Updated 18 February 2025

Few images of ancient Rome are as iconic as the gladiators. We can all picture in our mind’s eye those fierce warriors, bulging muscles slicked with sweat and blood, battling desperately for survival in the grand amphitheater of the Colosseum. These brutal contests, equal parts bloodsport and elaborate public spectacle, captivated Roman audiences for centuries. But who were these fighters, and what truly happened within the towering stone edifice that could hold over 50,000 spectators?

To help prepare you for your visit to the Colosseum, we’re taking a deep-dive into the history of gladiatorial combat, from its origins to the identities of the combatants, from the intense training that the gladiators underwent before ever getting near the arena to the high-stakes battles that played out there.

Step into the world of Rome’s most legendary warriors with us, and discover the fascinating story of the men who made the ancient games possible. Here's what we'll cover:

- Gladiator combat in the ancient world

- What took place at the Colosseum?

- Who were the gladiators?

- How did the gladiators train?

- What did the gladiators eat?

- How did the fights in the arena unfold?

- What happened to the winners and the losers?

Gladiator combat in the ancient world

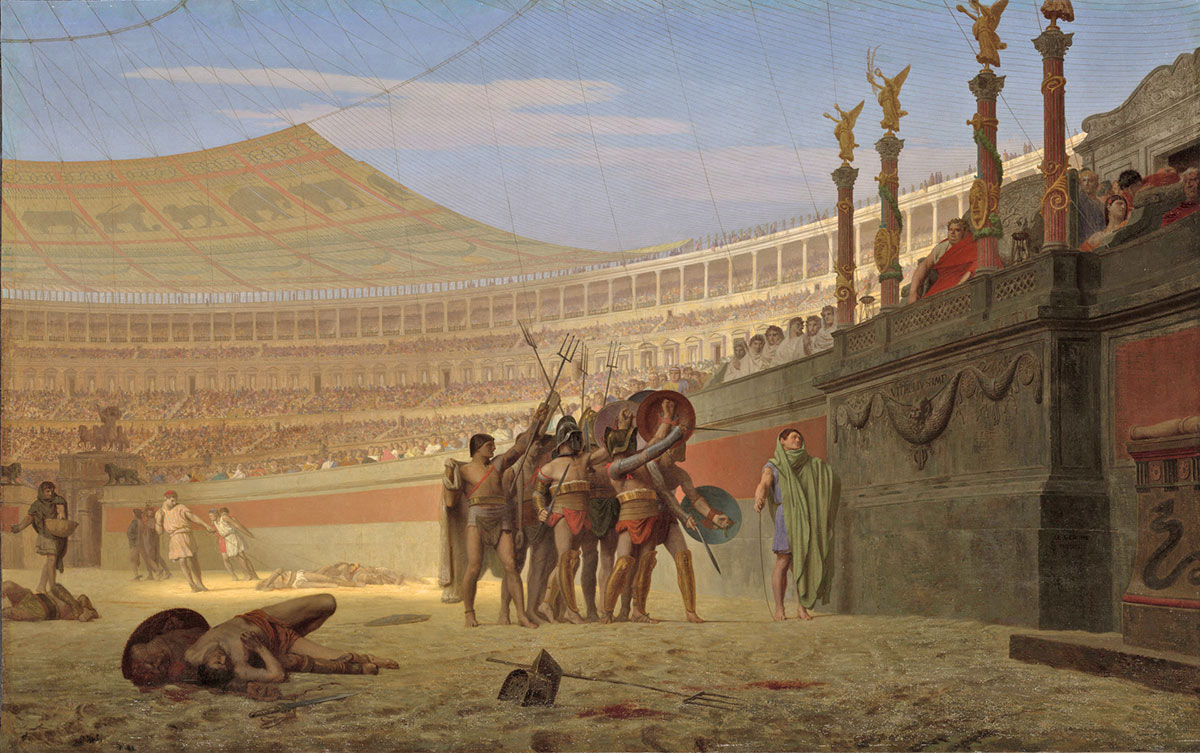

Gérôme, Ave Caesar! Morituri te salutant, 1859

Gérôme, Ave Caesar! Morituri te salutant, 1859

Gladiatorial combat can be traced back to ancient Etruscan funeral rites, and the earliest recorded example of the practice took place in 264 B.C. when the sons of one Iunius Brutus put on a show to honour their deceased father. It wasn’t until 105 B.C. that the first official games were held, but mortal combat had become an increasingly popular form of entertainment for the city’s aristocracy as Rome’s Republican era reached its zenith.

