Home to Michelangelo’s David, the Accademia Gallery in Florence is an absolute must-see when visiting the city of the Medici. But whilst we are sure you have got the Accademia on your itinerary during your trip to Florence, have you wondered what else there is to see in the museum beyond the extraordinary David?

From wacky medieval paintings to Renaissance masterpieces, priceless musical instruments and, of course, some truly extraordinary artworks by Michelangelo, here is what you need to see when visiting the Accademia Gallery in Florence.

Michelangelo, David, 1504

In the dying years of the 15th century, an enormous marble block had lain abandoned in the courtyard of Florence’s cathedral for 30 years. The stone was flawed and damaged, frustrating all attempts to transform it from base material into a work of art.

Numerous were the artists who had tried and failed, tossing their chisels in despair at the impossibility of the task. Locals knew it only as ‘the giant.’

That all changed in 1501, when Michelangelo returned from Rome in order to fashion the block into what would become the most famous sculpture of Renaissance Italy.

Its flaws were no match for Michelangelo’s brilliance, and the anonymous marble giant finally received an identity: the heroic shepherd-boy David, who defeated the mighty Goliath and saved his people.

David’s perfect proportions, amazingly realistic anatomy and noble features meant that the work soon provoked universal acclaim amongst Michelangelo’s contemporaries.

Plans to place the David high up on the facade of the Duomo were scrapped, with city authorities instead choosing to give it pride of place in front of the Palazzo Vecchio. There it stood for over 350 years, before being moved to the Accademia in 1873.

A face-to-face meeting with the giant of Florence remains one of the world’s most inspiring artistic experiences - experience it for yourself on our Best of Florence tour.

Michelangelo, Prisoners, c1520-34

David might be the Accademia’s main draw card, but the museum is also home to other masterpieces by Michelangelo. These are the so-called Prisoners or Awakening Slaves, a series of unfinished sculptures that the artist intended to display on the tomb of Pope Julius II in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, one of the biggest commissions of Michelangelo’s career.

Michelangelo was forced to pause the project when the capricious Julius ordered him to fresco the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel instead, and the tomb was never completed as Michelangelo intended.

The four struggling figures on display in the Accademia Gallery were supposed to hold up columns on Julius’ tomb, but as the project was shelved Michelangelo never finished them.

That’s actually no bad thing, because in their incomplete state they demonstrate a key aspect of Michelangelo’s artistic philosophy. Michelangelo believed that the forms of the sculptures he created already existed deep within the blocks of stone he used - it was his task simply to liberate them from their marble prisons.

And so with the Prisoners you can almost literally see the figures emerging as if by magic from the marble; the fact that they haven’t made it out completely only adds to their poetic power.

Michelangelo, Saint Matthew, 1506

photo credit: wikimedia commons, CC license

In 1503 Michelangelo received an important commission to create statues of the 12 apostles for the facade of Florence Cathedral. By now in extremely high demand from powerful patrons, however, Michelangelo only began one sculpture in the series before being summoned to Rome to serve at the court of Pope Julius II.

The work is unfinished, but the figure of Saint Matthew is nonetheless interesting for the sense of tension created by the apostle’s head and body twisting in different directions. This is a good example of the Renaissance concept of the contrapposto, and was perhaps also inspired by the example of the ancient Laocoon statue, discovered in Rome earlier that year and now on display in the Vatican Museums.

By now you’re starting to get the idea that Michelangelo didn’t finish many of the sculptures he started. In fact, amongst Michelangelo scholars there is even a phrase for describing this phenomenon: the non-finito, or unfinished. Far from being a failing, however, seeing Michelangelo’s works in varying degrees of completion help us to understand how for the artist the creation of art was an ongoing process that could never truly be completed.

Giambologna, Abduction of a Sabine Woman, c1580

photo credit: wikimedia commons, CC license

photo credit: wikimedia commons, CC license

Giambologna was arguably the finest sculptor of the late-Renaissance style known as Mannerism, in which artists sought to create highly complex compositions that showed off their technical skill. His masterpiece is the massive marble portrayal of the dramatic Abduction of a Sabine Woman in Florence’s Loggia dei Lanzi. In this legendary event from the early history of Rome, the upstart city’s soldiers abducted the womenfolk of the neighbouring Sabine tribe in order to make them their wives.

But although the twisting, corkscrewing sculpture does picture a muscular young man carrying a woman away in his arms as another figure looks on in dismay, Giambologna actually made his sculpture without a subject matter in mind: he was much more interested in the formal possibilities of the statue, and the work only took on its current title when it was suggested by the learned humanist scholar Vincenzo Borghini after it was already complete!

The sculpture you can see in the Accademia Gallery is a full-size clay preparatory model, and offers fascinating insights into Giambologna’s working practice - walk all around the model to get a sense of how the sculptor revolutionised the art form by creating a sculpture that could be appreciated from any angle.

To see the completed marble statue in the Loggia dei Lanzi, book our Day in Florence tour.

