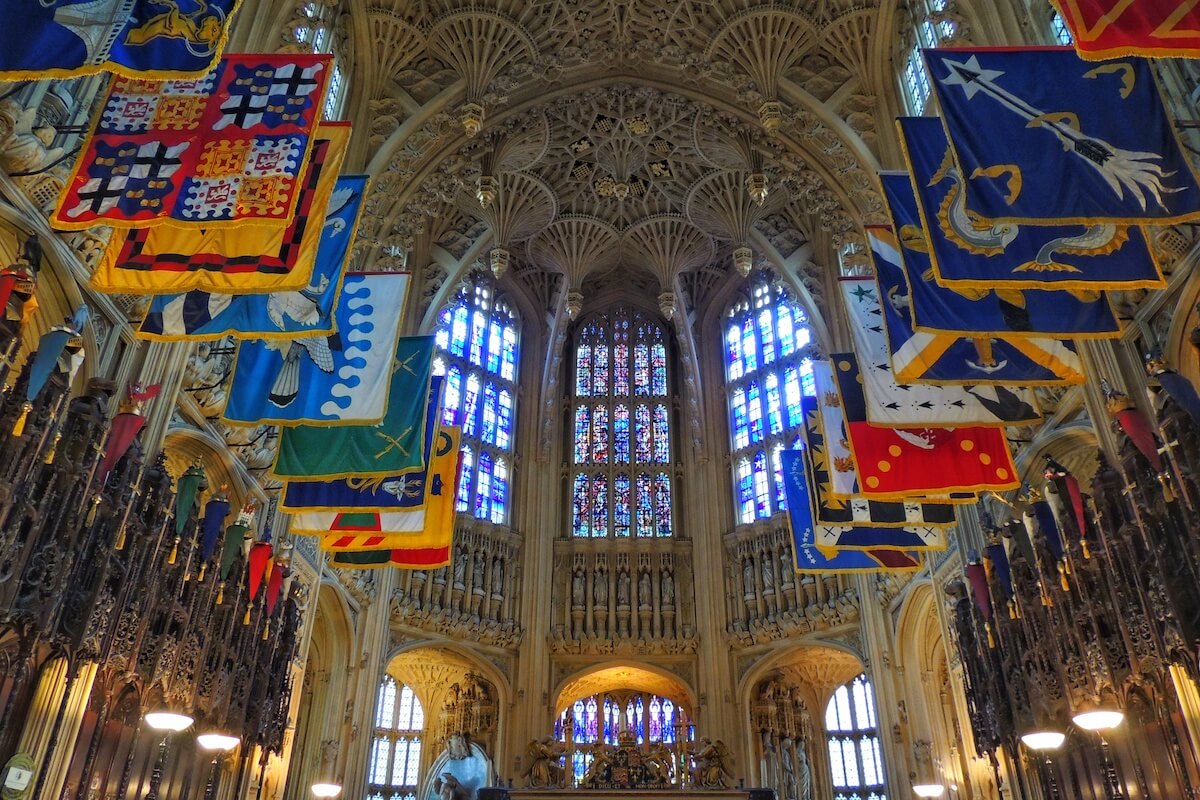

The glittering highlight in Westminster Abbey’s array of architectural gems and final resting place of no fewer than fifteen monarchs, the stunning Lady Chapel was begun by King Henry VII in 1503 and completed 13 years later, after his death. The superb, dizzyingly complex fan-vaulted ceiling is arguably the finest example of late-medieval architecture in Britain. Statues of 95 saints line the walls, while intricately carved wooden stalls feature an array of imagery including animals and monsters, mermaids and dragons. The tomb of King Henry himself occupies pride of place at the eastern end of the chapel, a stunning Renaissance creation by Florentine sculptor Pietro Torrigiano (who had been forced to flee his native city after breaking Michelangelo’s nose) featuring bronze effigies of the king and his queen, Elizabeth of York. The Lady Chapel is also home to the tombs of Queen Elizabeth 1 and Mary Queen of Scots, cousins and implacable enemies, divided by faith in life but buried beside one another in magnificent tombs to either side of the chapel.

In 1725 King George 1st revived the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, an elite military order of knights; each member is accorded the honour of a stall in the Lady Chapel, where their coat of arms hang on banners until their death.

Shrine of Edward the Confessor

When Edward the Confessor died in 1065, he was laid to rest at the heart of the Abbey that he commissioned. Over the coming centuries his body was to be exhumed numerous times in attempts to verify the saintly incorruptibility of his body. In the course of the rebuilding of the Abbey ordered by King Henry III, a devoted admirer of the Confessor, Edward’s remains were moved, or translated, to a stunning new shrine that the King had built expressly for the purpose at the centrepiece of the magnificent new Gothic church. Henry drafted in the finest artisans from Italy for the job, and what they came up with was awe-inspiring. An intricately carved stone base inlaid with Cosmatesque detailing supported a golden feretory carrying Edward’s tomb, flanked by statues and surmounted with an elaborate canopy. King Henry III himself carried Edward’s coffin to its new resting place, and when Henry’s time came in turn he was buried alongside his idol. The shrine was badly damaged during the Reformation, before being restored by the resolutely Catholic Queen Mary 1. Edward’s shrine is located behind the High Altar.

The High Altar

Photo by14GTR - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, wikimedia

The High Altar of Westminster Abbey dates from 1867, designed by renowned neo-Gothic architect George Gilbert Scott. The Cosmati pavement leading up to the altar is the finest example of this intricate medieval technique in Britain, installed by Italian craftsmen in 1268 on the orders of King Henry III.