By the early years of the Imperial period the city still lacked a dedicated space for their performance. That all changed in 72 AD, when the emperor Vespasian commissioned the awe-inspiring Flavian Amphitheatre - built as a gift to the people on the site of the deposed Nero’s luxurious Domus Aurea.

The massive, iconic building took just ten years to complete, and regularly packed in crowds upwards of 65,000 people into bleachers towering high into the Roman sky. To inaugurate its completion, the emperor Vespasian’s son and successor Titus celebrated with 100 days of non-stop games including exotic animal hunts, executions, music, and of course gladiator battles.

The dramatic gladiator contests quickly became a powerful propagandistic tool, demonstrating the astonishing might of the Roman Empire and showing the city’s population that their Emperor himself personally cared for their well-being. In the words of one Through Eternity guide, the games were ‘weapons of mass distraction,’ regularly staged in an attempt to keep the people sated on a rich diet of bread and circuses. The tradition of the games would continue here for five centuries as a key guarantor of social cohesion in the Imperial capital.

What took place at the Colosseum?

The interior of the Colosseum today

The interior of the Colosseum today

On the morning of the games spectators flooded in through 80 different entrance arches and up countless stairways to their allocated seats, where they awaited the procession marking the opening of the games to the sound of trumpets and fanfares. At the end of the procession the gladiators emerged, the star attractions that the masses of spectators had come to see.

Their turn in the arena would only come later, though, as the games usually began with elaborate wild-animal hunts in the morning. Read more about the role of wild animals in the Colosseum here. During the midday interval, the so-called ludi meridiani took place, where condemned criminals were thrown to the surviving beasts or made to re-enact grisly ancient myths. Bizarrely to our modern sensibilities, burlesque comedies were staged to break up the rhythm of slaughter. The climax of the day came during the afternoon however, when the stage was cleared for the main event: gladiator combat.

The gladiator battles that pitted armed combatants against one another in brutal but often highly choreographed duels were by far the most popular kind of entertainment that unfolded in the Colosseum. Gladiators often enjoyed astonishing public acclaim: their names and deeds were depicted on a vast range of artefacts and artworks, and ancient inscriptions show that they were the sex-symbols of antiquity, attracting the attention of star-struck groupies. Their sweat was even considered to be a prized aphrodisiac amongst the city’s most discerning libertines.

Who were the gladiators?

Ancient Mosaic of Gladiators in Battle, Villa Borghese

Ancient Mosaic of Gladiators in Battle, Villa Borghese

Despite their fame and popular adulation, gladiators were way down the social pecking order. Most were slaves or serious criminals who had parlayed their death sentences into a life in the arena. Others were prisoners of war from the conquered provinces, forced to become professional fighters in exchange for their lives.

Some, however, were willing participants eager for fame; as the games increased in popularity plenty of free citizens signed up for their shot at the big time. Retired soldiers, ex-cons, and even some upper-class men were recorded to have entered the arena in search of their 15 minutes of fame. The stakes were high – prize money for successful gladiators was extremely generous, and in one instance the emperor Tiberius tried to tempt his favourite retired gladiators back into the arena with a massive cash bonus of 100,000 sesterces each.

Being a gladiator wasn’t all a bed of roses though: they were rigorously segregated from polite society, and were incarcerated when not training or fighting. They retained an aura of dishonour about them even in death, interred far from their contemporaries in special graveyards of their own. The gladiators often organised into proto trade-unions called ‘collegia,’ which ensured their respectful burial and provided for the wellbeing of the families of fallen comrades. On other occasions gladiators paid for the funerals of the brothers in arms out of their own pockets.

Gladiators hailed from all over the Roman empire, and the gladiator schools in which they lived were extremely diverse multi-ethnic places. Spaniards rubbed shoulders with men from the Middle-East, North Africa and Eastern Europe. Women were also recorded to have fought as gladiators, although it seems that in the highly macho and misogynist society of Ancient Rome they were prized mainly for their novelty value, and were often required to fight topless. The demented emperor Domitian reputedly enjoyed watching female gladiators fight alongside dwarves.

How did the gladiators train?

The Ludus Magnus, ancient Rome's main gladiator school

The Ludus Magnus, ancient Rome's main gladiator school

No different to the top athletes of today, gladiators were highly trained professionals. They lived in the Spartan surroundings of gladiator schools; one, the Ludus Magnus, enjoyed a direct connection to the Colosseum itself via underground tunnels. Here they honed their art under the watchful eye of their coach, or lanista, who rented his charges out to games across the empire for a price.