Perugino, Vallambrosa Altarpiece, 1500

Surrounding Giambologna’s model on the walls of the Hall of the Colossus are a number of works by Renaissance masters. Amongst them is Perugino’s glittering Assumption of the Virgin, also known as the Vallombrosa Altarpiece, painted for the Abbey of the same name.

The three-layered composition features God the Father at the top of the panel surrounded by cherubs and angels; beneath, the figure of the Virgin Mary rises serenely upwards towards heaven in an almond-shaped mandorla, as music-making angels serenade her ascent.

In the bottom register, four saints - Bernard degli Uberti, John Gualbert (founder of Vallombrosa Abbey) Benedict and the Archangel Michael - gaze at the miracle.

The altarpiece is a great example of the serene and harmonious style of Perugino, which was also highly appreciated by the French General Napoleon: Le Petit Caporal pilfered the altarpiece in 1810 in the aftermath of his Italian invasion and had it carted off to Paris. Thankfully, it was returned to Florence a decade later.

Filippino Lippi, Deposition from the Cross, c1506

Next to the Vallambrosa Altarpiece is Filippino Lippi’s Deposition from the Cross, a dramatic Renaissance imagining of the moment that Christ was removed from the cross after his crucifixion.

The ladders being used to take Christ’s body down adds a powerful rhythmic quality to the composition typical of Renaissance aesthetic ideals. The Virgin Mary swoons at the foot of the cross the sight of her dead son, while Mary Magdalene kneels in pious prayer.

The Deposition from the Cross originally formed part of the larger Annunziata Polyptych, painted for the high altar of the Basilica dell’Annunziata in Florence. It would prove to be Lippi’s final work: in fact, the artist died in 1504 before the painting was complete, and the work was completed by Perugino, who painted the lower figures as well as the face of Christ.

Lo Scheggia, Cassone Adimari, c1450

Another magnificent work to look out for in the Sala del Colosso is the Cassone Adimari. A cassone was a kind of large chest typical of Renaissance Florence in which brides would transport their possessions to their new marital home. As objects of both functional importance and symbolic significance, cassoni were very important objects and were frequently elaborately decorated.

One of the painters best known in the Renaissance for decorating cassoni and other domestic objects (in fact, it is now believed that the Adimari work was actually a spalliera, or the headboard of a bed) was Giovanni di Ser Giovanni, known as Lo Scheggia. Lo Scheggia’s fame was eclipsed by that of his younger brother, the preternaturally talented Masaccio, but as we can see from the Adimari cassone, was a fine artist in his own right.

The painting depicts a scene from contemporary 15th-century Florence in fascinating detail. From the distinctive architecture of the Baptistery we know that we are in Piazza del Duomo, where a wedding celebration is going on. Trumpeters play fanfares as the marriage couple make their way beneath a large temporary awning.

The painting offers a wealth of details that provide incredible insight into life in Renaissance Florence: look out for the distinctive architecture of the houses and the stunning costumes worn by the participants.

Learn more about the secrets of Lo Scheggia's fascinating panel on a private tour of the Accademia Gallery.

