Easily one of the world’s finest museums, artistic masterpieces and cultural artefacts from every corner of the globe pile up on one another in the seemingly endless series of galleries and halls that constitute the British Museum. From Egyptian mummies to Aztec talismans, from towering Babylonian sculptures to intricate medieval chess boards and everything in between, the collection of London’s premier cultural institution offers a crash course in world civilisations and history like no other. But amongst the must-see masterpieces, one collection of objects stands out as being more spectacular, more important and more controversial than all the rest.

Known variously as the Elgin marbles or the Parthenon marbles, the series of sculptural reliefs depicting twisting conflicts between humans and mythological creatures, elaborate ancient processions, stunningly realistic horses and elegant gods have captivated visitors to the British Museum for centuries - and remain amongst the institution’s most popular attractions. But what exactly are these marble sculptures, and what are they doing in the British Museum? Read our Q and A to find out more!

What are the Elgin marbles, and where are they from?

Long lauded as embodying the uniquely refined aesthetic sensibility of one of antiquity’s most advanced civilisations, the sculptures originally formed part of the Parthenon, the most important building in ancient Greece. Even today the Parthenon remains the most visible and impressive building on the sacred Acropolis of Athens. The temple was built between 447 and 434 BC, when Athens was enjoying a Golden Age after the successful repulsion of an invading Persian army at the conclusion of the Greco-Persian wars.

Decades earlier, the iconic hilltop refuge had been desecrated in 480 BC by Persian forces under the command of Xerxes I in the wake of the brutal battle of Thermopylae. To honour the ultimate victory of the allied Greek states in finally repelling the Persian war machine, Athenian authorities under the magnetic general and leader Pericles decided to erect a magnificent temple on the renewed Acropolis that would celebrate the democratic values and resilience of the city-state.

Dedicated to the patron deity of Athens, the goddess of war and wisdom Athena, the jaw-dropping temple was decorated all over with painted sculptures honouring both the goddess and the military and social achievements of the city. Amongst the surviving remnants of these fabulous decorations are a sculpted metopes, or rectangular marble blocks, located above the temple's Doric colonnade, the continuous frieze that ran for fully 160 metres around the Parthenon’s inner chamber, or naos, as well as the sculptures that decorated the triangular pediments surmounting each of the temple’s facades.

What subject do the Parthenon metopes depict?