Gladiators were the absolute property of their lanista, who could treat them as he pleased. Free-men who choose to join the gladiatorial ranks were also bound to accept whatever treatment their trainer meted out. They signed contracts which set out the conditions of their commitment, including the amount they were to be paid, the length of time they were obligated for, and the buy-out clause in case the thrill of risking their lives began to pale.

The public demanded entertaining spectacles, and in order to bring them up to the required standard their training regimes were brutal affairs that instilled iron-clad discipline in the gladiators. As the fights were more deadly ballet than chaotic free-for-all, training was methodical and involved learning specific moves just like a dancer might. The weapons they used to practice with were wooden, to stop them from killing each other or revolting against their masters, and weighed twice as much as the swords they would use in combat, as did their shields.

What did the gladiators eat?

A chunky looking gladiator from a mosaic in the Villa Borghese

A chunky looking gladiator from a mosaic in the Villa Borghese

Contrary to representations of extremely toned warriors like Russell Crowe’s incredibly buff Maximus in Gladiator, it seems gladiators were generally on the chunky side, and gorged on simple carbs to maintain a good layer of fat over their well-developed muscles. Gladiators were often called hordearii, or barley-eaters, and this cheap but nourishing staple was the cornerstone of their diets, often mixed into a porridge with beans.

There was a practical reason for this, too – ample stocks of subcutaneous fat helped to protect them from superficial wounds, meaning they could often fight on carrying non-fatal injuries.

To make up for the calcium deficiency their diets otherwise courted, gladiators were believed to have drunk fairly horrifying concoctions of plant and bone ash.

How Did the Fights Unfold?

Detail from a Gladiator's tomb, Photo by Carole Raddato via Wikimedia , CC BY-SA 2.0

Detail from a Gladiator's tomb, Photo by Carole Raddato via Wikimedia , CC BY-SA 2.0

Gladiatorial bouts were highly regimented and unfolded according to established protocols. They were frequently overseen by a referee known as a summa rudis, often himself a retired gladiator who intimately knew the ins-and-outs of the profession. Just like boxing referees today, they separated the gladiators if they were contravening the rules, and could order timeouts or stop the contest entirely. Usually the fights were single-combat and lasted for 10-15 exhausting minutes; as many as 13 combats could take place over the course of a single busy day at the arena.

The gladiators often dressed as barbarians, recalling the glorious victories of the Roman legions against them, and came in many different classes. Fights usually pitted contrasting kinds of gladiators against each other with similar experience and ability. Lightly armoured and agile warriors carrying nets and tridents might be matched against slow-moving gladiators wearing heavy armour and carrying massive two-handed swords, for example, the variety providing for an exciting spectacle.

Were Gladiator Fights to the Death?

