Time is like a river made up of the events which happen, and a violent stream; for as soon as a thing has been seen, it is carried away, and another comes in its place, and this will be carried away too.

- Marcus Aurelius

Time, to misquote a phrase, moves in mysterious ways. Marcus Aurelius ushered in two millennia of justifiable cliché by likening it to some great cosmic river, sweeping all before it on its long and inevitable course through the ages. But like a river too it eddies and flows, sometimes seeming to rush along at breakneck speed, at others slowing to an interminable crawl. Since the dawn of civilization mankind has sought out ways to bring order to its chaos, hoping to assert some kind of dominion over its fleeting and temperamental passage.

And thus was born the tyranny of the clock, ruthlessly dividing our days into regular and predictable intervals. With the invention of rigid time, inflexible and unforgiving, the entire institution of the modern world became possible. Disorder would recede with every tick of the well-calibrated timepiece - working hours could be set, and wages fixed. No longer would our days be determined by the constantly shifting course of the sun, as it was for the hunter-gatherers and peasants of our distant collective history.

The fickle changing of the seasons would now have to bow down to the will of humanity, a seismic shift in the age-old power relations between man and universe. But time, as it is measured by clocks and hours, is arguably testament more to the ingenuity of mankind than the messy reality of lived experience; it has yet to ensnare the entire world in its thrall.

I am standing in the massive shadow of the ancient horse-tamers, the Dioscuri,on the peak of Rome’s Quirinal Hill. The still-powerful sun of the legendary Roman Ottobrata (a period of typically balmy autumnal weather that makes this month the best to visit Rome) beats down on impossibly overdressed soldiers going through the motions of outmoded military ritual, their obsolete swords gleaming in the light.

My watch reads 2.30, and I have been waiting half an hour. A vaguely apologetic message outlines the reasons for my companion’s delay – the traffic, a trade-union demonstration beating pots and pans as they make their way to San Giovanni, cosmic forces badly aligned – but I am neither surprised nor annoyed. For as any new arrival to the Eternal City will soon learn, be they tourist or transplant, time here is fluid - more of a general suggestion than a binding summons. It turns out that this, like many of Rome’s most eccentric customs and institutions, has ample historical precedent. For Rome, you see, has been operating on its own time for millennia, a time as mutable and capricious as the city itself.