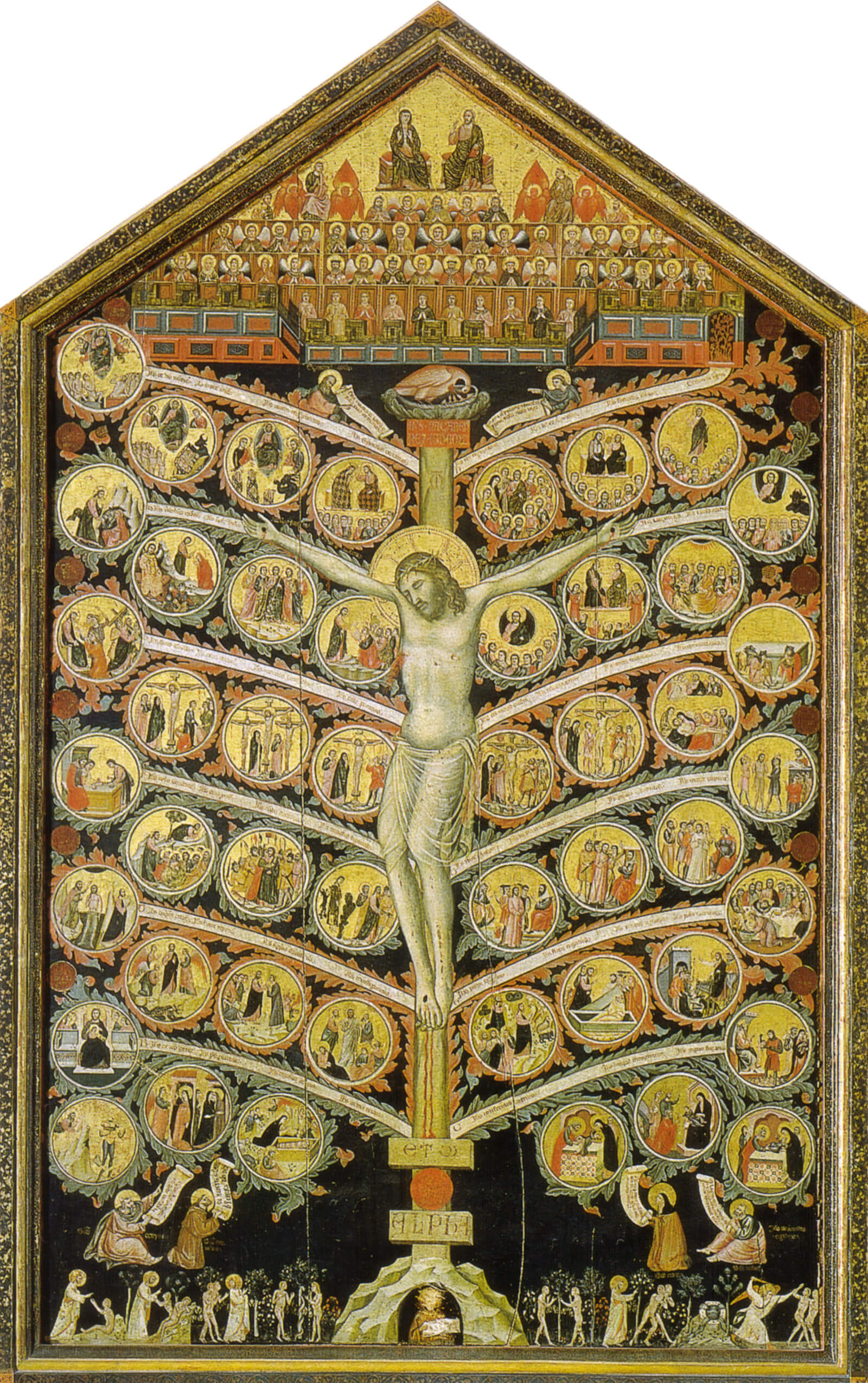

Pacino di Bonaguida, Tree of Life, c1305-10

The Accademia isn’t all about the Renaissance. In fact, one of the museum’s most fascinating artworks is this medieval painting depicting the very unusual subject matter of the Tree of Life.

Here we are far removed from the concerns that animated the artists of the Florentine Renaissance: instead of a realistic portrayal of the world that we see around us, Bonaguida’s panel is highly abstract and allusive. Ostensibly the painting depicts the Crucifixion of Christ, but a closer look reveals that the subject matter is a lot more complicated than it first appears.

6 branches spring from the cross on each side of Christ, transforming him into a kind of tree. 48 medallions hang from the branches like fruit, each containing a miniature scene from Christian teaching. At the very top of the tree Bonaguida has painted the paradise of Heaven - the final stop on the journey of life made possible by Christ’s sacrifice.

Inspired by the teachings of the Franciscan theologian Bonaventure, Bonaguida painted the Tree of Life for the Poor Clare order of nuns of the Monticelli convent in Florence around the year 1310. Its abstract subject and glittering details offer a fascinating insight into the mysterious world of Medieval spirituality.

Plaster Casts in the Gipsoteca Bartolini

photo credit: wikimedia commons, CC license

In an era before photographic reproduction, plaster casts of famous artworks formed an essential tool for the training and development of young artists. Giving them the opportunity to study and sketch important sculptures first hand, collections of casts were a common feature of the most important 19th-century art academies, and Florence’s Accademia was no exception.

The driving force behind the Accademia’s plaster cast collection was the 19th-century artist Lorenzo Bartolini. Bartolini was one of the Academy’s leading lights, and the beautiful Gipsoteca Bartolini recreates his studio space complete with hundreds of plaster casts that he made of his own works - from busts of important luminaries and fellow artists to full-scale recreations of important commissions.

The Gipsoteca Bartolini was reopened to the public in 2022 after an important restoration, and looks absolutely spectacular with its row after row of white plaster casts displayed alongside 19th-century paintings.

Hall of Musical Instruments

photo credit: wikimedia commons, CC license

There’s more to the Accademia in Florence than the visual arts. One of the more surprising aspects of the museum’s collection is the Sala degli Strumenti Musicali, opened in 2001 to showcase some truly spectacular examples of early-modern musical instruments.

Many of the pieces come from the collection of the Medici family, and include a delightfully crafted 17th-century cello made by the Baroque master Niccolò Amati, as well as three instruments crafted by Antonio Stradivari, widely regarded as the greatest musical instrument maker in history.

Also of interest is a room devoted to the development of the piano, which was invented by Bartolomeo Cristofori in 1720 - here you can see a spinet (an instrument somewhere between a small piano and a harpsichord) that Cristofori made for the Medici.

Planning a visit to Florence? Through Eternity offers a range of group tours in Florence as well as private itineraries that take you to the best sites in the city, including the Uffizi Gallery and Accademia.

MORE GREAT CONTENT FROM THE BLOG:

- How to Visit the Accademia Gallery

- Is a Tour of the Accademia Worth it?

- The Best Museums in Florence

- What to See in the Uffizi Gallery

- 7 Churches in Florence You Need to Visit

- Donatello's Penitent Magdalene in Florence