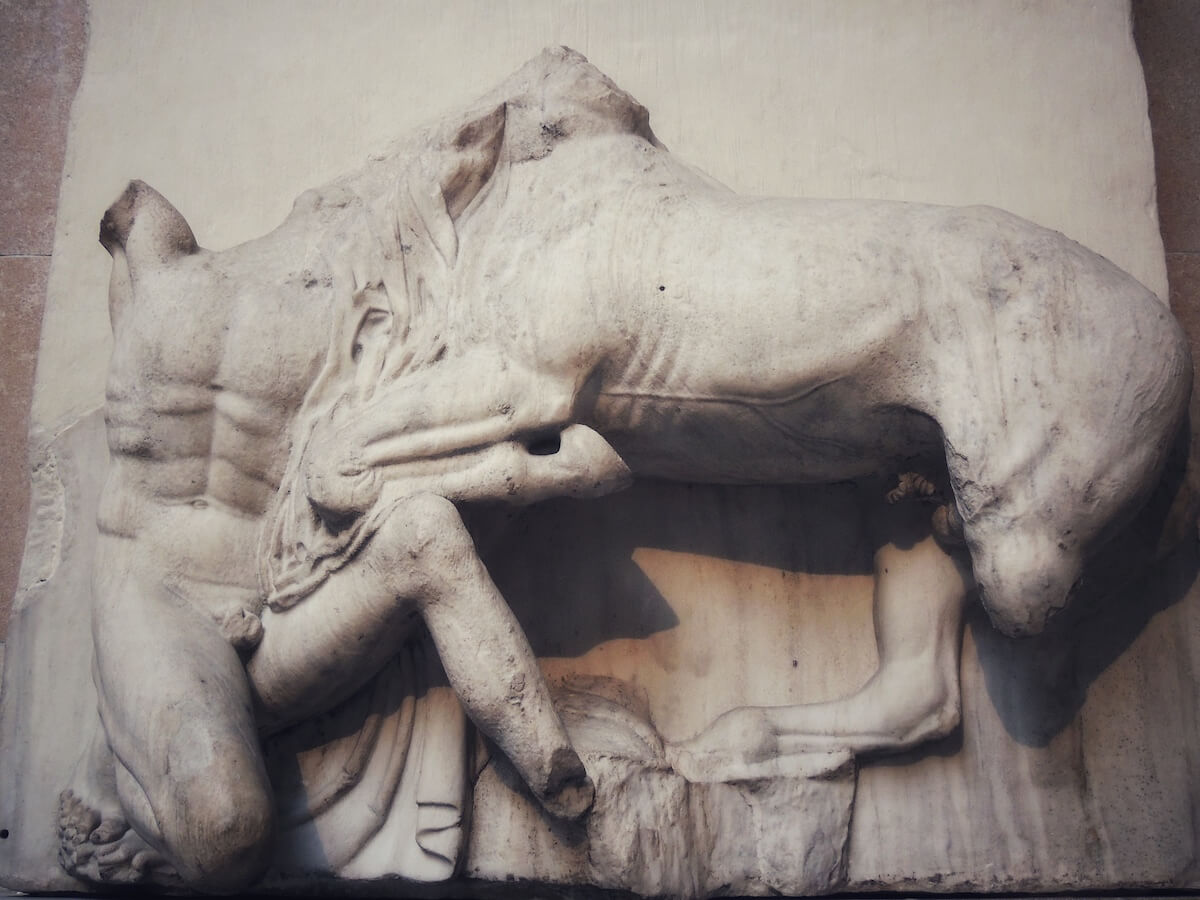

The marble sculptures of the metopes typically each depict two figures in their representational fields, and portray scenes of warfare. The metopes can be divided into four categories corresponding to four different mythological conflicts, depending on which side of the temple they were originally located.

The sculptures on the Parthenon’s western side depicted scenes from the Amazonomachy - the mythical battle between Athens and the Amazonians. The east side, meanwhile, was reserved for the Gigantomachy - the war between the Greek gods of Mount Olympus and the Giants. To the south we have the Centauromachy, a battle between the horse-human hybrid Centaurs and the Lapiths, a mountainous people from Greece. On the Partheonon’s northern facade, finally is a conflict that was very dear to Athenian hearts - the Trojan war.

The subtext of the narratives chosen for the Parthenon metopes was clear - just as the mythical Greek peoples of legend had triumphed over various tribes of monstrous foes or implacable enemies, so too would the Athenians, blessed with their advanced faculties of reason, successfully defend their patrimony over even the fiercest of rival civilisations.

The British Museum houses fifteen metopes from the Centauromachy cycle, and the meticulous depictions of the centaurs’ unique physiognomies is utterly spellbinding.

What subjects are depicted on the Parthenon frieze?

In contrast to the bloody deeds of derring-do depicted on the metopes, the Parthenon frieze instead gives us an inside peek into the social and cultural life of ancient Athens. Unfolding in a continuous narrative, the frieze depicts a magnificent procession of the Athenian citizenry to the Acropolis, an event that took place each year in honour of the city’s patron deity Athena.

The frieze shows the Athenians bringing gifts and sacrifices in honour of the goddess, including offerings of cows and sheep, honey and water. Look out too for the priestesses responsible for tending to Athena’s cult carrying the objects they will use in the sacrifices - incense burners and wine jars, knives and jugs.

A large portion of the frieze is also given over to the depiction of the troops of the successful Athenian army carrying trophies of their military triumphs. Horsemen wrangle with their steeds, chariots thunder serenely along, and knights brandish weapons on their way to the hilltop temple.

What subjects are depicted in Parthenon pediment sculptures?

The pediments (that is, the triangular areas surmounting the porticos on each facade of the building) of the Parthenon were decorated with dozens of massive statues portraying various ancient Greek gods engaged in dynamic action. The pediments were badly damaged over the course of the centuries, making hypothetical reconstructions of their exact subject matter impossible. Nonetheless, the elegant physiques of the surviving gods are widely regarded as archetypes of antique beauty. Busts of gods such as Athena, Poseidon, Amphitrite, Hermes and Iris all feature. Look out for the reclining figure of Dionysus, Greek god of wine-making and festivals - he is the only figure from the pediments to have retained his head.

Who carved the Parthenon sculptures?

The Parthenon sculptures have traditionally been ascribed to the ancient Greek sculptor Phidias, a close friend of Pericles who was renowned as one of antiquity’s finest artists. According to the Roman historian Plutarch, “the man who directed all the projects and was overseer for [Pericles] was Phidias... Almost everything was under his supervision, and, as we have said, he was in charge, owing to his friendship with Pericles, of all the other artists.”

But although Phidias played an important role in overseeing the works, he was far from alone: the entire sculptural project was completed in an extremely short time span, and required the skills and contributions of a vast team of artists. Indeed, stylistic analysis has revealed the contribution of various craftsmen to the project. Phidias was almost solely responsible for the massive cult statue of Athena that was located at the heart of the temple, however, regarded as one of the wonders of the ancient world.

