If you’ve ever found yourself struggling through the Colosseum’s ancient ruins under a blazing summer sun, you’ll know that it can feel like one of the hottest places on earth. It’s easy to imagine that things were a lot worse for the 50,000 spectators who thronged the ancient arena’s marble bleachers hoping to sate their bloodlust with the brutal sight of wild beasts, prisoners and gladiators butchered for their entertainment in antiquity. As the sun beat down and was reflected off the blinding sand and stone into the massive crowds, without some kind of shade it must have been an unbearable experience.

As any self-respecting fan of Ridley Scott’s epic movie Gladiator will know however, our luxury-loving ancient forebears would never have stood for such a state of affairs. Incredibly, the massive Colosseum was covered with a roof that protected spectators from the relentless Italian sun, allowing them to settle back and drink in a day of blood-sport in shady bliss. OK, so everyone’s favorite sword-and-sandals Russell Crowe vehicle might not be an exemplar of historically accurate film-making, but its spectacular portrayal of a fabric awning shading the crowd clamoring to get a glimpse of Maximus Decimus Meridius wreaking brutal revenge on the criminally insane emperor Commodus is actually not far wide of the mark.

By the time the Flavian Amphitheatre was completed under the reign of the emperor Titus in 80 AD, elaborate moveable fabric roofs were commonplace in theatres and amphitheaters all across the empire – a fragment of marketing graffiti recovered from Pompeii even boasts that ‘there will be awnings’ (vela erunt) at the next games there in an attempt to drum up business.

By the time the Flavian Amphitheatre was completed under the reign of the emperor Titus in 80 AD, elaborate moveable fabric roofs were commonplace in theatres and amphitheaters all across the empire – a fragment of marketing graffiti recovered from Pompeii even boasts that ‘there will be awnings’ (vela erunt) at the next games there in an attempt to drum up business.

Awnings feature heavily in ancient literary sources too. The chronicler Suetonius reports that the sadistic Caligula (who was so keen on the games that he liked to personally compete in rigged gladiator combat) often retracted the awnings of the temporary wooden amphitheatre that preceded the Colosseum at the hottest part of the day without warning, commanding the audience to remain unmoving beneath the burning midday rays on pain of death. A generation later, the equally unhinged Nero reportedly decked out Rome’s Theatre of Pompey with a purple awning bearing a massive representation of himself driving the chariot of the Sun.

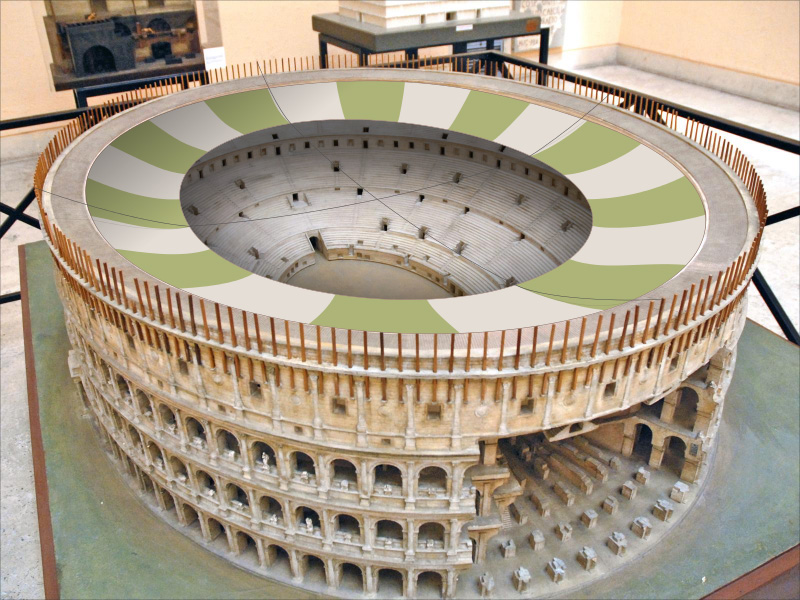

But as the largest amphitheater in the ancient world, successfully providing cover for the nearly 200 feet tall Colosseum was an altogether different kettle of fish. In a mind-boggling feat of engineering, Roman experts came up with an enormous retractable awning that would be the envy of many state-of-the-art sports stadiums even today. Exactly how they did it remains a matter of speculation, but research in the last 20 years has given us a good idea of what it must have been like.

The awning was known as the velarium, and was made up of several separate tapered pieces of fabric carried high above the amphitheater by a complex web of ropes. This rigging was supported by 240 evenly spaced wooden masts that sprang from the top tier of the entire structure, and if you get the chance to tour the upper levels of the Colosseum you can still see the remains of the projecting corbels (brackets) and sockets that buttressed them. The awning didn’t extend over the entire footprint of the Colosseum, but instead sloped downwards towards a large central opening that made the whole canopy more flexible - the spoke-like rigging extending from the masts terminated in an elliptical rope that defined the shape of the opening. And so even whilst the spectators in the seating area (cavea) were bathed in shadow, the action taking place on the sand of the arena was open to the sky and dramatically spot-lit by the sun - think of it as a massive ephemeral version of the oculus that spectacularly pierces the roof of the Pantheon in central Rome.

The awning was made out of the same linen or canvas fabric that was used by ancient shipbuilders to fashion sails for their galleys, and the word velarium actually derives from the Latin word for sail. It was for good reason that experienced sailors were entrusted with operating the awning, qualified by dint of their experience with sails and rigging on the high seas. A special detachment from the naval fleet at Misenum near Naples was stationed in barracks around the corner from the Colosseum for this very purpose, the Castra Misenatium.

From their panoramic perches high up on the amphitheater’s top tier, the sailors manipulated the infinity of ropes that extended and retracted the unwieldy awning with admirable dexterity – to avoid damaging the velarium, it wasn’t raised at all when high winds or rain was in the offing, leaving the spectators at the mercy of the elements. Working the velarium was a highly prestigious assignment for any slave who was conscripted into the Roman navy, but many of their bedfellows at the Castra Misenatium weren’t so lucky – the barracks were also home to sailors awaiting their turn in the bloody and fatal mock sea-battles (naumachiae) that formed a dramatic part of the earliest stagings of the Roman games at the Colosseum after its inauguration in 80 A.D.

The velarium brilliantly exemplifies both the ancient Roman capacity for practicality and its insatiable taste for drama. On the one hand the velarium was an ingenious technical solution to a practical problem; but the Colosseum’s awning was far more than a merely functional piece of engineering. Transforming the spot-lit arena floor into a cathedral of light emerging from the surrounding shadows, the effects of the velarium must have elevated the already dramatic spectacles of life and death taking place on the sands before the eyes of the audience to an almost unbearable fever-pitch.

Learn more about the velarium and other fascinating historical nuggets in the company of an archaeologist on an expert-led Colosseum tour with Through Eternity.