Beware the Ides of March…On March 15th, 44 BC the course of Roman (and perhaps world) history changed forever. The all-powerful Julius Caesar, just declared dictator for life and seemingly on the fast track to absolute sovereign power, was cut down in the Theatre of Pompey by a group of 60 senators unwilling to stand by as the Roman Republic descended into autocratic rule. Ironically the assassination of Caesar accelerated rather than halted the collapse of Republican Rome. Civil war ensued, and from its ashes rose the first Emperor of the vast Roman state: Gaius Octavius, known to history as Augustus. But what exactly are the Ides of March, and how did events unfold on that fateful day in 44 BC?

To celebrate the launch of our Julius Caesar Virtual Tour, where we follow in the footsteps of the dictator, this week our blog is looking in detail at the Ides of March and the events that led to his assassination.

What are the Ides of March?

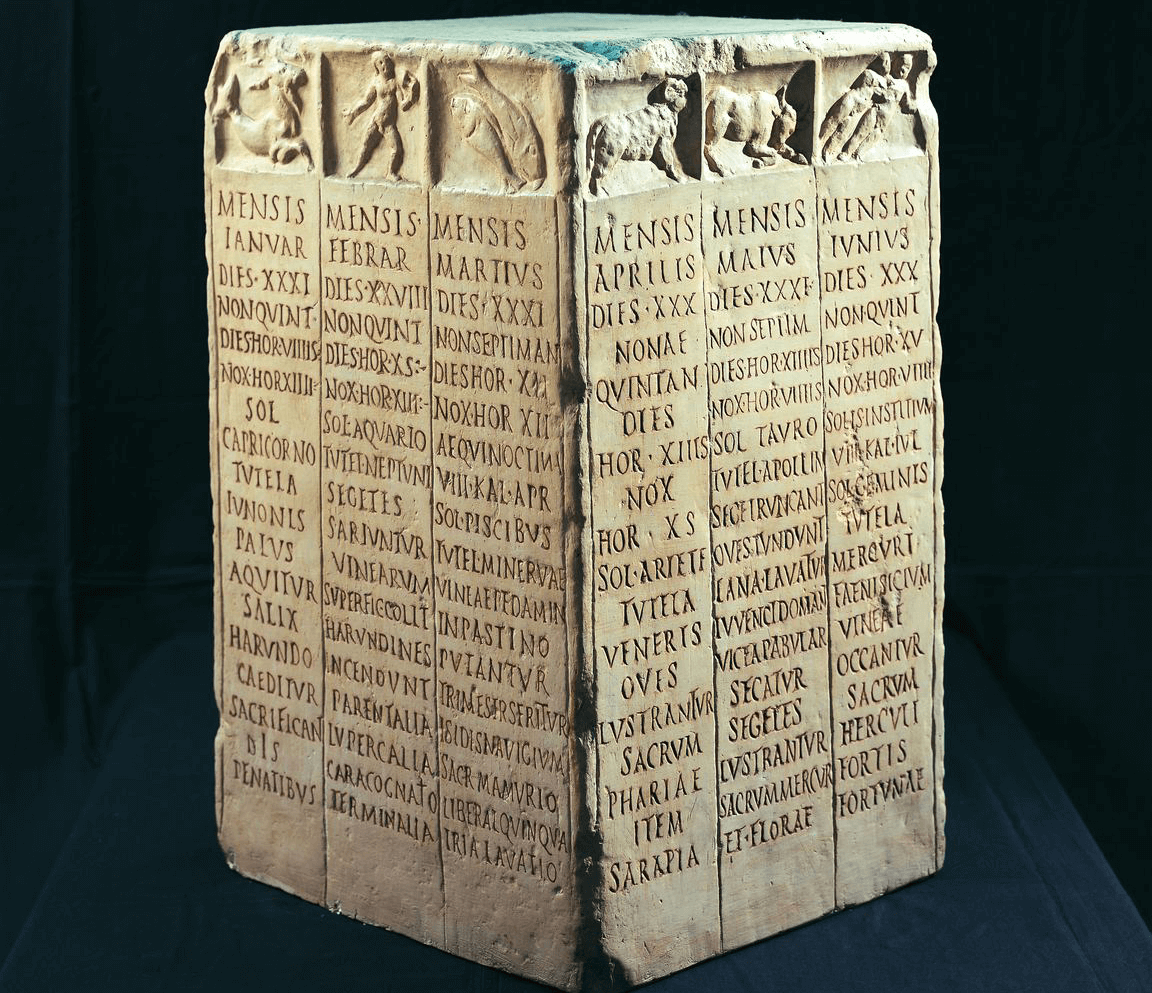

The Menologium Rusticum Colotianum, an ancient Roman calendar

The Menologium Rusticum Colotianum, an ancient Roman calendar

As with so many iconic phrases that have become common cultural capital across the globe, the portentous warning ‘Beware the Ides of March’ is an invention of William Shakespeare. In his dramatic rendering of Caesar’s assassination and the ensuing civil war, a soothsayer utters his immortal warning to the dictator as he makes his way through an adoring throng.