The Diamond Jubilee Galleries

Make the climb up to the Triforium level of the Abbey to visit the recently opened Diamond Jubilee Galleries. Triforium is the name given to an arcaded gallery that runs above the nave of a church, and the Triforium of Westminster Abbey dates from 1250. Various paintings, tapestries, sculptures and regal paraphernalia recount the history of the Abbey and its central role in the story of the English monarchy, including a stunning funeral portrait of Henry VII and the Westminster Retable, originally destined for the Abbey’s High Altar when it was painted in the 1270s, and currently the oldest surviving altarpiece in Britain. Make sure to peek out through the triforium’s arcaded openings that look down onto the nave for spectacular views of the Abbey from on high.

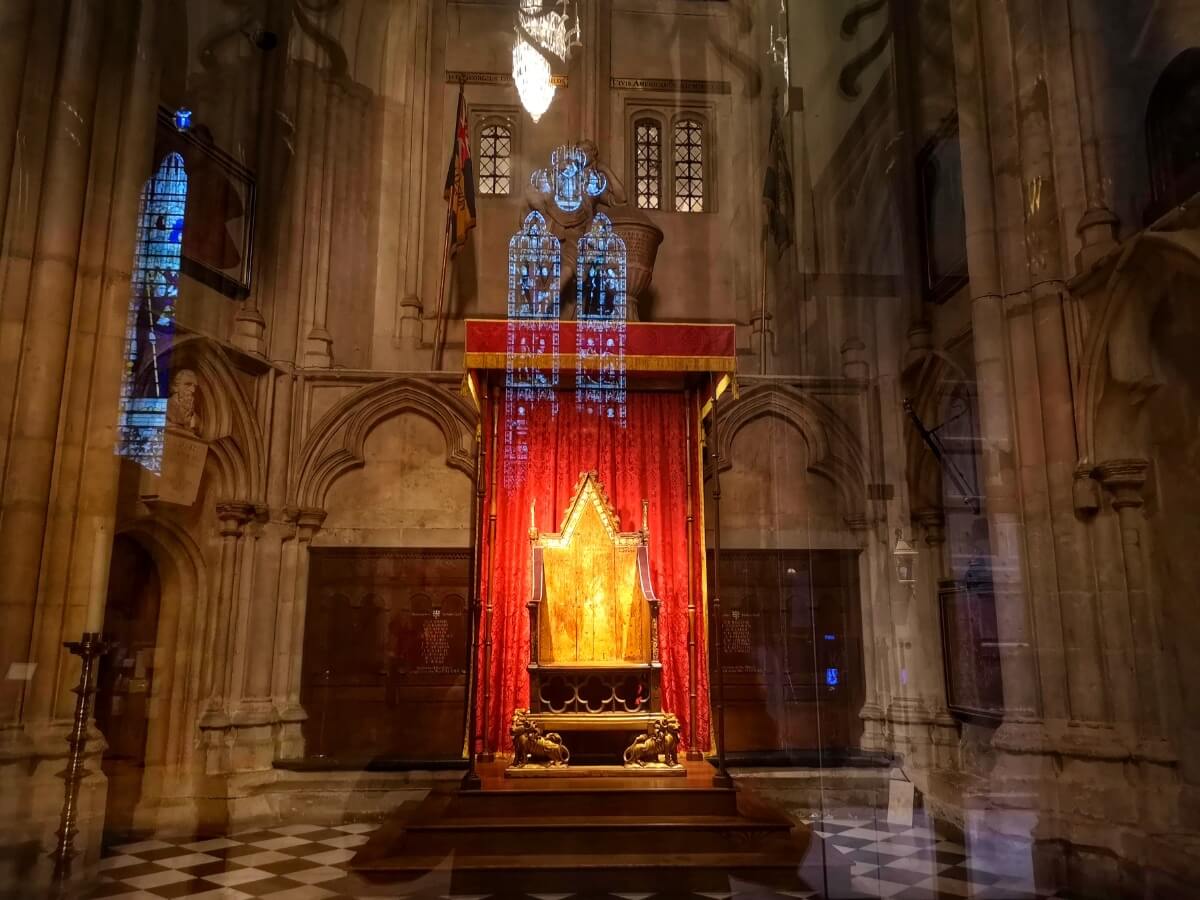

The Coronation Chair

As its name implies, Westminster Abbey’s Coronation Chair takes centre stage during coronation ceremonies for English monarchs, and every king or queen to take the throne for over the last 700 years has sat in the historic chair. The once fabulously decorated wooden chair has taken its fair share of damage over the centuries, but the battered and graffiti-covered seat positively drips with history. For seven centuries the iconic Stone of Scone resided on the Coronation chair after king Edward I stole it from Scotland in 1296. The Stone was returned to Edinburgh Castle in 1996, but is slated to return to Westminster Abbey to play its part in the coronation of King Charles III in May 2023.

The Queen’s Window

One of the newest additions to the venerable Abbey is the Queen Elizabeth Window, installed in 2018 to a design by renowned modernist artist David Hockney to celebrate the long reign of Queen Elizabeth II. The vibrant stained glass stands out in immediate contrast to the more sober palette of the historic windows to either side, and instead of depicting an overtly religious or regal subject takes inspiration from the natural world - a pastoral scene of flowers and plants that recalls the fauvist expressionism of Henri Matisse.

Pyx Chamber

One of the oldest parts of Westminster Abbey, the atmospheric Pyx Chamber is a small vaulted room in the Abbey’s Undercroft, beneath where the monks slept. Dating from the 1070s, the room was transformed into a treasury in the 1200s - the word pyx derives from wooden boxes that were kept in the chamber containing silver and gold pieces used in tests to determine the purity of coinage. The imposing oak doors date from the 14th century.

Through Eternity Tours offer a range of expert-led itineraries in London. Explore spectacular Westminster Abbey and discover its secrets on our Best of London tour.