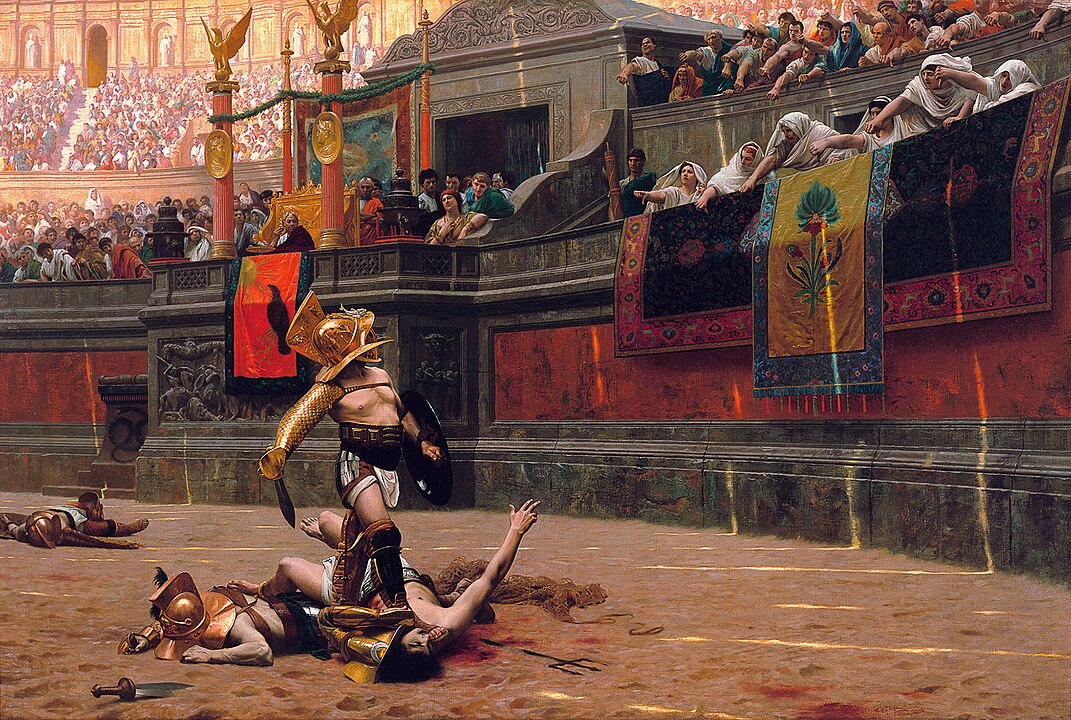

Gérôme, Pollice Verso, 1872

Gérôme, Pollice Verso, 1872

Not always. Fights lasted until one combatant was killed or ceded defeat, and were sometimes battles to the death, or sine missione. More often both fighters would leave alive, however, especially if they fought courageously. Gladiators were expensive commodities in which their trainers had invested thousands of hours of training and massive amounts of resources, and they were loathe see them killed unnecessarily.

In the contracts signed between the lanistae and the editor in charge of the games, heavy compensation was stipulated for gladiators killed carrying out their profession – this was often as much as fifty times the cost of the gladiator’s rental price for the games.

When a gladiator knew the jig was up, he could throw himself to the mercy of the crowds by falling to his knees and raising a finger towards the emperor in a bid for mercy. The emperor made his decision with a thumb-based gesture known as the ‘pollice verso’ – this meant a ‘turned thumb,’ and scholars don’t know if this was the thumbs-up/thumbs down gesture common in popular culture, or another sign entirely.

Protocol dictated that he would be swayed by the desires of the crowd, and prudent emperors were usually alive to the will of the people. Popular fighters were often spared even in defeat –after all, the games were thrown in a bid to keep the city’s population happy. Bucking the trend was the emperor Caligula, who was notorious for his unwillingness to show mercy to the vanquished: condemning popular heroes did little for his popularity with the masses.

What happened to the winners and the losers in the Colosseum?

Ancient Mosaic of a Gladiator battling a Wild Animal, Villa Borghese

Ancient Mosaic of a Gladiator battling a Wild Animal, Villa Borghese

But what happened to the gladiators when the bouts were over? To the winner went the spoils: a cash prize, a palm of victory, and a laurel wreath if the display in the arena was especially impressive. He then left through the winner’s gate, the Porta Triumphalis. A gladiator could also win his freedom with sustained excellence in the arena, and if the Emperor willed it he was given a wooden sword called a rudis in recognition of his achievement.

If the judgement of the emperor was that the vanquished warrior should die, the losing gladiator had to kneel and take hold of the victor’s leg as a sword was driven into his neck. Romans had a very theatrical method of ensuring that the condemned loser really was dead. Two attendants dressed in mythological garb made their way onto the sand of the arena: one was dressed as Charon, the ferryman who brought souls to the afterlife, and the other as Mercury, messenger to the gods.

Mercury carried a red hot piece of metal with which he poked the vanquished – if there was any sign of life, Charon took up the slack and staved his head in with the giant mace he carried. The corpses were then taken from the amphitheatre through the Porta Libitinaria, a gate dedicated to the Roman goddess Libitina who presided over funereal rites – this was the one way out of the Colosseum that no gladiator wished to take. Their bodies were stripped of clothing, armour and weapons in the nearby spoliarium, to be handed over to the newest recruits to the world’s deadliest game.

We hoped you enjoyed this primer to the gladiators who risked all for the entertainment of the bloodthirsty denizens of ancient Rome. If you want to learn more about the fascinating world of the ancient games in the spectacular surrounds of the Colosseum, be sure to check out our Colosseum tours!

MORE GREAT CONTENT FROM THE BLOG:

- How to Visit the Colosseum in 2025

- A History of the Colosseum

- Did the Colosseum Have a Roof?

- 5 Fascinating Facts About the Colosseum's Arena Floor

- The Colosseum Underground: The Deadliest Show on Earth

- Wild Animals in the Colosseum

- The Best New Tours of Italy in 2025

- Where to Stay in Rome in 2025: Areas and Hotels Guide