Caesar unwisely dismisses the intervention as the ramblings of a ‘dreamer’, but one can hardly have expected him to take the soothsayer’s forecast to heart: despite their portentous overtones to our 21st-century ears, there is nothing intrinsically inauspicious about the ides of March. The ides, in fact, merely refer to the somewhat complicated way the passage of the weeks and days were calculated in ancient Rome.

Each month possessed three fixed reference points: the kalends on the first day, the ides in the middle of the month, and the nones midway between the two. Rome’s ancient calendar was a lunar one, and the 3 reference points related to the cycle of the moon - the ides marked the first full moon of the month. To track the passage of the days, days were counted back from the nearest reference point. In March the nones fell on the 7th, so days 2-6 were referred to as ‘before the Nones.’ Days 8-14 were ‘before the ides’ which fell on March 15th, and the remaining days were described as ‘before the kalends’ of the following month.

Despite being just another way of saying March 15th, the ides did have some symbolic and cultural resonance in antiquity. The ides of every month were sacred to the god Jupiter, and a procession of sacrificial sheep made its way through Rome to the Citadel to celebrate the occasion. The Ides of March also marked the feast of Ana Perenna, the culminating event of ancient Roman celebrations of the New Year which originally was celebrated at the beginning of March.

Caesar’s Rise to Power

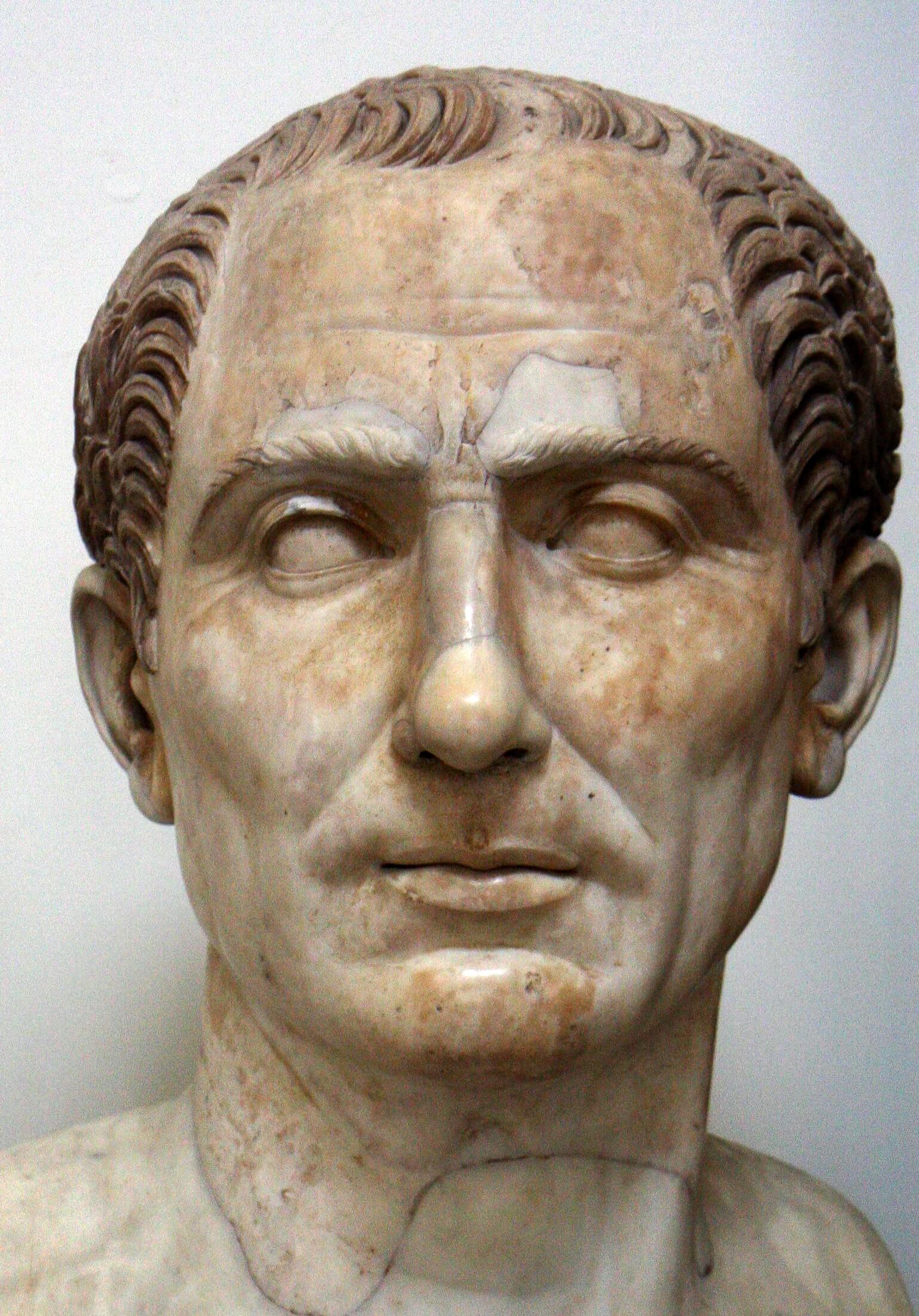

Portait of Julius Caesar from the Naples Archaeological Museum

But the Ides of March will be forever be associated with Julius Caesar. Even if your knowledge of ancient Rome barely extends beyond Russell Crowe’s gladiator bellowing “Are you not entertained!?” into the Colosseum’s yawning bleachers, it’s a fairly sure bet that you’ve heard of our Julius.

Born into the aristocratic Julii family in (probably) 100 BC, Caesar’s rise to power and influence was nothing short of astonishing. Giving a foretaste of his indomitable spirit and sheer bloody mindedness, Caesar was captured by pirates on a study trip to Rhodes when in his early 20s. After securing his release by raising the ransom himself (which he insisted be set higher than the initial asking price of the gobsmacked pirates), Caesar, who held no military or public office, procured ships and a navy, pursued his ex-captors, captured them, and had them crucified en-mass. This was one man not to be messed with.