How did the marbles end up in England?

During the early-modern period, Greece formed part of the vast Ottoman empire, which stretched from western Asia to South-Eastern Europe and North Africa. Over the centuries of occupied rule the venerable Athenian acropolis suffered innumerable damages, culminating in a disastrous event in 1687, during one of the innumerable wars waged between the Ottoman Turks and the maritime Republic of Venice - the empire’s most implacable European foe.

As Venetian forces advanced on the city, Turkish forces retreated to the Parthenon, which was being used as a gunpowder store. Artillery fire from the besieging Venetian army scored a direct hit on the munitions dump, damaging the ancient temple and sending marble fragments flying. Much of the marble frieze was knocked to the ground, leaving it vulnerable to looters and treasure hunters.

Fast forward a little more than a century, and the Earl of Elgin has been appointed British ambassador to the post of ambassador to Turkish-controlled Greece. Elgin hatched a plan to have a squadron of artists take casts and make drawings of the Parthenon sculptures. The work soon proved to be more acquisitive than documentary in nature however, and Elgin’s agents wasted little time extracting much of the remaining sculptures and packing them off to Britain, where they arrived in multiple shipments over the coming years, culminating in 1812. In total about half of the Parthenon frieze was pilfered by Elgin, along with numerous metopes and sculptures from the pediments, as well as other artefacts from the Acropolis site.

Due to a ruinous divorce settlement, Elgin’s plans to make the marble sculptures from the Parthenon the centrepiece of a new private museum dedicated to the splendours of antiquity fell through, and he was left with no choice but to sell the statues to the British State. The government agreed to the sale in 1816, and the marbles were put on display in the British Museum soon thereafter, where they remain to this day.

Did Lord Elgin take the Parthenon marbles legally?

It depends on who you ask. Elgin claimed to have received official written permission from the Turkish authorities to remove the sculptures, although many scholars dispute that the documents in question granted him such sweeping powers. The legality of the expropriation was a subject of debate at the time; a special session of the British Parliament ultimately coming down on the side of Elgin, but many prominent voices from the world of public discourse furiously disagreed. The Romantic poet and lifelong Hellenophile Lord Byron was perehaps the most eloquent voice of protest, writing that

‘Dull is the eye that will not weep to see

Thy walls defaced, thy mouldering shrines removed

By British hands, which it had best behoved

To guard those relics ne'er to be restored.’

What’s the controversy today about the Parthenon marbles?

Over 500 years of Ottoman rule over Greece ended soon after the final consignment of the Elgin marbles had been shipped off to northern climes, with Greece declaring victory after a bloody 8-year long war of independence in 1829. It wasn’t long before the government of the newly independent state requested the return of the Parthenon marbles in a communique to the British government in 1835. Their request went unanswered, and has been repeated multiple times since. In 1983 the Greek government took the issue to the UN, arguing that the return of the nation’s cultural patrimony is a question of natural justice, and that any agreement between the officials of an occupying Ottoman empire and a British nobleman would in any case be invalid today.

The British position is that the marbles were acquired legally by Elgin, and as the British Museum is one of the world’s most visited museums the priceless artefacts are accessible to as wide an audience as possible in their current home. The museum and British government have also raised doubts as to the ability of the Greek authorities to adequately provide for the sculptures’ conservation, although this talking point was largely rendered null and void after the completion of a dedicated museum at the Athens Acropolis, which opened in 2009 and is home to the remainder of the Parthenon marbles.

Although public support appears to be with returning the marbles to Greece, British authorities continue to insist that they have their natural forever home in the British Museum. UNESCO has recently called on the United Kingdom to engage in meaningful dialogue with their Greek counterparts, which they have yet to do. The dispute, in other words, is ongoing.

Where can I see the Parthenon marbles today?

Around half of the surviving Parthenon sculptures are now housed in the British Museum, including 15 of the metopes depicting the battle of the Lapiths and the Centaurs, 75 metres of the Parthenon frieze, and 21 figures from the east and west pediments of the temple. The Elgin marbles are located in a large dedicated exhibition space in the British Museum called the Duveen Gallery, where they were moved in 1939 thanks to a bequest by the English art dealer and aristocrat Sir Joseph Duveen.

Whatever the political rights and wrongs of their current whereabouts, the Parthenon marbles constitute the greatest surviving cache of ancient Greek classical sculpture to survive to the present day, and are key to our understanding of the evolution of art in antiquity. No visit to London would be complete without an afternoon spent uncovering their secrets.

Visit the British Museum’s extensive collection of Greek artefacts for yourself on a self-guided visit, or book a private tour of the British Museum with an expert guide from Through Eternity Tours to get the fascinating full story of these masterpieces of ancient art!