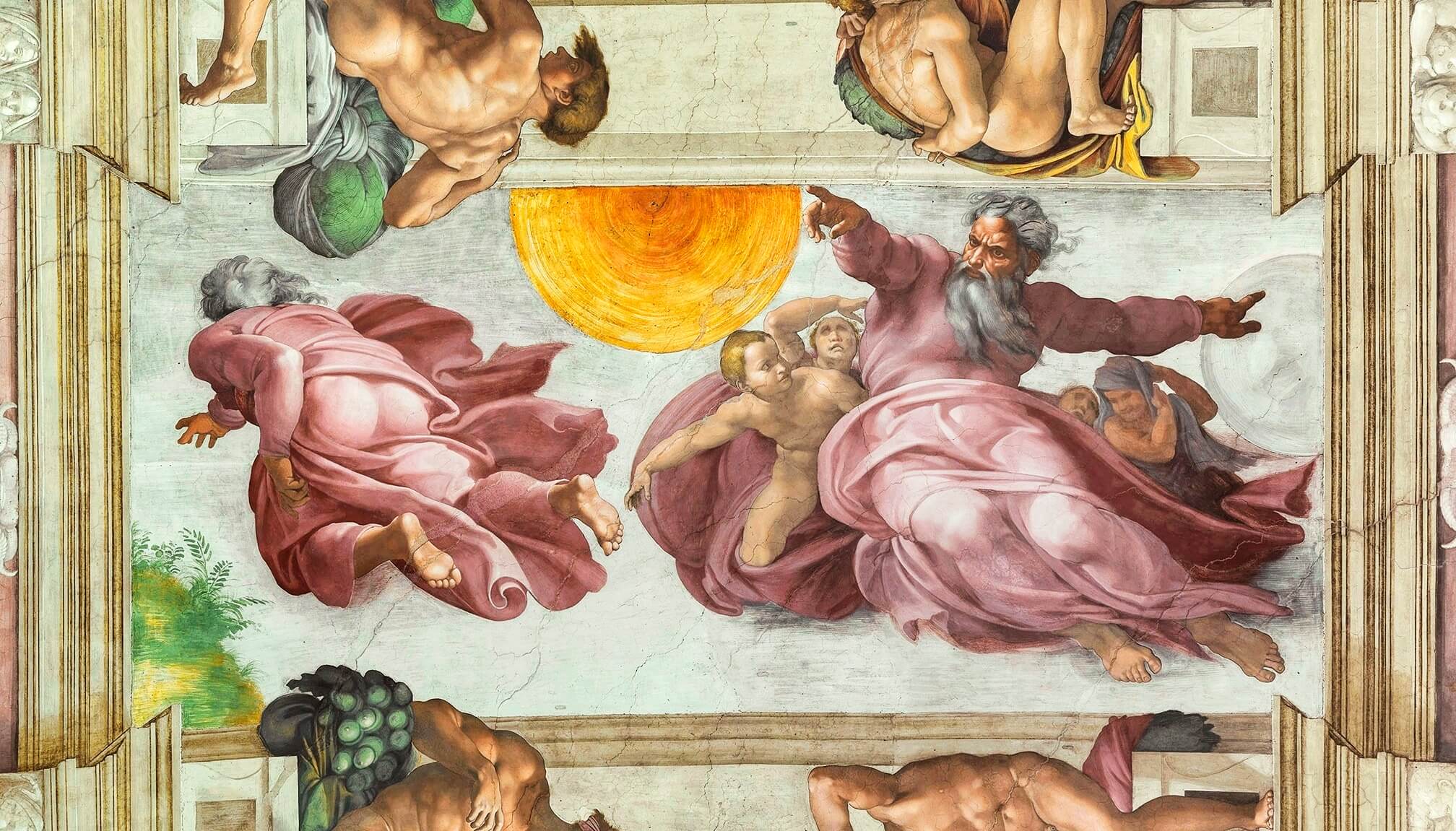

The most obvious and primitive division of our experience of time is of course the binary of light and dark, day and night. Echoing God’s own separation of those elemental forces (immortalised so memorably in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling), man’s first attempts to bring abstract structure to the flow of lived experience relied on this eternal constant; and so the passage of the days would change with the rhythms of the seasons.

Ancient sundials measured the path of the sun across the sky, but as they lay impotent at night, time existed only during the hours of daylight. The arc of the day was divided into twelve hours, but as the length of time between sunrise and sunset varied according to the season, the length of an hour too, varied - in antiquity an hour might last 75 modern minutes in summer and only 45 in winter.

With the advent of water-clocks, and finally clockwork in the middle-ages, darkness too was colonised by the divisions of man, and the structure of the day as we know it was born. Each day 24 equal hours ticked measurably by, regulated by the fixed points of midday and midnight, and so heedless of the changing seasons. Nature had been conquered, forced into a temporal straitjacket, and time had become a valuable, measurable and constant commodity - in major metropolises like London, entrepreneurs would make a small fortune by rushing from the Greenwich Observatory every morning with the latest, most accurate time, allowing the city’s movers and shakers to calibrate their watches and get on with the grand business of the day.

But in Rome, and much of the Italian peninsula besides, things worked a little differently. Here people remained happy to bend to the will of the sun, cut adrift from the uniformity and what many saw as the false objectivity of an unchanging, measurable time that was closing in from all sides around it. The ore francese or ore oltremontana (literally ‘beyond-the-mountain time’), as the system of timekeeping that we use today was known in Italy, stopped at the Alps.

In Rome, the method of timekeeping adopted instead was known as the Ore Italiche. Like the system that we know and use today, the ore italiche divided the day into 24 hours. The beginning of each day, or set of 24, began however at sunset, coinciding with the sounding of the Ave Maria on church bells. This obviously meant that each day also ended at dusk, making it simple to immediately determine how much daylight was left on any given day - if the clocks showed 23, then you knew you had an hour left, and so on and so forth.

The problem with the system, of course, was that it was intrinsically local and contingent. As the passage of the sun across the sky changed according to both the seasons and geographic location, the clocks also had to change constantly to ensure that the 24th hour coincided with the changing sunset. Midday, or the time of day that falls exactly midway between sunrise and sunset, was also a moveable feast - it might be at the 19th hour in winter and the 16th in summer. What was worse, the time would vary depending on which town or city you happened to be in.

The great German writer JW Goethe eloquently describes the somewhat bewildering system of timekeeping he encountered on his journeys in Italy in a passage from his late 18th-century travelogue Travels in Italy:

When night sets in…twenty four hours have passed and a new count begins, the bells ring, the rosary is recited, and the maid who enters the chamber with a lighted lamp bids us ‘felicissima notte.’ This moment changes with every season, and man, who in Italy lives a truer form of life, cannot go wrong because all of life’s enjoyments are regulated not by the nominal hour, but by the time of day. If they were forced to use a German clock they would be perplexed, because the system they use is so intimately connected with the environment in which they live.

But whilst the ore italiche had an undoubtedly romantic quality for those jaded by onrushing modernity, in an increasingly mobile world where travel was becoming the norm the system was a recipe for havoc.

Amazingly, this system remained in place in Rome and the Papal States well into the 1800s. To arrive in Rome was literally to arrive in another time. And so if you bought a clock in the city in the early 19th century, it came complete with a chart informing the owner as to how it needed to be recalibrated every two weeks to account for the lengthening and shortening of the days.

When Napoleon annexed the city in 1798, he did his best to put a stop to all that. To the apparently rational mind of a post-revolutionary Frenchman devoted to civic reform, such a backward custom couldn’t be allowed to continue. Clocks were changed, and the ore francese were instituted across the peninsula. The imposition of the new time led to much discontent, with many writers recounting the mass confusion of peasants not knowing when to go to market, and shepherds not knowing when to bring in their sheep.

But it would take more than the edicts of a dictatorial Corsican to drag Rome kicking and screaming into the modern world. Napoleon’s reign didn’t last long in the Eternal City, and the practice of the ore italiche continued for decades after his retreat. According to one somewhat bemused editorial in an American newspaper midway through the 19th century,

The Italians follow a mode of computing time different from that which is in use in any other part of Europe, and which although convenient enough for some purposes, is so much at variance with the true going of clocks, and with the practice of other nations, that it seems likely to be abandoned at no very remote period.

The editor was correct, and the ore italiche finally fell out of fashion not long thereafter. But although the city’s clocks may now reluctantly accord with their counterparts around the globe, it seems that the citizenry have felt no such obligation to follow suit.

Rome still moves at its own pace.

Through Eternity Tours offer award-winning, expert led itineraries in the Eternal City. From the jaw-dropping highlights of the Vatican Museums and the Colosseum to off-the-beaten-path gems that only locals know, join our small-group and private tours of Rome to discover the Eternal City at its best.