Military commissions and increasingly prestigious political offices soon followed. In 69 BC he was elected Quaestor, and 6 years later somehow managed to get himself made the Pontifex Maximus, or High Priest. 62 BC finds him elected praetor, and the governorship of further Spain soon followed. By this time Caesar was already a highly polarising figure in Rome, racking up enormous debts in his implacable quest for power.

Caesar’s election as consul in 59 BC led to further enrichment, helped along by a secret pact with the military general Pompey and politician Marcus Licinius Crassus - the first triumvirate. His subsequent triumphant 8 year campaign to conquer and subjugate Gaul and his audacious invasion of Britain cemented his position at the apex of public life. But as his power increased, so his enemies multiplied.

Alea Iacta Est: Crossing the Rubicon

![]()

Jean Fouquet, Caesar Crossing the Rubicon, 1475 (photo Wikimedia commons)

Ordered by the Senate to relinquish his military command and return to Rome, Caesar, fearful of being exposed to prosecution for corruption and abuse of power at the hands of hostile antagonists in the Senate, made the fateful decision to cross the Rubicon river into Italy on January 10, 49 B.C. Marching towards Rome with his loyal legion in tow was an overt act of insurrection against Rome’s civic authority, and civil war inevitably ensued - but there was only ever one winner. Caesar’s crack legions of military veterans crushed his one-time ally Pompey’s armies in conflicts across the Roman world, and after a decisive victory in the battle of Pharsalus the stage was finally clear for their commander in chief to return to Rome in triumph.

Caesar was now the de-facto leader of the government, and began reshaping the empire in his own image via a series of radical reforms and extensive building programmes. In January or February of 44 BC Caesar was declared (or had himself declared) dictator perpetuo, or dictator for life by a cowed Senate, carried through on a wave of populist support.

Statue of Julius Caesar in the Roman Forum as dictator perpetuo

Statue of Julius Caesar in the Roman Forum as dictator perpetuo

But his enemies in the establishment were multiplying. Alarmed at what Caesar’s dictatorial and monarchical ambitions would mean for the Roman Republic, a group of prominent senators led by the staunchly anti-monarchical Marcus Junius Brutus (not quite Caesar’s bosom buddy, as Shakespeare would have it, but by turns an admirer and long-time critic), and his brother-in-law Gaius Cassius Longinus determined that there was only one option left on the table: assassination.

The Plot

Coin commissioned by Brutus to commemorate Caesar's assassination, emphasising libertas

With the course open to them clear, Brutus and Cassius began recruiting other senators to their cause. To many Roman eyes and ears the notion of a king remained a poisonous one, invoking memories of the brutal and corrupt Tarquins who had been overthrown before the founding of the Roman Republic nearly 500 years earlier.

It seems that Brutus and Cassius had little difficulty in convincing other high ranking members of Roman society that Caesar’s murder was the only way to avoid a return to autocracy and the destruction of Rome’s treasured Republican institutions. Given the laundry list of enemies and personal animosities Caesar had accrued during his relentless rise to power, there were also plenty of high-ranking Romans looking for any excuse to avenge themselves on the dictator. If idealism was the conspiracy’s right hand, opportunism was its left.

Caesar was due to depart on a military campaign against the Parthians before the April kalends, and so the timing for the assassination attempt was fixed: the Ides of March.

The Assassination

Vincenzo Camuccini, The Death of Julius Caesar, 1825 (photo Wikimedia commons)

Vincenzo Camuccini, The Death of Julius Caesar, 1825 (photo Wikimedia commons)

Beyond Brutus and Cassius, there was a third ringleader in the plot. This was Decimus Brutus who, unlike his distant cousin Marcus Junius or Cassius, was a personal friend and ally of Caesar. Decimus' reason for joining the venture is not entirely clear, but it has been speculated he had perhaps felt slighted by the dictator’s refusal to honour him with a triumph in celebration of his military exploits and the stalling of his career advancement prospects.

Decimus’ intimate relationship with Caesar ultimately proved essential in the successful execution of the assassination attempt. The ancient historian Nicolaus of Damascus recounts how rumours and ominous portents had recently disquieted Caesar’s wife Calpurnia and Caesar’s friends - something seemed to be in the air. In deference to Calpurnia’s misgivings, Caesar had decided not to leave home on the ides to attend the Senate.

Edward Poynter, Calpurnia and Caesar on the The Ides of March, 1883 (photo wikimedia commons)

A Caesar no-show on the ides would have proved disastrous for the conspirators, and so Decimus was dispatched to convince Caesar to make an appearance. Decimus played his role to perfection, admonishing Caesar for listening to the fears of women and idle gossip before escorting Caesar personally to the Theatre of Pompey where the Senate was in session.

The conspirators were ready and waiting, short daggers concealed beneath their togas. One of their number, Tillius Cimber, approached Caesar with a petition on behalf of his exiled brother, pulling impertinently at the dictator’s clothes. This was the cue for the beginning of the assault, Servilius Casca striking the first blow.

Annual re-enactment of Caesar's assassination in Rome's Largo Argentina

Annual re-enactment of Caesar's assassination in Rome's Largo Argentina

The assassins had quietly formed a perimeter around their target, meaning there was no escape. Caesar’s cry of ‘why, this is violence’ fell on deaf ears as the conspirators stabbed, and stabbed again. Despite managing to wound Casca with a stylus, Caesar was doomed. Covering his face with his toga, he fell at the feet of a statue of Pompey, his long-vanquished rival. The dictator was dead. But not forgotten.

The Aftermath

Rome's Largo Argentina, site of Caesar's assassination in the ancient Theatre of Pompey

Rome's Largo Argentina, site of Caesar's assassination in the ancient Theatre of Pompey

The elation of the conspirators at the success of their plan was destined to be short-lived. Caesar’s powerful allies Mark Antony and his adopted son Octavius ensured that the Republican faction would not go unopposed, whipping up public outrage at the assassination of the highly popular and populist Caesar at the hands of a group of out-of-touch elites. After yet another civil war in which the forces of Brutus and Cassius were defeated, Rome’s move towards autocratic rule would become permanent in the rise of Octavius to become Rome’s first and perhaps greatest emperor: Augustus. The ides of March would echo down the centuries as one of the great turning points in history: the Republic was dead, and an Empire was born.

If you’d like to learn more about the fascinating life of Julius Caesar and his fundamental role in the course of Roman history, then be sure to check out our Rome in the Age of Julius Caesar Virtual Tour for a detailed look at power and dictatorship in the ancient city in the company of an expert!